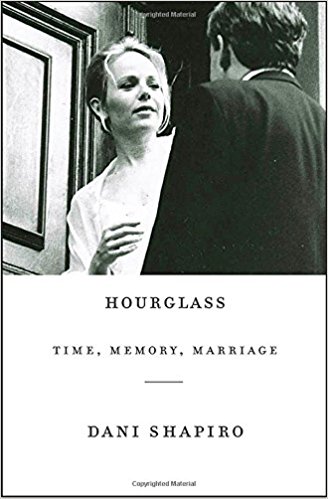

Dani Shapiro’s new memoir Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage is an investigation into what happens when two people promise to abandon their individual paths in life and go down the same one together. It asks what we lose and gain in making the choice to link our life to another’s. It looks, too, at the selves that fall away in the process—the individual traits we hide to meet a partner’s needs, as well as the past selves that slip aside, unbidden, as we age. These past iterations of us dissolve with the decades—and the decades in turn disappear in a blink.

Dani Shapiro’s new memoir Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage is an investigation into what happens when two people promise to abandon their individual paths in life and go down the same one together. It asks what we lose and gain in making the choice to link our life to another’s. It looks, too, at the selves that fall away in the process—the individual traits we hide to meet a partner’s needs, as well as the past selves that slip aside, unbidden, as we age. These past iterations of us dissolve with the decades—and the decades in turn disappear in a blink.

Shapiro offers beautiful meditations on the passage of time in her prose, telling the reader in one especially memorable section that “the decades that separate [the] young mother [she once was] from the middle-aged woman discovering them feel like the membrane of a giant floating bubble. A pinprick and [she’s] back there.”

At times ruminative and nakedly candid, the narrative succeeds at bringing the reader into Shapiro’s mind, marriage, and past. The reflective nature of the text is its strength and downfall at the same time. It asks us to examine the questions Shapiro asks herself, and this allows us to contemplate time, love, and conjoined fates with her. Like a real, human conversation—which is an art eroding as quickly as the framework of Shapiro’s woodpecker-ravaged home in rural Connecticut—the text’s pensive lines and white-space-laden structure allow the kind of insight only possible when a story has the space to breathe.

A passage such as “Oh child…the future you’re capable of imagining is already a thing of the past. Who did you think you would grow up to become? You could never have dreamt yourself up. Sit down. Let me tell you everything that’s happened. You can stop running now. You are alive in the woman who watches as you vanish” reveals a masterful collapsing of time, situating its unending forward motion within the framework of an omnipresent past.

Shapiro’s narrative stumbles in its lack of a central story. I enjoyed spending time in its pages, seeing from a perspective that as a never-married thirty-three-year-old I can only access indirectly; yet, I found myself wishing for a traditional through-line. What she gives us is more meandering. We weave through time with the author, learning that her now sixteen-year-old son almost died as an infant. We become privy to details about her prior marriages and the painstaking process of learning to stay in such a union. We learn, too, about the skins her husband M. has shed with time, that is, his “past lives” as a journalist in war-ravaged territories and his love of danger. In some of her most honest moments, Shapiro wonders if he had to stop being him in order to be with her. When M. is particularly enlivened by a brutal snowstorm, saying, “It’s like a war out there,” Shapiro admits bluntly, “I hate him.”

These raw admissions are what compel me to read, rather than a sense of story—because there really isn’t one. Shapiro herself admits this three-quarters of the way through the book: “Memoir freezes a moment like an insect trapped in amber. Me now, me then. This woman, that girl. It all keeps changing. And so: If retrospect is an illusion, then why not attempt to tell the story as I’m inside of it? Which is to say: before the story has become a story?”

At a previous time, she believed an event could only be told after the fact, a view she has since abandoned. She now believes that the “onrushing present” is the “only place from which the writer can tell the story.” This is intriguing, and I appreciate it from an aesthetic stance, but to this reader such a statement raises the question: What if Shapiro has simply run out of stories?

The present can be just as intriguing as the past. But we look to the writer to arrange its events just as she would’ve if they’d already reached their culmination. Shapiro’s book mostly eschews the notion of arc, offering reflection without the counterbalance of real narrative. It made me wrestle with the question of what gets to be a book.

I struggled, too, with the presentation of my state. As someone born and raised there, I could not help but think it was not my Connecticut present in its pages. A memoirist can only show us their life—but still, to read that Shapiro and her family “decamped for the wilds of Connecticut” shows only the most unidimensional stereotype of what is actually a complex place.

I was born, for example, in Bridgeport, a town that grapples with gang violence and sends its students home with backpacks full of snacks so children won’t go hungry over the weekend. For those children, and for me, Connecticut was far more than a bucolic place of respite or an escape from the city. I had no idea as a child that the notion of my state as a playground for the wealthy was based at all in reality. The income gap in the state is the starkest in the country, and Shapiro’s Connecticut may as well have been a world away. I spent my childhood in a suburb, but we did not own a yacht or go to private school. It’s hard to see the place I grew up dubbed the countryside when I know it to contain strata of diverse and complicated lived experiences.

I enjoyed this memoir for its thoughtful, skillful lines, for the sharpness of its insight about how we change as we move through life, and for the questions it made me ask, too: Who gets to tell stories? Who decides what narrative is? And just what do we see as reality?

__

Emily Heiden is pursuing a Ph.D. in literary nonfiction at the University of Cincinnati. She holds an MFA in nonfiction from George Mason University. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Long River Review, and Juked Magazine.