One mid-winter day, as I am walking around a frozen lake with my husband, a lifelong insomniac, we spot a muskrat. The small mammal is glassy-eyed and shuddering in deep snow with his pathetic hairless tail looped over bare toes.

One mid-winter day, as I am walking around a frozen lake with my husband, a lifelong insomniac, we spot a muskrat. The small mammal is glassy-eyed and shuddering in deep snow with his pathetic hairless tail looped over bare toes.

He should be sleeping in a cozy burrow, but like some misguided groundhog he’s awake, looking for spring. As we stand there pitying the muskrat, I am aware that my husband’s empathy is greater than mine, stretching out beyond what I feel, like some force field of warmth and compassion beaming its way across the snow bank to the blinking creature. My husband’s years of isolated nights, I realize, have brought this confused rodent as close as kin.

I’ve seen this cross-species empathy before. And I wonder if insomniacs, nature’s enemy, always side with the underdogs who find themselves in hopeless situations, battling the relentless cycles and seasons of life, those that won’t conform to their bodies’ habits and needs, to which their bodies, in turn, refuse to succumb.

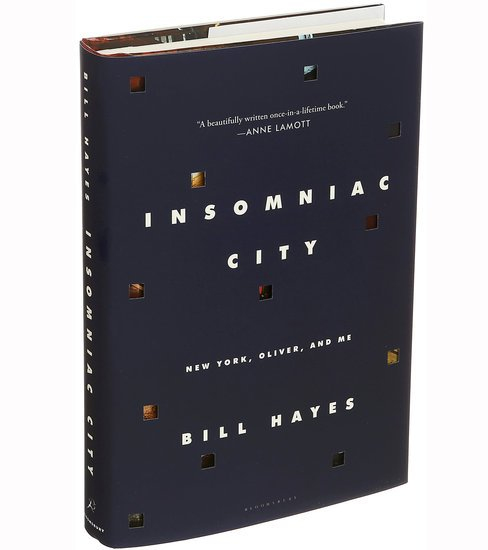

When he moves to New York City at the start of his book Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me, Bill Hayes immediately recognizes his insomniac self in the “haggard buildings and bloodshot skies, in trains that never stopped running like my racing mind at night.” His unique empathy extends not only to the city as an abstract concept, but reaches the individuals who inhabit its streets, especially at night.

Hayes’ forays into the city are almost always rewarded with a smile, a nod, a conversation, or even an invitation. Just as the empathy of the insomniac springs from a sense of isolation, perhaps empathy for the outsider on the streets of New York is born out of the fact that many drawn to that city feel themselves to be one. Hayes describes leaving his restless bed and strolling through a park, surprised to find other insomniacs inhabiting benches as if they were armchairs, reading books beneath street lamps. Here Hayes finds an affinity with his fellow nocturnal wanderers, the balm of companionship taking the edge off insomnia’s acute isolation.

Hayes moved to the city after losing his partner, Steve, who passed away suddenly after going into cardiac arrest one night in their San Francisco apartment. At the time of the incident, Hayes had sank into a rare deep sleep—a chilling irony that haunts him through the wakeful nights that follow Steve’s death. But this isolation is also what draws, or drives, Hayes into deep intimacy with New York City and its residents, relationships he establishes through his camera lens. “Can I take your picture?” is a constant refrain in Hayes’ book, and the resulting photographs stare up from the page, each an open invitation for connection.

Eventually Hayes forges a relationship with a fellow insomniac, the neurologist Oliver Sacks. The book becomes a tender remembrance of a great genius who learned to fall in love for the first time at the age of seventy-five. Hayes records his memorable interactions with Sacks in the form of journal excerpts interwoven with conversations with the strangers he meets in the city’s subways and streets.

Through Hayes’ lens, Sacks is a charming, musing intellect, whose fascination with the mysteries of the brain and the natural world are trumped only by the wonder he feels as he learns to share his joy with Hayes. “Billy! Shouldn’t one be on the roof? The sun is setting!” Sacks cries over the phone at one point, precluding any greeting. “Yes, one should!” Hayes replies, and Sacks rejoins: “I will meet you there!”

Sacks’ everyday reflections, as recorded by Hayes, serve to ground the younger author’s constant search for connection in the larger questions of life’s meaning, especially as Sacks begins to face death after his liver cancer diagnosis. “I don’t so much fear death as I do wasting life,” he bravely remarks to Hayes.

Sacks’ question, “How much can one enter, I wonder, another’s insides—see through their eyes, feel through their feelings? And, does one really want to…?” is answered in Hayes’ relentless empathy for strangers, and through the story of his deepening relationship with Sacks. Hayes affectionately depicts Sacks gradually learning to share his life, from lap swims to salmon, music to marijuana (the neurologist enjoys describing his vivid hallucinations whenever the two share a joint).

“Wouldn’t it be nice if we could dream together?” Sacks asks Hayes as their intimacy builds, and the reader can easily imagine the two insomniacs living happily together in the village Gabriel Garcia Marquez describes in chapter three of One Hundred Years of Solitude—a village plagued with communal insomnia.

Of course, the joy of infectious insomnia is that, unlike real insomnia, the inflicted are not alone. In the magical realism of Garcia Marquez’s novel, the village inhabitants walk around dreaming in a state of “hallucinated lucidity.” Not only do they see images from their subconscious come to life in their wakeful state, some, we are told, can see the images dreamed by others

While Insomniac City is inevitably book-ended by the ultimate isolation—death, the reader does not feel Hayes is alone at the end of his book. It is too easy to imagine that, after many wakeful nights without Sacks, who passed away in August 2015, the author will eventually drift off to sleep. And that, just as he begins to dream, he will hear a familiar voice crying, “I will meet you there!”

Neither does the reader feel alone while reading this book. My copy of Insomniac City was procured from my local branch of the public library. On page 65, overlaying one of Hayes’ black and white photos captioned “Just out of jail,” in which a lanky African American man looks back with relief and wonder in his eyes, a previous reader left a flower, its yellow petals pressed delicately between pages. This small offering from a stranger felt entirely fitting in this book, itself a gift to the lonely wakeful world.

___

Jodie Noel Vinson received her MFA in nonfiction creative writing from Emerson College, where she developed a book about her literary travels. Her essays and reviews have been published in Ploughshares, Creative Nonfiction, Gettysburg Review, Massachusetts Review, Pleiades, Nowhere Magazine, Rumpus, Rain Taxi, and Los Angeles Review of Books, among other places. Jodie lives with her husband in Seattle, where she is writing a book about insomnia.