Fried chicken and sweet potato pie. Blatz beer on our father’s breath. That autumn Michael and I bagged leaves and burned weed with Anthony, walking house to house with a rake, ringing the doorbell and not running. He taught us how to ask for what we would be owed. We raked and mowed the small lawns of auto parts plant workers and huffed rags from the gas, irrevocably wrecked. Skinny cracker girl Franny, with the racist grandma, bent over Algebra equations on her front steps, put them down to dance for us with dark-skinned big-boned Carolyn. They did the Freak to an 8-track wax disco jam rising out of Mr. Robinson’s Lincoln Town car—doors opened, speakers blaring, he washed that damn car every day. My father sold things, drove long miles, then came home to fall asleep in front of the rabbit ears, my mother off to night school. I sat up late by an AM radio, singing the Isleys, O’Jays, Donny Hathaway’s “I’ve sung a lot of songs, I’ve made some bad rhymes.” Once Victor’s mother the nurse bandaged his hand while smacking him in the head repeatedly for being so stupid, burned by an M80 he didn’t toss fast enough. We were always daring things to explode in our hands. Davey’s father’s thick arms mapped with scars from the glass factory. Each of his six children wore those scars. And we were all the shards of shiny things, black pieces of coal pressed to diamonds in the pale Ohio light. We were newly shined fenders, carburetors and the grease of a socket wrench. We worshipped ex-ABA rebel ballers, Dr. J rising from the far foul line. We were the color of food stamps and free lunch, blue denim and wide lapels. We were funky as Patti Labelle chanting, Voulez-vous coucher avec moi ce soir? We were missed translations passed hand to hand on tiny slips of paper. We knew the secret signs, read them under a black light. Michael’s father, Vietnam Vet who sold weed, sat on the back porch, playing his beat up six-stringed guitar. Oh how he crooned those country tunes dreaming he was Charlie Pride. We’d tease his son till he swung an awkward jab then we’d fall down laughing on the cracked sidewalk, scraping our knees. We were Band-Aids ripped off fast. We knew the scars you can’t see are the ones that last. Mathew’s older brother smuggled us beers out the back door at the UAW hall. We drank them under the bleachers of Scott High and talked of hoops and high school dances we snuck into and whose bra we lied about undoing, or admired the tough older girls like Franny who teased what boy she let or slapped us down for getting too close and the places she would go, one day far away as Paris or Marrakesh, or the tenth moon of Jupiter. She smoked her filterless cigarettes and stared off at the horizon as the tornado sirens blared. She blew smoke in our faces, tugged on the strap to her halter top. She was doing the math. She already knew the metric system for starlight. The calculus for getting out—

Fried chicken and sweet potato pie. Blatz beer on our father’s breath. That autumn Michael and I bagged leaves and burned weed with Anthony, walking house to house with a rake, ringing the doorbell and not running. He taught us how to ask for what we would be owed. We raked and mowed the small lawns of auto parts plant workers and huffed rags from the gas, irrevocably wrecked. Skinny cracker girl Franny, with the racist grandma, bent over Algebra equations on her front steps, put them down to dance for us with dark-skinned big-boned Carolyn. They did the Freak to an 8-track wax disco jam rising out of Mr. Robinson’s Lincoln Town car—doors opened, speakers blaring, he washed that damn car every day. My father sold things, drove long miles, then came home to fall asleep in front of the rabbit ears, my mother off to night school. I sat up late by an AM radio, singing the Isleys, O’Jays, Donny Hathaway’s “I’ve sung a lot of songs, I’ve made some bad rhymes.” Once Victor’s mother the nurse bandaged his hand while smacking him in the head repeatedly for being so stupid, burned by an M80 he didn’t toss fast enough. We were always daring things to explode in our hands. Davey’s father’s thick arms mapped with scars from the glass factory. Each of his six children wore those scars. And we were all the shards of shiny things, black pieces of coal pressed to diamonds in the pale Ohio light. We were newly shined fenders, carburetors and the grease of a socket wrench. We worshipped ex-ABA rebel ballers, Dr. J rising from the far foul line. We were the color of food stamps and free lunch, blue denim and wide lapels. We were funky as Patti Labelle chanting, Voulez-vous coucher avec moi ce soir? We were missed translations passed hand to hand on tiny slips of paper. We knew the secret signs, read them under a black light. Michael’s father, Vietnam Vet who sold weed, sat on the back porch, playing his beat up six-stringed guitar. Oh how he crooned those country tunes dreaming he was Charlie Pride. We’d tease his son till he swung an awkward jab then we’d fall down laughing on the cracked sidewalk, scraping our knees. We were Band-Aids ripped off fast. We knew the scars you can’t see are the ones that last. Mathew’s older brother smuggled us beers out the back door at the UAW hall. We drank them under the bleachers of Scott High and talked of hoops and high school dances we snuck into and whose bra we lied about undoing, or admired the tough older girls like Franny who teased what boy she let or slapped us down for getting too close and the places she would go, one day far away as Paris or Marrakesh, or the tenth moon of Jupiter. She smoked her filterless cigarettes and stared off at the horizon as the tornado sirens blared. She blew smoke in our faces, tugged on the strap to her halter top. She was doing the math. She already knew the metric system for starlight. The calculus for getting out—

__

Sean Thomas Dougherty is the author or editor of fifteen books including the forthcoming The Second O of Sorrow and All You Ask for Is Longing: Poems 1994- 2014. His awards include an appearance in Best American Poetry 2014, and a US Fulbright Lectureship to the Balkans. He works in a pool hall in Erie, PA.

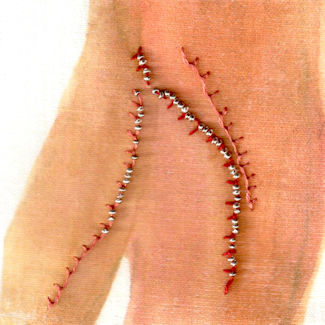

Artwork by Allison Dalton

23 comments

Marissa Neilson says:

Jan 23, 2017

Lovely

J.P.R. Campbell says:

Feb 6, 2017

There’s something intrinsic about the style of writing here which I love, it’s something that rings a bell but which I cannot place, it makes me nostalgic for a place I’ve never been in a time I’ve never lived.

My only misgiving is the lack of space. Without any paragraphs I’m faced with a wall of text which steals from the overall flow. Aside from that it is wonderful.

Sparkyjen says:

Feb 6, 2017

This story had me at fried chicken and sweet potato pie. Goodness, the wording feels so authentic. My visual sense had the best time. Thanks for sharing!

arcuff John says:

Feb 8, 2017

Lol yes you are right i feel the same

Azuree Soleil says:

Feb 6, 2017

Love this! You described my experience, although years earlier, so perfectly I can hear, see, feel and smell it. My experience was so much the same but so very different. Sometimes we say that the names have been changed to protect the innocent. In this scenario that is expanded beyond the names to the time, place, and gender; but it still rings true. I only hold out hope that those that followed us were, and are, able to experience some swatch of what we had because it was something special.

YossaAdrian says:

Feb 7, 2017

Good

pineas says:

Feb 7, 2017

I like it

Taxer biva says:

Feb 7, 2017

Wow that’s lovely

Taxer biva says:

Feb 7, 2017

Wow that’s lovely.i would love to hear more

Selma says:

Feb 7, 2017

Yes. That was a good read. Even though foreign to me it makes me feel like you’re telling my story. Yes, that’s it. I want to feel that again.

c c says:

Feb 8, 2017

Hey, thanks 4 sharing this…reminds me of my early years growing up in Lansing, MI.

Kimberlyn says:

Feb 9, 2017

Excellent imagery that evokes my own childhood near Toledo.

Autumn says:

Feb 9, 2017

This was so well-written. I felt like I was in the neighborhood.

LeAnna Crowley says:

Feb 9, 2017

Sounds so familiar. Thank you!

Cathy says:

Feb 9, 2017

Brilliant. This explodes with burnt energy.

Angie says:

Feb 10, 2017

Beautiful!

arusha topazzini says:

Feb 10, 2017

beautiful.

really good writing!

Brett says:

Feb 16, 2017

Sadly beautiful

Martha Bilski says:

Feb 17, 2017

Love this. Every image is a jewel.

DigitalPaper+ says:

Feb 20, 2017

Awesome read!!

Vicki Hendrickson says:

Mar 20, 2017

Good. Very good.

Nitesh says:

May 15, 2019

Thanks for This Information !!

Love this! You described my experience, although years earlier, so perfectly I can hear, see, feel and smell it.

Also, I Write About Toledo Ohio You Can Check Here

https://www.tripoyer.com/things-to-do-in-toledo-ohio/

JPEG Wall says:

Sep 27, 2020

Wow! Amazing article. Very inspiring!