When I was in the fourth grade, somewhere between learning about moving decimal points and the history of the California Gold Rush, I became aware of my body’s automatic responses—breathing, blinking, swallowing. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t hold my breath for long without the teacher noticing my red face, or turning from the board when she heard my defeated gasp as I gulped in greedily. Nor could I hold my eyes open without pinpricks of pain when they got too dry. Worse than being unable to accomplish these tasks, to prove myself in control of my body rather than the other way around, however, was the way that realization lingered. Long after I’d stopped trying not to swallow, I’d feel myself do it uncontrollably, wonder why and how, start swallowing repeatedly, unable to stop thinking about the movement.

When I was in the fourth grade, somewhere between learning about moving decimal points and the history of the California Gold Rush, I became aware of my body’s automatic responses—breathing, blinking, swallowing. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t hold my breath for long without the teacher noticing my red face, or turning from the board when she heard my defeated gasp as I gulped in greedily. Nor could I hold my eyes open without pinpricks of pain when they got too dry. Worse than being unable to accomplish these tasks, to prove myself in control of my body rather than the other way around, however, was the way that realization lingered. Long after I’d stopped trying not to swallow, I’d feel myself do it uncontrollably, wonder why and how, start swallowing repeatedly, unable to stop thinking about the movement.

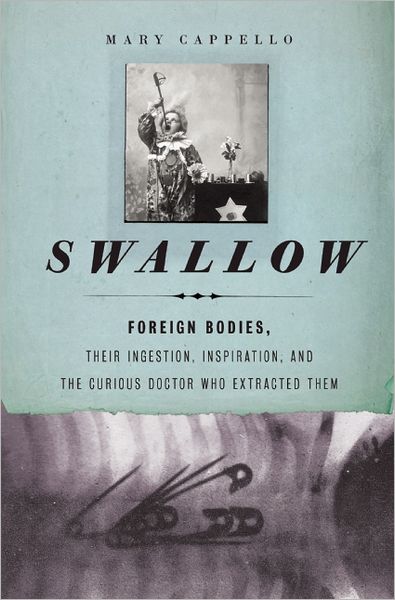

Mary Cappello’s Swallow: Foreign Bodies, Their Ingestion, Inspiration, and the Curious Doctor Who Extracted Them (The New Press, 2012) shares this curiosity. Cappello is intrigued by the body’s swallowing mechanisms, our reasons for swallowing foreign objects, and the man who paved the way for laryngology. In the early twentieth century, Chevalier Jackson invented over 5,000 instruments to remove a host of objects—pins and needles, screws and safety pins, small toys and coins, pebbles, padlocks, even belt buckles, coat hangers, and teacup handles—from patients’ airways without the need for traditional and often deadly surgery, objects he then collected and displayed.

It is Cappello’s fascination with his collection of foreign bodies that inspires the book, as she reflects on the history of medicine and the ways curious objects compel us, but her interest in Jackson’s life makes its way into her inquiry, the book moving between cultural history and biography as she seeks to understand the doctor and collector, a man said by many to have lived a life of solitude, friendless and driven by his work. Through her thorough research into voices in the field, inclusion of Jackson’s personal journals, and her careful speculation about his early life and the psychology behind his career, Cappello proves herself a friend to Jackson after his death, the care with which she investigates him evident in the prose.

Also woven throughout the book is a meditation on narrative, Cappello recovering the narratives behind several foreign bodies, giving voice to medical specimens long rendered silent by the conventions of science and time. As Cappello uncovers the lives behind the foreign bodies, restoring identities to their owners and enriching stark medical records with stories, Jackson’s collection becomes more than a gathering of odd objects, expanding to a narrative of ingestion, hunger, and satiety.

Resisting genre definition, Swallow moves seamlessly from medical records to the history of the field of foreign body extraction, Jackson’s journals to photos of his collection, interviews with Jackson’s patients to Cappello’s own reflections as a writer and patient. With a scholarly voice that is also poetic and humorous, Cappello describes the larynx in one moment and Jackson’s love life in the next, leading readers from a history of sword swallowers and circus acts to a philosophical meditation on how and why we swallow, always wondering with a surprising tenderness how the mouth and stomach function, what the difference is between swallowing and eating. The book’s lyricism is haunting—long after readers put it down, they will no doubt notice themselves swallowing, putting a finger or the end of a pencil in their mouth and, like a fourth grade student, wondering what it all means.

—

Sarah Fawn Montgomery holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from California State University-Fresno, and is currently a PhD student in creative writing at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her poetry and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in various magazines including DIAGRAM, Fugue, The Los Angeles Review, North Dakota Quarterly, The Pinch, and Puerto del Sol.