Free Press, 2010

No one much cared that Uncle Eugene veered from the truth when he told his stories, particularly after a few knee slaps, window-rattling howls, and tears brought on by laugher. At eleven years old, though, I didn’t fully grasp this. During a sleepover with my cousin, my uncle launched into a bedtime story, telling us about a city couple who years earlier had moved into a cabin high on the ridge. One winter’s night, the man pulled out a gun, shot his wife in the head, then turned the gun on himself. No one ever knew exactly why he did it, though old-timers blamed it on “cabin fever.”

No one much cared that Uncle Eugene veered from the truth when he told his stories, particularly after a few knee slaps, window-rattling howls, and tears brought on by laugher. At eleven years old, though, I didn’t fully grasp this. During a sleepover with my cousin, my uncle launched into a bedtime story, telling us about a city couple who years earlier had moved into a cabin high on the ridge. One winter’s night, the man pulled out a gun, shot his wife in the head, then turned the gun on himself. No one ever knew exactly why he did it, though old-timers blamed it on “cabin fever.”

Maybe it was just the way Eugene left the story hanging out there, undone, as if I could almost picture it, but not. I didn’t sleep, haunted by a series of unanswerable questions. By daybreak I had decided that if I wanted any peace, I would need to see this cabin for myself. So I talked my cousin into taking me there, in spite of her emphatic pleas: it was miles away, we’d get lost, we could run into a bear or mountain lion. Still I insisted.

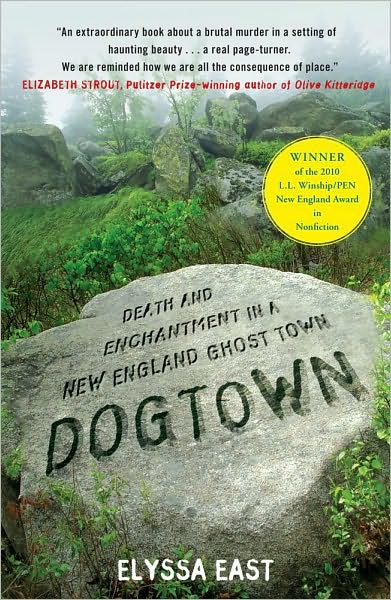

Thus, obsessing over a place, drawn by a mystery, is something I understood and it drew me to Elyssa East, an art history student spellbound by a place called Dogtown, which Marsden Hartley had painted. Hartley had described this primordial land, located on Cape Ann, Massachusetts, as a cross between Stonehenge and Easter Island. While he referred to the land’s curious monumental stones, he seemed to also suggest something unsettling.

In 1999, East bought a map of Dogtown, loaded up her pick-up truck, and set out to see exactly what Hartley had painted. Locals warned her not to go into the woods—not alone anyway. That’s because in 1984, a popular school teacher, Anne Natti, had hiked in there and was bludgeoned to death.

Not easily deterred, East visited the 3,000-acre woodland and began a decade of research, which she’d turn into a braided narrative centered on Natti’s murder but woven with four centuries of really weird and creepy tales. East reveals that Dogtown is a colonial ghost town, originally settled in 1645. It grew to one hundred settlers who mysteriously fled in the mid-1800s. No one knows why they left, though East has some theories.

Abandoned like this, Dogtown with its giant boulders, swamps, old roads, and rock homes attracted itinerants, gypsies, witches, and various odd characters. Roger Babson (founder of Babson College), hired stonecutters in the 1930s to inscribe “inspirational” dictums on the rocks: use your head; help mother; spiritual power; and never try never win.

Expecting this to be a book about Hartley (a curious individual himself), I felt a twinge of disappointment when East ditched him early in the story. That didn’t last long. East immediately grabbed me by the collar and led me through some of the most fascinating annals in New England history.

My cousin and I, for our part, searched for that cabin for years, hiked up hills and through creek beds, twisted our ankles, slashed our arms, and scarred our bodies with chigger bites. Still, we never caught even a glimpse of that place. Likely it never existed—a secret my Uncle Eugene took to his grave. However, East proves that some mysterious places really do exist and bear secrets worth telling.

—

Debbie Hagan teaches creative nonfiction and mystery writing at New Hampshire Institute of Art and is editor-in-chief of Art New England magazine. She is also Brevity’s book review editor.