Summer mornings, I often walk along the two-track unpaved driveway that leads from my family’s secluded cottage on Lake Superior to the paved road. I pass under mature birches and weedy Manitoba maples, my flip-flops treading an old dirt-and-stone path. In the 1920s, my grandfather carved it through the forest with a handsaw and built it up along a cliff, moving boulders using a block and tackle.

Summer mornings, I often walk along the two-track unpaved driveway that leads from my family’s secluded cottage on Lake Superior to the paved road. I pass under mature birches and weedy Manitoba maples, my flip-flops treading an old dirt-and-stone path. In the 1920s, my grandfather carved it through the forest with a handsaw and built it up along a cliff, moving boulders using a block and tackle.

For more than fifty years, I’ve crawled, toddled, and run along this path. I know the plateau where a windstorm in the ’90s blew down a stand of balsam that still needs to be cleaned up, and where over-exuberant alder has blocked views of the lake.

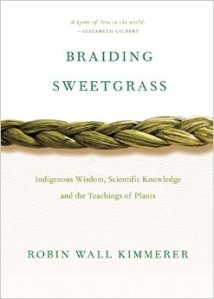

Ten years ago, I left the US to settle in Canada, because I’d always loved my summer visits and never wanted to leave. Learning to love winter in northwestern Ontario has been a challenge. But summer—well, I thought I knew this place in summer. Yet lately I look at that familiar path with new eyes, all because of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

I picked up this book in part to learn about the natural world, and in part to learn from models of successful individual essays.

I expected lessons, but what I found were teachings—knowledge that’s offered, instead of information and dogma.

Yes, Kimmerer is a botanist, who speaks about the natural world with a scientist’s authority. She’s also a Potawatomi woman, who’s dedicated to traditional ways of knowing and sharing her knowledge. This book braids these multiple perspectives into a series of essays that’s coherent and compelling.

In indigenous stories, sweetgrass (Hierochloe odorata in Latin; wiingaashk in Anishinabemowin) was one of the first plants to grow on the earth. The chapters in this book fall into sections based on the ways indigenous people interact with sweetgrass: planting, tending, picking, braiding, and burning. Individual chapters combine stories and ruminations that wander through myriad subjects (wild strawberries, mast fruiting, water lilies) and settings (a weed-choked pond, a superfund site, the Kentucky mountains, a forest research station).

Language-lovers may find “Learning the Grammar of Animacy” particularly interesting. In it, Kimmerer describes learning, as an adult, the Potawatomi language. In contrast to noun-intensive English, Potawatomi relies on verbs that grant living status to just “things” in English, such as the “days of the week” or “a bay.” She writes, “‘To be a bay’ holds the wonder that, for this moment, the living water has decided to shelter itself between these shores, conversing with cedar roots and a flock of baby mergansers. Because it could do otherwise—become a stream or an ocean or a waterfall, and there are verbs for that, too.”

Kimmerer communicates with insight: “To be heard, you must speak the language of the one you want to listen.” That is written in an essay that appears to be a scientific paper about the growth habits of sweetgrass. In fact, it ponders points of friction between academic science and under-represented perspectives. She speaks frankly of the difficulties facing women in science, and the disdain academic scientists have for indigenous knowledge.

In these essays, Kimmerer sends out a gentle, affirming call to act on behalf of our world, using our creative gifts: “books, paintings, poems, the clever machines, the compassionate acts, the transcendent ideas, the perfect tools.” Being grateful is important, Kimmerer says, but not enough. Everyone must act.

Since reading Braiding Sweetgrass, I’ve turned my walks into “compassionate acts.” Instead of eyeing spots to apply my chainsaw, I notice the woodpeckers have been at that dead spruce, deer have created a new path around the brush pile, and the eagle seems fond of the birch snag. Instead of imposing my will, I try to support these creatures, and write with more freedom and passion.

__

Marion Agnew writes fiction and creative nonfiction in an office overlooking Lake Superior. Her work has appeared in literary journals and Best Canadian Essays (2012 and 2014). She’s currently writing a novel that includes families, bears, and clearing brush.