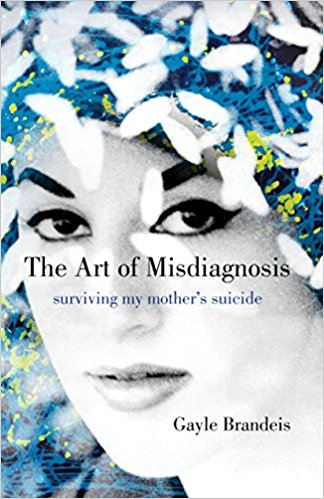

Diagnosis—and its constant cousin, misdiagnosis—form the intertwining narrative strands of The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide, which explores the storytelling and guesswork that often surround mental and physical illness. It’s a memoir about Gayle Brandeis coming to terms with her mother’s suicide, as well as a detective narrative that follows her as she pieces together the puzzle of her mother’s life and death. But, ultimately, it’s also about how perhaps everything can’t be figured out. Perhaps the best we can do is learn to live at the intersection of uncertainty and love.

Diagnosis—and its constant cousin, misdiagnosis—form the intertwining narrative strands of The Art of Misdiagnosis: Surviving My Mother’s Suicide, which explores the storytelling and guesswork that often surround mental and physical illness. It’s a memoir about Gayle Brandeis coming to terms with her mother’s suicide, as well as a detective narrative that follows her as she pieces together the puzzle of her mother’s life and death. But, ultimately, it’s also about how perhaps everything can’t be figured out. Perhaps the best we can do is learn to live at the intersection of uncertainty and love.

I have a personal stake in this memoir, since my father committed suicide several years ago. I understand viscerally how suicide survivors can be left with a heady mix of guilt and confusion, and I sympathize with the drive to find answers to the multitude of questions posed by this deeply traumatic event.

I, too, have been trying to write about my father’s suicide, so I’m grateful for the emotional and literary guidance that Brandeis provides with her narrative. She maps out the territory, with its many pitfalls, its blind alleys and dead-end streets. Certainly, every suicide is different, but there are some shared features to the experience of many suicide survivors, and this memoir—perhaps ironically in its very specificity—explores those commonalities. She takes the reader’s hand in this narrative and assures us that yes, with courage and creativity, stories of suicide can, and maybe must, be told.

Brandeis starts the book with a bluntness about her mother’s death that we later learn took her a long time to achieve: “After my mom hangs herself, I become Nancy Drew.” She explains that in the days following the death, she was looking for clues, evidence, answers. As she says, “I put on a detective hat so I won’t have to wear my daughter hat, so I can bear combing through her house.”

That emphasis on her attempts to solve a puzzle—to diagnosis what happened, based on the fragmented evidence left behind—is a theme that’s carried through the book. And, it turns out, that kind of effort to make sense of the world, the people one cares for, and one’s own mind and body, is something that Brandeis shares with her mother.

The book’s shadow narrative, the story behind the story, involves a film her mother was making near the end of her life called The Art of Misdiagnosis, about her own and her daughters’ experiences with a miscellany of physical and mental maladies that are, by turns, diagnosed, misdiagnosed, ignored, or fabricated entirely. Her mother’s obsession with the illnesses of her daughters obscures her own developing and mostly undiagnosed ecosystem of mental illness, which involves, among other symptoms, severe paranoia.

This book is a moving tribute to the ways Brandeis has inherited her mother’s relentless curiosity about the world and the people in it. As readers, we hear her mother’s voice—sometimes literally, in the form of quotes from the film’s script—woven with the voice of Brandeis. And it’s impossible not to recognize the similarities between mother and daughter, and the ways that Brandeis, in searching for the reasons for her mother’s suicide, replicates many of her mother’s patterns of truth-seeking and exploration. The primary difference is that the daughter’s narrative is firmly grounded in actual evidence, analysis, and clear-headed honesty. And for that reason, Brandeis is a trusted guide through the mysteries of her mother’s life, as well as her own.

Ultimately, the book ends in a place of compassion, resolution, and acceptance. Brandeis visits the place where her mother killed herself—a garage at an apartment building called Golden Oaks. On the way, she buys a rosebush called “Sun Flare,” and she takes it to the apartment complex. A woman at the front desk tells Brandeis everything she knows about the day her mother died, and she assures her that she’ll see to it that the rose is planted in the courtyard.

It’s a touching moment, one that the memoir earns by detailing the years-long, complex journey that Brandeis takes to get there. The sweet open-endedness of this visit offers a reconciliation that’s more vital and life-giving than any certainty ever could. As she says, “I had thought visiting Golden Oaks would bring me to my knees. I thought I would be wrecked by it; I thought I would be weeping so hard, I wouldn’t be able to see the road as I drove away. I never imagined I would leave feeling so light, so clear, rain delicious on my skin.”

___

Vivian Wagner is an associate professor of English at Muskingum University in New Concord, Ohio. She’s the author of a memoir, Fiddle: One Woman, Four Strings, and 8,000 Miles of Music (Citadel-Kensington), and a poetry collection, The Village (Kelsay Books). Visit her website at www.vivianwagner.net.