I worry when a person announces proudly that they’ve done a serious revision of something they wrote. Usually, that means they’ve proofread it with style sheet in hand, getting rid of, for example, a lack of agreement between a pronoun and its antecedent, like the lack of agreement I have in the first sentence with “person” and “they,” even though George Eliot did that sort of thing all the time; or it means they’ve revised some perfectly good rambling but interesting sentences, like this one, into some neat and choppy, maybe even syntactically snarky, short sentences; or it means he/she has given it his/her English teacherly scrutiny, planting IEDs next to every adverb and witch-hunting for split infinitives, even though the formidably stodgy OED has declared that it is perfectly all right to occasionally split infinitives.

I worry when a person announces proudly that they’ve done a serious revision of something they wrote. Usually, that means they’ve proofread it with style sheet in hand, getting rid of, for example, a lack of agreement between a pronoun and its antecedent, like the lack of agreement I have in the first sentence with “person” and “they,” even though George Eliot did that sort of thing all the time; or it means they’ve revised some perfectly good rambling but interesting sentences, like this one, into some neat and choppy, maybe even syntactically snarky, short sentences; or it means he/she has given it his/her English teacherly scrutiny, planting IEDs next to every adverb and witch-hunting for split infinitives, even though the formidably stodgy OED has declared that it is perfectly all right to occasionally split infinitives.

In truth, most acts of revision are nothing more than attempts to make sure what you have written fits current rules and fashions. Conformity isn’t revision. Real revision is soul-work. It messes with your clear rational intentions and takes you to a much more interesting, and honest, place.

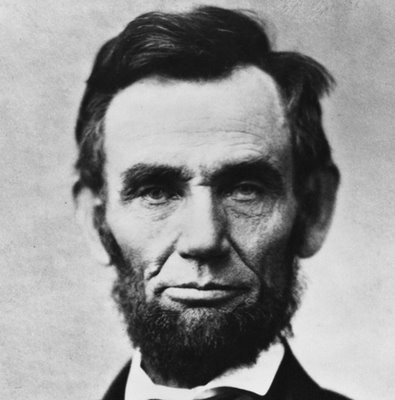

Take a look at two versions of the last paragraph of Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address. The first was written by Secretary of State William Seward; the second is Lincoln’s revision.

Seward’s draft:

I close. We are not, we must not be, aliens or enemies, but fellow-countrymen and brethren. Although passion has strained our bonds of affection too hardly, they must not, I am sure they will not, be broken. The mystic chords which, proceeding from so many battle-fields and so many patriot graves, pass through all the hearts and all the hearths in this broad continent of ours, will yet again harmonize in their ancient music when breathed upon by the guardian angels of the nation. (84 words)

Lincoln’s revision:

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature. (75 words)

The two versions appear in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals and again in the January 2009 issue of The New Yorker (with less punctuation – someone’s notion of revision?). I tried to imagine that I wrote both, the first as a promising rough draft and the second . . . well, the second after I dug deeper, after I did some soul-work. Lincoln was a great stylist, and some of the revisions are the result of a genius stylist, but I see a man going down into the depths of himself – or, I should say, a man allowing the depths of himself to rise like an artesian well to the surface.

Goodwin feels the most significant change is in the ending, where Seward’s “guardian angels,” who are removed from the human situation and looking down to send their blessing, are more personalized in Lincoln’s version, which places the solution within the “better angels” inherent to people themselves.

True enough, but the most profound revision is in the third word: “loath.”

I know I am embracing a basic paradox: We normally think of revision as an analytical skill, but the biggest step in becoming your own best critic is letting go of the analytical critic in the initial revision and being fully open and vulnerable to the emotional content of what you are writing. Lincoln didn’t just “close.” He was loath to close. Loath has the primary meaning of dislike, but there is that other meaning – i.e. reluctant. Lincoln no doubt also had in mind the lurking darkness of the German leid with its connotation of sorrow. Including the word “loath” was a profound insertion, one that has its roots not in stylistic polish or contemporary fashion but in his deep-feeling life. Lincoln’s revision follows his heart: It was painful to close because so much was hanging in the balance nationally.

Of course, at some point we do need to hone and prune to cut out stupid errors. But here’s the real message: Even in the honing and pruning stage, when you spot language that doesn’t measure up to the sentiment you intended, don’t desert the sentiment too quickly in pursuit of fashion or conformity; stay with the sentiment until you find the words that are both true to the sentiment and satisfying for you. William Stafford once told aspiring poets, “That poem is best that is most congruent with who you are.” I agree. Real revision is a process of allowing the language and sentiments to find their natural alignment.

Ah, brevity. I close.

—

Jim Heynen has a novel and a collection of short-shorts forthcoming from Milkweed Editions. His earlier work includes two young adult novels and several collections of short-shorts and poetry.

1 comment

Matthew Young says:

Nov 4, 2020

This is from Lincoln’s first inaugural address, not his second.