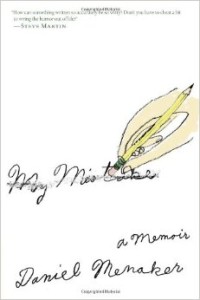

Perhaps it’s the ideal pairing of human characteristic and profession: the anxiety-ridden who becomes editor. In My Mistake, former New Yorker fiction editor and Random House’s executive editor-in-chief Daniel Menaker explores the life that led him to become one of the country’s most reputable editors. The book’s title is a sly reference to the editor’s plight, constantly combing for errors. Here an anxious mind comes in handy. Like Menaker, I work as a writer and editor and wrestle with anxiety. I, too, have found that the very fears that plague me evolve into superpowers when it comes to editing. The need to repeatedly review a draft for the tiniest error and the desire to bring a piece to perfection might not be healthy—or what some people might say is obsessive—in the end leads to better prose.

Perhaps it’s the ideal pairing of human characteristic and profession: the anxiety-ridden who becomes editor. In My Mistake, former New Yorker fiction editor and Random House’s executive editor-in-chief Daniel Menaker explores the life that led him to become one of the country’s most reputable editors. The book’s title is a sly reference to the editor’s plight, constantly combing for errors. Here an anxious mind comes in handy. Like Menaker, I work as a writer and editor and wrestle with anxiety. I, too, have found that the very fears that plague me evolve into superpowers when it comes to editing. The need to repeatedly review a draft for the tiniest error and the desire to bring a piece to perfection might not be healthy—or what some people might say is obsessive—in the end leads to better prose.

In some ways, Menaker credits his generalized anxiety disorder to his success at the New Yorker, where he began as a fact checker. “It’s no wonder that with Valium always on my person and the need to lose myself in something that would take my mind off this dread, I throw my energy into fact-checking so violently,” Menaker writes. Working furiously—he called himself a “demon Fact Checker”—calmed and focused him, and as a result of his efforts, he received in just a few years a sought-after promotion to copy editor.

His success at coping with his anxiety, aided by the many years of therapy, is revealed in his ability to now reflect on his life without editing out his “mistakes.” He looks upon them wryly and writes from the point of view of acceptance—mistakes and all. However, always the editor, he cannot refrain from pointing them out—often humorously. He writes of an incident involving formidable New Yorker editor Gardner Botsford at a party: “I go to remove what I think is a piece of thread from Mr. Botsford’s lapel. My mistake. I’m right—it is thread, red thread—but somebody deflects my hand, thank God, and tells me that that thread is the insignia of France’s Legion of Honor.”

Menaker is surrounded by true characters, not just at the New Yorker, but elsewhere in his life. He sometimes writes as if he’s only as interesting as the list of people he’s known, which includes famous and unfamiliar individuals. Menaker pays tribute to his Uncle Enge (“rhymes with mange”), a Marxist square dance caller who owned a camp in Massachusetts; William Maxwell, his elegant mentor at the New Yorker; and his older brother Mike, a father figure who died tragically young during a routine surgery to fix an injury for which Menaker himself felt responsible. At times, like a Dickens protagonist, Menaker allows this supporting cast to command the reader’s attention. But Menaker is such a good editor—and writer—that the subtlety of his style characterizes him more beautifully than if he had simply focused on himself.

If Menaker had not spent decades at the New Yorker, and could not illuminate the inner workings of that fascinating office, his memoir would still resonate. Yes, it is riveting reading about William Shawn’s peculiarities as the New Yorker’s long-standing editor (he abhors the words “gadget” and “teddy”), or what Truman Capote sounds like on the phone (“just tell him Twuman called”), or the Random House decision to keep the author of Primary Colors anonymous. (Menaker advocated for this outcome.) But Menaker’s writing is most striking in his brief frankness about his struggles: his secret feeling throughout his editorial career that he is a fraud; his guilt about his brother’s death; and his struggles with mental health.

Menaker’s literary career is the way into his writing. The details he includes about the behind-the-scenes life of the publishing world are incredibly compelling—and funny. But Menaker’s thoughtful, subtle prose about his life, including the many mistakes for which prompted this title, is the true meat of the story. As a man in his later years and in remission from cancer, he reflects honestly about his complex history with critical distance. And despite the vivaciousness of the many characters—people and publications alike—who grace this book, Menaker is the one worth knowing.

__

Emilie Haertsch works as a writer and editor in the Philadelphia region. She received an MFA in creative nonfiction from Goucher College, and her work has appeared on Huffington Post, Apiary, Raleigh Quarterly, and WBUR Public Radio.