University of Nebraska, 2010

Recalling the first time he heard the song “Tom Sawyer,” essayist Patrick Madden writes, “Rush became my sounding board, my tolling net, my filter for apprehending the world.”

Recalling the first time he heard the song “Tom Sawyer,” essayist Patrick Madden writes, “Rush became my sounding board, my tolling net, my filter for apprehending the world.”

Confession: While Madden says he loves Rush for “their awareness of self, the world,” this is exactly why I never cared for them. Rush takes me back to the college dorm room dominated by the inevitable “Starman” poster. For hours I would sit on a carpet remnant as this guy (who could be cute if he lost that middle part and untucked his shirt) laboriously explicated significant passages from his holy text, “Exit…Stage Left.” I would shift my cramped legs, reapply my lipgloss and think, Are we going to make out or what?

Twenty years later, Patrick Madden’s collection of essays, Quotidiana, makes me reconsider my past impatience. Maybe I should have given the Rush guys more of a chance. What’s wrong, really, with caring a little too much?

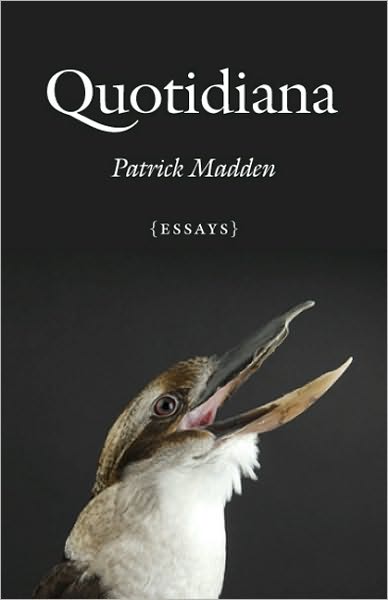

A large part of Madden’s appeal is his genuine caring about the world. He cares about his deceased grandmother and quarks. He cares about the laughing owl (Sceloglaux albifacies), chorister Sister Vecchio in the Danubio Branch of the Mormon Church of Montevideo, his dog, and the sufferings of historical figures. He cares about the “number of stars in the heavens” and “the motes of dust in the earth.” Madden’s curiosity and affection for the world engages and persuades. I can’t imagine better company for a mountain hike.

Quotidiana means “the everyday, the ordinary,” and Madden’s stated goal as an essayist is to be a “keen observer(s) of the overlooked, the ignored, the seemingly unimportant.” At times he pushes the boundaries of his premise. There is after all, an essay called “Momento Mori.” But then again, there is also an essay called “Garlic.” Madden plays fast and loose with form, jumping from lists to illustrations to personal stories to explications of mathematical proofs. Just when the reader might worry that Madden is Icarusing on gravity and the nature of being, he tosses in a Lovin’ Spoonful reference. Through anecdote he proves Galileo’s discovery that objects be they large and small, when dropped from a tower, hit the ground at the same time.

Madden respects his elders. Truthfully, there are times when Madden could loosen his grip on the European masters—(a few less Montaigne quotes). In the introduction, quotes take over (i.e., Are we going to make out or what?). What keeps the essays percolating is the buoyant tone. Like Neil Peart lyrics on Cervantes or Kubla Khan, Madden is inviting us to geek out with him. Isn’t this awesome? I can hear him saying. Check out Rabelais! Madden understands the power of the essay to blur narrative threads, meander, permutate, invent, and defy convention. But that’s no reason to get snooty about it.

At our local karaoke bar last week a poet brought down the house with his rendition of “The Spirit of Radio.” This was an unlikely success, a tiny miracle. When people want a sure fire hit they usually reach for “Strokin'” or “Bust a Move.” But the crowd’s response was undeniable. The entire bar united in joyous chants, boundaries dissolved in a pump-your-fist-say-yeah celebration.

And so there it is. Smart can be fun.

—

Kelly K. Ferguson has a creative writing MFA from the University of Montana, and is working on a PhD in nonfiction at Ohio University. Her fiction and essays have appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Mental Floss Magazine, Defenestration, and Poets & Writers.