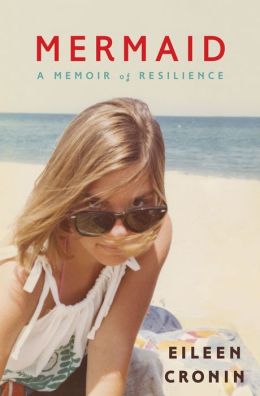

When I first picked up Mermaid: A Memoir of Resilience (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014) and flipped through the prologue, I began thinking about my own adolescence. I was the last of my friends to land a boyfriend. My German mother was known to serve weird salad. In third grade I pissed my pants in front of everyone. A girl in my grade claimed to have set up a series of chairs to assess my clinginess, and after she walked through them, she said I’d followed her like a cocklebur. Being an outsider is one thing when you’re a butter sandwich preteen with purple glasses growing up in Montana, but Eileen Cronin was missing legs.

When I first picked up Mermaid: A Memoir of Resilience (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014) and flipped through the prologue, I began thinking about my own adolescence. I was the last of my friends to land a boyfriend. My German mother was known to serve weird salad. In third grade I pissed my pants in front of everyone. A girl in my grade claimed to have set up a series of chairs to assess my clinginess, and after she walked through them, she said I’d followed her like a cocklebur. Being an outsider is one thing when you’re a butter sandwich preteen with purple glasses growing up in Montana, but Eileen Cronin was missing legs.

I respect Cronin for laying out the terrors, failures, and triumphs of her most vulnerable years. Sometimes she asks us for sympathy, while other times she pushes us away. However, she never strays far from humor as she navigates embarrassing questions, bullying, and her budding sexuality.

The first pages are set in Florida during spring break. Here Cronin is a young college girl who just wants to feel beautiful and normal. She writes, “Back in Cincinnati I am ‘that girl who was born without legs.’ Yet here on spring break in Fort Lauderdale I become a beautiful girl with a limp.”

She dances with a guy who compliments her on her well-toned arms, but what she doesn’t explain is that “biceps like these come from lifting the dead weight of my entire being every time I get out of a chair.” She doesn’t tell him that she once stepped out of her car to find the foot she’d been driving with was still on the floorboard. On the dance floor, the guy spins her around and won’t stop. You can guess how this ends. Cronin tries to be normal and fails, but she picks herself up and tries again. Her failures hurt, but the way she keeps trying for success is mesmerizing. At a young age she realizes, “People would tell me that no one saw me differently, but I knew that only some people saw me as the same. My job would be to find those people.”

Cronin is nearly four when she realizes her legs are different—both end at the knee, one above and one below. Later she’s fitted with prosthetics, which she calls “flesh-chewing baseball bats.” Squiddled is the word Cronin’s sister uses for the way she moves, a cross between crawling and walking on her knees. Growing up in Cincinnati, in the 1960s, Cronin is born to Joy, a Catholic chain-smoker who takes pride in being an unlikely parent—“part Blanche DuBois, part circus trainer, and mostly a pregnant Lucille Ball.” Joy seems mental unbalanced for much of her life, which might have played a role in Cronin’s birth defect.

The central question is, did Joy take thalidomide (a drug later found to cause birth defects) when she was pregnant? Even as a child, Cronin wanted to know what happened when she came into the world without legs and was told she just “slipped out like a piece of raw meat.” Cronin is relentless in demanding her mother tell her whether or not she took this drug.

Cronin does some research and learns limb buds typically appear around the end of the first month. Limbs are formed by the end of the third. She figures her legs likely stopped developing between four and ten weeks. She also studies the stereotypes surrounding thalidomide-deformed children. The Greek word terato means monster, and “thalidomide prompted the creation of the term ‘teratogen,’” defined as an agent causing embryo malformation. She wonders if her mom took the drug in Germany.

It is understandable then that, as an adult, Cronin has a tense relationship with her mother. “The main reason I couldn’t bring the idea up was that she’d made it clear to me that she had ‘no guilt whatsoever’ about my birth defects. She had nothing to discuss,” says Cronin. Her siblings call her Snarleen when she pushes for details, yet still she keeps asking. One day she calls her mom and asks again about Germany. This time, she discovers her mother “had been providing clues to the truth all along. For instance, she’d always made a point of saying that she was pregnant with me on her trip to Germany…maybe she’d wanted me to figure it out.” Sometimes it pays to be Snarleen.

Cronin’s struggles make me wish I had not only been less hard on myself as a child, but also more bold and free-spirited. I wish I’d clocked a bully with my lunchbox like she did. I was so insecure about my body that I refused to go skinny-dipping, while she bared herself on an entirely different level by placing a leg aside in a stranger’s pool. Mermaid shows how us how resilience makes us stronger, particularly when we’re fighting forces beyond our control.

—

Maria Anderson is from Montana and lives in Providence, RI. Her writing appears or is forthcoming in the Atlas Review, Metazen, the Fiddleback, NY Arts Magazine, and others. You can find her online at http://mariaanderson.net/.