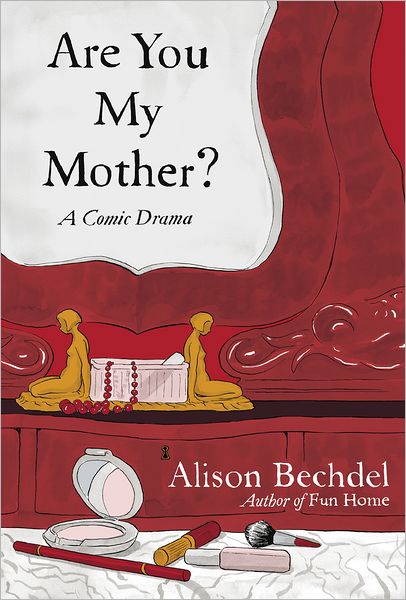

How do we understand our mothers or any topic that is so close to us, we are not sure where our selves end and the subject begins? As Alison Bechdel reveals in one of the many metanarrative moments of her graphic memoir, Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012,) the task is simultaneously impossible and necessary. Speaking to a therapist about her inability to extract herself from her mother’s influence, the narrator says, “I can’t write this book until I get her out of my head. But the only way I can get her out of my head is by writing the book.”

How do we understand our mothers or any topic that is so close to us, we are not sure where our selves end and the subject begins? As Alison Bechdel reveals in one of the many metanarrative moments of her graphic memoir, Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012,) the task is simultaneously impossible and necessary. Speaking to a therapist about her inability to extract herself from her mother’s influence, the narrator says, “I can’t write this book until I get her out of my head. But the only way I can get her out of my head is by writing the book.”

This conflict at the intersection of self, mother, and artistic creation motivates the book, which has been called a sequel to Bechdel’s best-selling Fun Home. However, to read it as a continuation of her debut memoir does the book a disservice. While Fun Home moved forward through narrative, building to revelations about erotic truth and the queer desire experienced by both the narrator and her father, Are You My Mother? circles around meaning. It is less of a memoir than a book-length essay about both her mother and the art of memoir. While the book contains elements of story, the narrative is secondary to the essaying, as the narrator tirelessly attempts to understand herself, her mother, and the world by juxtaposing memories with psychoanalytic literature and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. She is trying to understand not only her relationship with her mother, but also something about the nature of subjects and objects, about the self and the other.

Early in the book, the narrator warns us that this story has no beginning. Looking back to try to locate the story’s origin, she sees only a series of mothers and daughters, endlessly nested like Russian dolls. We feel Bechdel grappling from within her mother’s consciousness, trying to feel the outer contours, the shape of this doll that encloses her.

The book makes its way through these confined and murky spaces by opening each chapter with a dream. These dreams are depicted against black pages, with scenes often unbounded by panel frames. As the chapter follows the narrator into waking life, the panels are set against plain white paper, then return to a black background for the chapter’s final image, a two-page splash on a black background. This visual format creates an episodic rhythm, as the narrator emerges again and again out of the irrational, womb-like state of dreams and sleep into the world of daylight. Arriving at the final splash panel, the narrator returns to her darker internal reflections but with a new perspective, lingering on a moment as it spans a full inner spread in a graphic equivalent of Virginia Woolf’s “moments of being.”

Of course, topics like dreams, therapy, and questions of the nature of the self can be treacherous territory for a writer. “Language gets very confusing as it approaches this place where outside and inside touch,” Bechdel writes. Not only language, but perspective can break down at these points of unclear self-other relations, and the book could have easily devolved into self-absorption and sloppy abstraction. However, through a combination of vulnerability and fierce wit, Bechdel keeps her writing sharp and honest. The book, like the narrator herself, is painfully self-aware, and just as it told us there was no beginning, it also warns that there is no end. Are You My Mother? doesn’t build to any grand dramatic moment. Rather, it reveals how the art of writing and the art of living is found in an ongoing search for meaning. Resolution is delivered quietly, in obliquely satisfying moments as the mother and daughter can see each other more clearly. The narrator, no longer a nested doll, has forged enough distance for a tentative recognition of the wounds she shares with her mother. And the mother can see and accept the daughter’s art. “Well, it coheres,” the mother eventually acknowledges of the book.

—

Nuria Sheehan received the Iowa Outstanding Artist award for her short film, Wunderkind, which also screened at the Seattle Gay and Lesbian Film festival. Her essays have appeared in Anderbo, Blue Earth Review, and Sweet: A Literary Confection. She is currently completing her MFA in creative nonfiction at Hamline University.

1 comment

MJ LaVigne says:

Jun 12, 2013

A kind, but clear review.