This is 1986, and I am seven in Seattle, and Miss Erika is French from Canada with a black leotard and a tight bun twisted like a seashell. Miss Erika is French, and Edgars Kleppers is the only boy in ballet class, but I am still required to play Fritz, the only boy in the Nutcracker ballet. This is 1986, and Edgars Kleppers has too many Ss in his name, and there are 13 girl-ballerinas and only one boy—one ballerino. Though I am not the best in my class at math, I know that Edgars should be Fritz and that I should be a sugar plum fairy in a pink tutu with red rouge-smears on my cheeks. This is 1986 in Seattle after all, and Miss Erika brings us chocolate-covered ants to eat after final curtsies the way they do in her part of Canada, which is not France but close. I am seven and a girl, and Edgars Kleppers is a silly, stupid ballerino in shiny warm-up pants and purple sweatbands—but Edgars has a beautiful sister. Edgar’s beautiful sister is called Diana, like the goddess of the moon, who we aren’t allowed to worship in Christian school. I am seven, and I go to West Seattle Christian School, and I want to be a sugar plum fairy like all the other girls, understanding that Diana, who is a perfect ballerina and whose legs split all the way open in the air like someone unzipped her from the suit of her body, must play Clara, because she is more girl than most girls. This is Christmastime in 1986, and while Miss Erika likes Diana best, I know, she also likes Edgars, who is not afraid of making mistakes and who can arabesque higher than maybe I ever will despite his shiny pants and flat black slippers and the fact that he is a boy and should be doing something else besides dancing. But then my father says you can’t blame Edgars Kleppers for being a little strange because, after all, his mother died, and it’s hard for kids to find their way without a mother. My mother thinks I should play a sugar plum fairy like the rest of the girls, but when she comes to see Miss Erika, we are standing in a row at the barre, plié-ing and plié-ing, and their conversation goes on so long that my legs want to collapse beneath me, and Miss Erika says we all look like little wilted flowers, then laughs in her French-Canadian way. I count the moles on Miss Erika’s back, round and raised like licorice drops, and I tell her, “No, Edgars is theballerino!” and she says, “Yes, that’s right!”—this is the French word for a male principle dancer—so it seems I am good with language and bad with ballet, and she dresses me up in another kid’s karate suit and sends me running out on stage to steal the Nutcracker doll from Clara—to drop and break it in front of the Christmas tree and the Chief Sealth High School auditorium crammed with parents and rocking prams, which I know is the British word for stroller. Then, Diana, who is playing Clara but who is really a perfect ballerina beneath her green velvet dress and doilie collar, bends down and wraps a kerchief around the broken doll—which is not really broken, but only pretend—and twirls around holding the nutcracker as the audience applauds. Then, the sugar plum fairies appear, through an ornamental pattern of piqué turns, until they are stopped in their tracks by Edgars, puffed with pride in his Mouse King costume. This year, because of Edgars, the Mouse King isn’t played by somebody’s dad, and though I have offered, thinking a Mouse King is surely better than a mischievous boy, Miss Erika stands with her hand on my back as we watch from the wings, telling me my time will come. For what? I wonder. This is 1986 in Seattle after all, and I feel the capsize in my chest like a rowboat caught in a storm, and when they raise the curtain, I will be the girl in the back dressed like a boy in a borrowed karate suit, taller than everyone but not quite so nimble or quick. I will not be sure whether to bow, curtsy, or do nothing at all.

This is 1986, and I am seven in Seattle, and Miss Erika is French from Canada with a black leotard and a tight bun twisted like a seashell. Miss Erika is French, and Edgars Kleppers is the only boy in ballet class, but I am still required to play Fritz, the only boy in the Nutcracker ballet. This is 1986, and Edgars Kleppers has too many Ss in his name, and there are 13 girl-ballerinas and only one boy—one ballerino. Though I am not the best in my class at math, I know that Edgars should be Fritz and that I should be a sugar plum fairy in a pink tutu with red rouge-smears on my cheeks. This is 1986 in Seattle after all, and Miss Erika brings us chocolate-covered ants to eat after final curtsies the way they do in her part of Canada, which is not France but close. I am seven and a girl, and Edgars Kleppers is a silly, stupid ballerino in shiny warm-up pants and purple sweatbands—but Edgars has a beautiful sister. Edgar’s beautiful sister is called Diana, like the goddess of the moon, who we aren’t allowed to worship in Christian school. I am seven, and I go to West Seattle Christian School, and I want to be a sugar plum fairy like all the other girls, understanding that Diana, who is a perfect ballerina and whose legs split all the way open in the air like someone unzipped her from the suit of her body, must play Clara, because she is more girl than most girls. This is Christmastime in 1986, and while Miss Erika likes Diana best, I know, she also likes Edgars, who is not afraid of making mistakes and who can arabesque higher than maybe I ever will despite his shiny pants and flat black slippers and the fact that he is a boy and should be doing something else besides dancing. But then my father says you can’t blame Edgars Kleppers for being a little strange because, after all, his mother died, and it’s hard for kids to find their way without a mother. My mother thinks I should play a sugar plum fairy like the rest of the girls, but when she comes to see Miss Erika, we are standing in a row at the barre, plié-ing and plié-ing, and their conversation goes on so long that my legs want to collapse beneath me, and Miss Erika says we all look like little wilted flowers, then laughs in her French-Canadian way. I count the moles on Miss Erika’s back, round and raised like licorice drops, and I tell her, “No, Edgars is theballerino!” and she says, “Yes, that’s right!”—this is the French word for a male principle dancer—so it seems I am good with language and bad with ballet, and she dresses me up in another kid’s karate suit and sends me running out on stage to steal the Nutcracker doll from Clara—to drop and break it in front of the Christmas tree and the Chief Sealth High School auditorium crammed with parents and rocking prams, which I know is the British word for stroller. Then, Diana, who is playing Clara but who is really a perfect ballerina beneath her green velvet dress and doilie collar, bends down and wraps a kerchief around the broken doll—which is not really broken, but only pretend—and twirls around holding the nutcracker as the audience applauds. Then, the sugar plum fairies appear, through an ornamental pattern of piqué turns, until they are stopped in their tracks by Edgars, puffed with pride in his Mouse King costume. This year, because of Edgars, the Mouse King isn’t played by somebody’s dad, and though I have offered, thinking a Mouse King is surely better than a mischievous boy, Miss Erika stands with her hand on my back as we watch from the wings, telling me my time will come. For what? I wonder. This is 1986 in Seattle after all, and I feel the capsize in my chest like a rowboat caught in a storm, and when they raise the curtain, I will be the girl in the back dressed like a boy in a borrowed karate suit, taller than everyone but not quite so nimble or quick. I will not be sure whether to bow, curtsy, or do nothing at all.

—

Born in Seattle in 1979, Julie Marie Wade completed a Master of Arts in English at Western Washington University and a Master of Fine Arts in Poetry at the University of Pittsburgh. She is the author of 2 collections of lyric nonfiction,Wishbone: A Memoir in Fractures (Colgate University Press, 2010) and Small Fires (Sarabande Books, 2011), and 2 collections of poetry, Without (Finishing Line Press, New Women’s Voices Chapbook Series, 2010) and Postage Due (White Pine Press, Marie Alexander Poetry Series, 2013). Julie lives with Angie and their two cats in the Bluegrass State, where she is a doctoral student and graduate teaching fellow in the Humanities program at the University of Louisville.

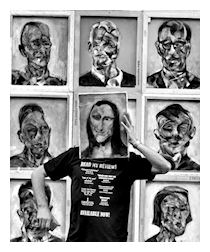

Photo by Dinty W. Moore