Newborns can only see as far as the distance between their mother’s nipples and her face. For weeks, touch is how they understand this bright new world. They feel the warm and the cold. They feel the suck of air scouring their flesh. Until the 1980s it was believed that babies didn’t feel pain. When they required surgery, instead of anesthesia they were given muscle relaxers. They’d lie still and quiet, unable to move or cry as scalpels slipped their bodies open to the light of medical wisdom, a revelation of human anatomy in miniature.

Newborns can only see as far as the distance between their mother’s nipples and her face. For weeks, touch is how they understand this bright new world. They feel the warm and the cold. They feel the suck of air scouring their flesh. Until the 1980s it was believed that babies didn’t feel pain. When they required surgery, instead of anesthesia they were given muscle relaxers. They’d lie still and quiet, unable to move or cry as scalpels slipped their bodies open to the light of medical wisdom, a revelation of human anatomy in miniature.

* * *

In the Musti village of Solapur in western India, babies are dropped from the top of the temple’s fifty-foot tower and then caught on an outstretched bed sheet held taut by a throng of dutiful and worshipful men below. The babies feel the quick, curious tug of gravity shift their newly churning organs. They feel the abrupt impact and rebound, the hard hands of men lifting and passing them back through the crowd toward their grateful mothers. It’s a blessing, say the villagers, of good health and good luck.

* * *

The night my own baby cried through all my ritual efforts at rocking and bouncing and shushing and singing, she wouldn’t take a bottle and wouldn’t fall asleep. I shouted and shook her a little too forcefully and dropped her hard onto the new pink sheets of her crib.

I want to say it was only a few inches. I want to say I wasn’t myself, but babies, especially your own, have a way of showing you exactly who you are, or at least what you’re capable of in the middle of the night.

* * *

Every spring the villagers march together toward the temple tower singing and frantically playing their frame drums. It’s a celebration, a festive moment for everyone. They’ve been dropping babies here for five hundred years, and it’s said that not one of them has ever been hurt. They hold their babies out solemnly and let go. They offer them up, as we all must do, to the airy laws of chance.

* * *

The truth is I hadn’t slept much. The truth is I just wanted to get some sleep.

* * *

When Michael Jackson dangled his new baby over a crowd of fans gathered below his hotel balcony in Berlin, he was laughing like a child himself, like it was a joke, just some silly dare. No one could see the baby’s face hidden under the blanket, but his tiny, panicked legs kicked like a frog’s before Michael hurried back inside. It was all so sudden and awkward. People chanted, “Hey Michael, meet the family!” until he emerged once more, hid his own face behind a sheer white curtain, and tossed the baby blanket down into the baffled crowd.

* * *

I hum another song into the warm, furled blossom of her left ear. I let the cool white noise of the vacuum cleaner crash over us like insistent waves. I rock in the chair until it seems we might lift into the inevitable flight of dreams.

* * *

Imagine the falling faces of these villagers’ babies as their eyes go wild, and they open their writhing mouths to the faraway meaninglessness of the sky to make the only noise they know how.

I want to say the villagers are culturally backward. I want to say they’re barbarous and superstitious. I want to say this ritual is another example of the stupid things a belief in god or gods compels otherwise reasonable people to do. But I know the truth is something else.

* * *

I swear it shut her up for a second, the shock of landing in the crib, but the surprise hovering in her eyes, like a sudden illumination of this dark new world, stripped all the hush of its silence.

J.D. Schraffenberger is the associate editor of the North American Review and an assistant professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of a book of poems, Saint Joe’s Passion (Etruscan 2008), and his recent work appears or is forthcoming in DIAGRAM, Natural Bridge, Poetry East, Prairie Schooner, RHINO, and elsewhere. His essay “Full Gospel” appeared in Brevity 21 and Best Creative Nonfiction, Volume 1.

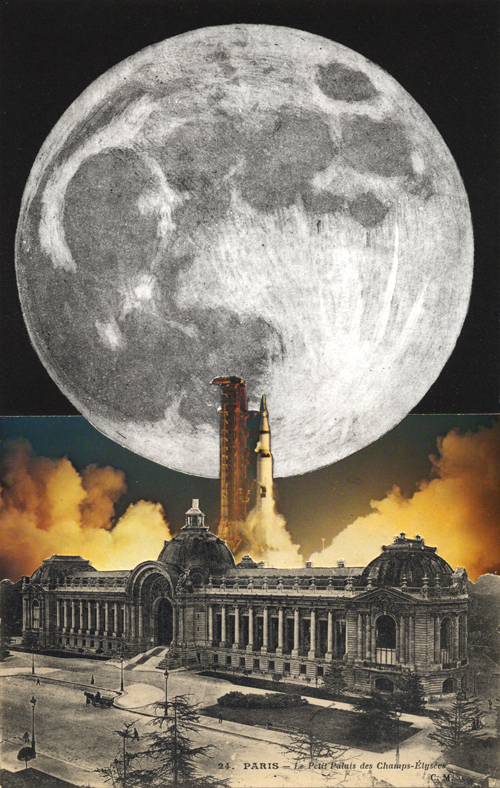

Illustration by Marc Snyder

12 comments

Karen Graney says:

May 22, 2012

How well this moves from the general to the personal and continues weaving, and I admire the poetry in this, including not hesitating to speak the truth, even of one’s own human frailty and its effect on one’s innocent child in the last three perfect phrases.

Thomas Gibbs MD says:

Jun 3, 2012

The first rule of obstetrics is don’t drop the baby. I have followed the rules and not dropped one. Still, there is an underbuttocks drape with a bag just in case. Everyone should feel better knowing that.

Post partum depression is under diagnosed. Writers of poetry and prose are not exempt. J.D. Schraffenbergers’s experience is not unusual. Her ability to write about it is.

Annam says:

Jul 3, 2012

I love the honesty of this piece, in both content and prose.

Jessica Baldanzi says:

Jul 9, 2012

So, so true and powerful. Parents feel so alone in those sleep-deprived moments when patience runs out. Thanks for sharing this so beautifully.

Paul says:

Sep 6, 2012

Very compelling. It was a nice ebb and flow between horrifying and fascinating.

lucinda kempe says:

Sep 6, 2012

I want to say it was only a few inches. I want to say I wasn’t myself, but babies, especially your own, have a way of showing you exactly who you are, or at least what you’re capable of in the middle of the night.

Yes, they do. Wonderful, truthful writing.

Joey Franklin says:

Sep 13, 2012

Interesting that Gibbs assumed the author was a woman. I did too reading it, even though I have put my own boys to bed almost every night for nine years, and the scene he was painting could have been me on some of my more exhausted nights.

Beautiful piece. Will share it with my students.

In Defense of the Nonfiction Confessional | BREVITY's Nonfiction Blog says:

Jun 24, 2014

[…] Though the hours together were long, my attention span was short. The combination of exhaustion and adrenaline made it difficult to concentrate on anything longer than a page or two. In addition to the circuit of parenting sites I visited daily (the rabbit hole of BabyCenter must be circled cautiously), I began reading my daughter back issues of Brevity, with its maximum 750-word essays. This is how, somewhere in my second or third week of parenting, I worked my way back to Issue 39, and J.D. Shraffenberger’s “Dropping Babies“. […]

J.D. Schraffenberger | B O D Y says:

Jul 3, 2014

[…] Essay at Brevity Poem at Paper Darts Short short at Revolver Author’s […]

On Dropping Babies and Mistaken Assumptions | BREVITY's Nonfiction Blog says:

Nov 12, 2014

[…] D’Aoust explains why she loves introducing students to J.D. Schraffenberger’s “Dropping Babies” from Brevity 39. Yes, we’re biased. Still, it’s a great discussion of […]

Tradition and the Individual Magazine by J.D. Schrafferberger | North American Review says:

Nov 21, 2014

[…] Waxen Poor (Twelve Winters), and his other work appears in B O D Y, Best Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, Notre Dame Review, Paper Darts, Poetry East, Prairie Schooner, and […]

Tradition and the Individual Magazine by J.D. Schraffenberger | North American Review says:

Nov 21, 2014

[…] Waxen Poor (Twelve Winters), and his other work appears in B O D Y, Best Creative Nonfiction, Brevity, Notre Dame Review, Paper Darts, Poetry East, Prairie Schooner, and […]