Lyons Press 2009

Two women huddle near a computer screen preparing for a Skype call with a young blog consultant. One woman is a seventy–five-year-old visual artist. Computer is not her native language. The other a writer and a competent computer user, thought she could help as she knew a few things about digital conversations —at least she thought she did until she tried to create a blog for the artist. Stress of an impending fellowship deadline that required sample art in a digital format didn’t help. Rules to blogging—part technical, part cultural convention— caused them to turn to the young consultant. A gamer growing up, he knew a few things. After all, much of the digital world was created by people with deep histories in gaming.

Two women huddle near a computer screen preparing for a Skype call with a young blog consultant. One woman is a seventy–five-year-old visual artist. Computer is not her native language. The other a writer and a competent computer user, thought she could help as she knew a few things about digital conversations —at least she thought she did until she tried to create a blog for the artist. Stress of an impending fellowship deadline that required sample art in a digital format didn’t help. Rules to blogging—part technical, part cultural convention— caused them to turn to the young consultant. A gamer growing up, he knew a few things. After all, much of the digital world was created by people with deep histories in gaming.

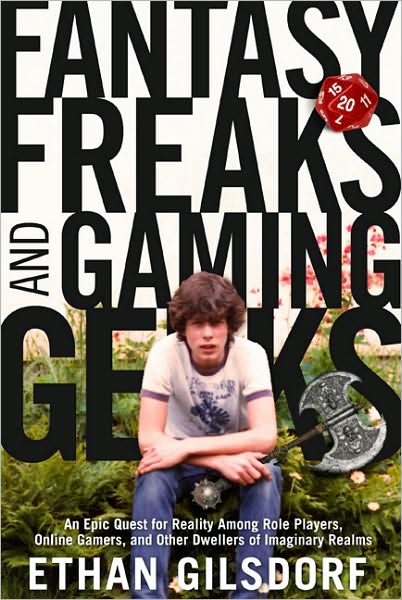

In Fantasy, Freaks, and Gaming Geeks, Gilsdorf maps this gaming history from 1970s board games to the worldwide Internet activity today. His own experience began in 1979 when he was in eighth grade. To escape the trauma of a mother who fell ill after an aneurysm, he and a group of friends reveled in the myriad of rules of Dungeons and Dragons. Twenty years later, Gilsdorf began exploring gaming in Atlanta, Georgia, dressing as a monk scribe in black yoga pants and a borrowed blue tunic in the world of Larpers—live action players. He met a “pointed-ear green veined goblin” and wondered how gaming integrated with real lives.

Subsequently Gilsdorf found a former lawyer working in Guedelan, France, on tile floors for the replica of an ancient castle—a tangible project for a person who once performed abstract legal work. Gilsdorf learned that the 2008 Obama campaign ran ads inside the Xbox 360 digital racing game, no longer merely the activity of geeks and outcasts as Gilsdorf once was in eighth grade. The author was present when 14,000 people populated Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at midnight waiting for their copies of the newly released Harry Potter and the Death Hallows. Here real and imagined lives intermingled.

For Gilsdorf, what began as an investigation into misfits addressing monster fears turned into a study on humans desire to grow. Gilsdorf considers emotional growth as he watches gamers stretch their capacity to absorb multiple expressions of themselves through avators—“on-screen representations of a player.” Gilsdorf’s observations remind me of myth scholar Joseph Campbell who said we are living in a time without valid myths to guide our actions through important life transitions. Is fantasy filling the gap created by this absence of myths? Gilsdorf wonders. “Perhaps to get one’s driver’s license, one should have to fight an orc … Perhaps before we die, we should all write in bound leather books with quill pens in calligraphy the stories of our lives to pass on what we knew to those who’d live after us.”

Returning from New Zealand’s Middle Earth, Gilsdorf makes one final trip to view the original Tolkien manuscripts kept at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Gilsdorf writes that the calligraphy was “gorgeous.” My artist friend and I take great comfort in knowing that Tolkien wrote with a fountain pen. If such a man can be a legend today among gaming geeks, perhaps we too can learn to dialogue in the digital age.

—

J.Luise Eberhardy is currently working on a book, Creating Meaningful Work: What People Do and How It Impacts the World, focused on global activists, artists, and entrepreneurs creating new work for the next generation. Eberhardy is the founding partner of Wiv Inc, a company that strengthens the creative thinking processes in work teams. She teaches writing at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.