Her father doesn’t want the ringing telephone to interrupt his wife’s dying, so the phone is turned off. When his daughters remind him that there are people waiting to hear, wanting to know, he roars, “She’s dying. They all know. When she’s dead, you can call them and tell them she died, she’s dead.”

Saved message: “It’s Mom, hon. I’m laughing, I’ll tell you why in a minute. It’s 9:40 here. Are you there? Your father is out and I’m here. The Easter goodies are coming along real fine. Are you there? At twelve o’clock, get the broom and sweep the devil out of the house. Are you hearing this? At midnight, okay? After our Lord is risen. Don’t fall asleep. Sweep, sweep.”

The impossibility that she is dead.

He and his dying wife live up in the hills. Sometimes in winter they can’t get in or out for days. He cuts his own wood, shoots the squirrels in the bird feeders. He owns a red satin cape and is a Grand Knight in St. Anthony’s Knights of Columbus. “I look pretty good,” he says to the mirror adjusting the white sash, the feathered hat under his arm.

How impossible it is that she is dead.

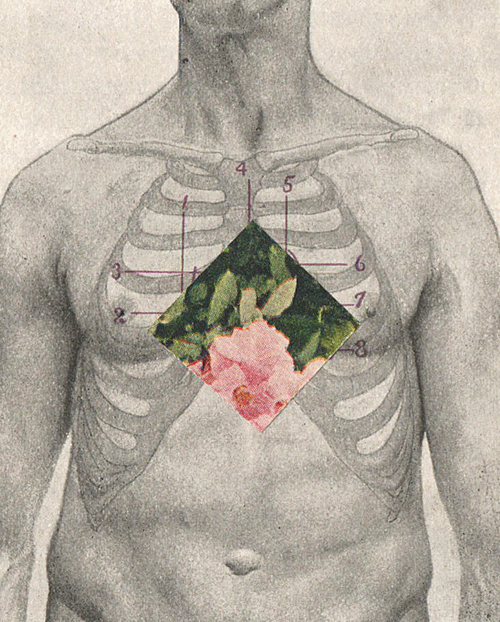

Death is invisible in the room that smells fur-lined, like a mouse cave. So many candles are burning, the daughters pant and glow. Jesus and Mary look down from the wall without mercy. “Ave Maria” plays on repeat. In the living room, a woman on the old stereo sings Ti voglio bene assai. There is a full-length mirror turned toward the hospital bed. Is death in the mirror?

Saved message: “It’s Mom, hon. I had the radio on in the kitchen and a song came on. There were no words, but it went her heart is breaking. When I heard it I remembered taking you and your brother to the pool that summer. You were eleven. You wouldn’t take off that robe to get in the water. You said you were afraid Mr. Sparky would spark you if you weren’t covered up. I never asked you, who was Mr. Sparky?”

It is impossible that she is dead.

“Do we cover the mirrors?” somebody asks.

“Now or after?” her sister says.

“I was sleeping, and I woke up and the phone was ringing,” her brother the drug addict says. He is as beautiful as a porn star until he smiles. “I heard Mom’s voice through the lines.” He is high voltage and alternating currents—off on, on off. “Her prescription is the same as mine. I can take the leftovers so they won’t go to waste. Where was she calling me from?”

The middle sister won’t enter the bedroom. After her lover left her, the mother cut the girlfriend’s face from all the family photographs. If the lover’s face was not near the edge of a photo, the mother covered her face with a Christmas sticker. The middle sister moves cars in the driveway for the people coming and going. She sits in her car, smoking up, and plays a song with guitars coming and going. Her hands are on the wheel, the guitars are driving.

The impossibility of her dead.

Her father was unfaithful many times. All his affairs are invisible shapes in the air waves. Does love come and go? Is love an action? A feeling? Is love inside or outside the body?

Saved message: “It’s Mom again, hon. There was one more thing. Every morning I pray for all my children, my loved ones. Another woman might get her real estate license, make stained glass windows. I dust the light fixtures, peel the potatoes, iron your father’s shirts. I leave you these messages. Call me please.”

Hang up the phone, he says.

Her father turns the music up louder. Just say I love him. The phone is still ringing and ringing.

__

Lynette D’Amico earned her MFA in fiction at the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. She has published work previously in Brevity and The Gettysburg Review. She is the content editor for howlround.com.

5 comments

“Faithful” by Lynette D’Amico | Friends of Writers says:

Sep 22, 2014

[…] “Faithful” by alumna Lynette D’Amico (fiction, ’13) appears at Brevity: […]

So the Was Turns to Is | BREVITY's Nonfiction Blog says:

Sep 25, 2014

[…] D’Amico on the origin of her essay Faithful, found in the newest issue of […]

Jackie says:

Sep 25, 2014

A beautiful essay!

Jayne Martin says:

Oct 13, 2014

An exquisite patchwork of emotion. Bravo!

Jerry Hemmerle says:

May 20, 2017

A fragmented Roman Catholic family experience of life and death well told!