For two months last summer, my husband and I lived in a cabin in Oregon, where I shared my friend Nell’s garden. Every day at first light, I would go out to see if the beans had sprouted, the squash blossoms opened, the tomatoes reddened overnight. After hours of weeding, I’d return to the cabin with dirt smeared across my forehead, tangles in my hair. My husband said I’d never seemed happier or more beautiful.

Growing up, I never raised so much as a radish. My family had lost the bequest of its long-ago immigrant forbearers, Old World gardening know-how. And in doing so, like many Americans, we had lost our connection to the land. When it came to gardening, and maybe only then, Bartolomeo Vanzetti was luckier than I.

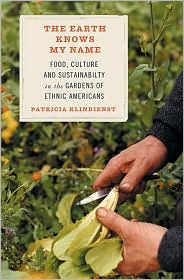

Vanzetti, an Italian immigrant to America, was murdered by the state for a crime he did not commit. Yet on the eve of his execution, he found peace remembering his father’s garden in Italy. In her compassionate and hopeful book, The Earth Remembers My Name: Food, Culture, and Sustainability in the Gardens of Ethnic Americans, Patricia Klindienst asks, “If a garden holds this power for the gardener in a moment of extremity, might it hold this power at all times, but we just don’t see it?”

Klindienst tells the stories of ethnic Americans whose lives are rooted in their native gardening traditions. Through tending farms and yards and city plots, they have created refuge and continuity, and preserved their cultural heritage. Some, like the indigenous Tewa of Tesuque Pueblo in New Mexico, or the Gullah community on St. Helena Island, have been in the U.S. for centuries. Others, like the Khmer Growers or the Puerto Rican gardeners of Nuestras Raíces in Massachusetts, have arrived more recently. All fifteen gardens in this book offer hope for the rest of us. Gardening feeds the hunger for family, community, home, and a sustainable future.

I don’t own a square inch of soil. But I’m becoming a farmer anyway. Last year in my living room, I grew sixty tomato plants from seeds I’d saved; when the plants grew big enough, I gave most away to friends who enjoyed bumper crops from their balconies and backyards. Last night, I ate red chard from the window box outside my kitchen, and butter lettuce from the pots on the fire escape. One seed at a time, one meal at a time, I am rooting myself to the earth, reclaiming my own ancient connection.

—

Tracy Seeley grew up in Kansas, lives in San Francisco, and longs for chickens. Her memoir,My Ruby Slippers, about her quest for a sense of place, is forthcoming from University of Nebraska Press.