Here in New England, we had four nor’easters in March: Riley, Quinn, Skylar, and most recently Toby. My friend’s business trip to Boston coincided with Quinn. While I’d classify her as a conscientious, cautious, and well-planned traveler, she decided this time not to pack snow boots. They didn’t match her outfits. They were too big for her carry-on.

Here in New England, we had four nor’easters in March: Riley, Quinn, Skylar, and most recently Toby. My friend’s business trip to Boston coincided with Quinn. While I’d classify her as a conscientious, cautious, and well-planned traveler, she decided this time not to pack snow boots. They didn’t match her outfits. They were too big for her carry-on.

“You do have sidewalks…don’t you?” she asked.

Three days into her stay, she described to me how she forded a slushy black stream while crossing Commonwealth Avenue. Her feet were wet and cold, her shoes mucky. She was sorry.

Trust the New Englander. We abandon looking cute or even professional once snow starts to fall. The goal is simply to be clean, warm, and dry—and that’s not so easy. It means piling on everything that’s waterproof: a parka, boots, layers of scarves, and heavy gloves. If you show up at your cocktail party or business meeting dressed like an Arctic explorer, no one will think badly about you. No one will bat an eye or say anything…except maybe praise you for your sensibility.

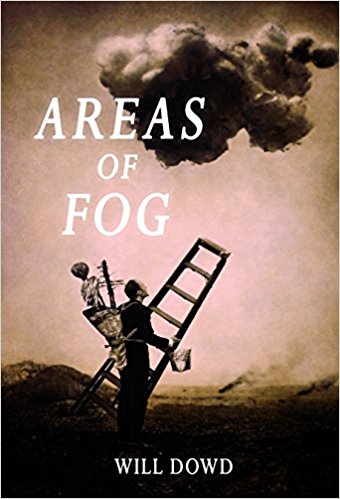

Author Will Dowd, a New Englander, knows all about nor’easters, mud season, and the slow, coy emergence of spring. In a collection of connected essays, Dowd muses about the region’s eclectic weather in Areas of Fog.

“All the weathermen of New England go mad eventually,” he writes in the opening. “After a few decades spent attempting to predict the unpredictable, they succumb to a kind of meteorological nihilism and wander out of the studio mid-broadcast, muttering to themselves, and can be seen a week later selling wilted roses on the side of the highway.”

Hmmm. I’ve seen these guys in the South End waving their limp roses.

In Dowd’s slim book, he traces a calendar year of New England weather. “It’s been a winter of naming,” he writes. “Every week the weather-industrial complex introduces and calculates a new buzzword for a weather phenomenon that has already existed (‘Bombogenesis’ is having its moment), while The Weather Channel has gone rogue and begun naming blizzards. They’re not even proceeding through the alphabet. It’s chaos.” (See above.)

Why? In part, it’s because Americans don’t have an extensive vocabulary when it comes to weather. Northern Native Americans may have fifty names for snow, but “we still have no name for the first labored swipe of windshield wipers over morning frost,” he writes. “We still have no name for the mist that rises off the shoulders of melting snowmen like their departing souls.” We have no name for those first optimistic rays of sun that sneak through the clouds after eleven days of fog and driving snow.

Dowd draws from anecdotes, letters, poetry, and quotes from various artists and writers who’ve lived in or, at least, visited New England. From Mark Twain, he shares this insight: “In the spring, I have counted one hundred and thirty-six different kinds of weather inside of four and twenty hours.” Twain observed this from his home in Connecticut, where he lived the last seventeen years of his life.

Dowd writes about flooding, particularly in MIT’s $300 million Strata Center, where the author typically eats his lunch. “A yellow and white aluminum scrapheap, it was designed by Frank Gehry to look like ‘a party of drunk robots got together to celebrate,’” he writes. Obviously, he’s not a fan of Gehry’s, and to him, the building looks more like a “cubist omelet.”

Gehry famously denied his building leaked. He stood in front of a crowd and shouted, “My name is Frank Gehry and my buildings don’t leak.” Nevertheless, Dowd “avoided brimming buckets and ducked under caution tape” on his way to the cafe.

It’s stories like that make this book a fun read—even for New Englanders, who you’d expect to be bored to tears in hearing about weather. Not. In spite of their groveling and complaining, they are truly weather obsessed, checking in with weather reporters all day long to hear the latest.

“Yet while they may be doomed to fail, we don’t mock our weathermen,” Dowd writes. “Even though we see them for what they are—oracles draped in sheep entrails—we don’t change the channel. We listen politely to their forecast. And then we talk about it.”

___

Debbie Hagan is book reviews editor for Brevity and author of Against the Tide (Hamilton Books, 2004). Her essays have appeared in Harvard Review, Hyperallergic, Pleiades, Superstition Review, Brain, Child, and elsewhere. She’s a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.