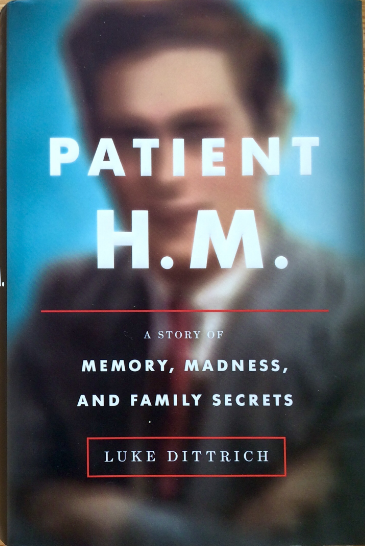

Luke Dittrich has a stark inheritance. His grandfather, William Scoville, was the second most accomplished lobotomist in the history of medicine. This prominent neurosurgeon at Hartford Hospital had a career that ran parallel with one of the most scientifically fruitful and morally dubious periods of our medical advancement: the early and mid-century era of American psychosurgery. While this brilliant anti-hero looms over the story, Dittrich’s preoccupation is primarily with the result of his grandfather’s most famous miscalculation in Patient H.M: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets.

Luke Dittrich has a stark inheritance. His grandfather, William Scoville, was the second most accomplished lobotomist in the history of medicine. This prominent neurosurgeon at Hartford Hospital had a career that ran parallel with one of the most scientifically fruitful and morally dubious periods of our medical advancement: the early and mid-century era of American psychosurgery. While this brilliant anti-hero looms over the story, Dittrich’s preoccupation is primarily with the result of his grandfather’s most famous miscalculation in Patient H.M: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets.

Henry Molaison had been afflicted with severe epilepsy much of his life when he consulted Dr. Scoville about further possibilities for treatment. With little more than a hunch, Scoville suggested a medial temporal lobectomy, and on August 25, 1953, he drilled two trephine holes into Henry’s skull, vacuuming out nearly all the contents of the medial temporal lobes—his amygdala, uncus, entorhinal cortex, and hippocampus. The result of the operation was a form of anterograde amnesia. No definitive improvement had been made to Molaison’s epilepsy, but now, at twenty-seven years old, he could not form new memories.

Molaison’s brain began processing his life in spans of mere minutes. He often repeated himself mid-conversation and had no recollection of what he was doing. Within a few short years, young Henry had become Patient H.M., a medical phenomenon who helped uncover new ground in the science of memory. Hundreds of academic papers were written about his case, and much of his remaining life (he died in 2008) was spent as a test subject for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.), answering sensitive questions or performing challenging tasks under observation without compensation. Molaison was a willing and often cheerful participant.

Dittrich deftly draws together diverse shards—surgical practices from ancient Greece, his grandmother’s treatment at an asylum, the Nuremberg Code, Walter Freeman’s lobotomobile— without ceding control of Molaison’s troubling story. While Dittrich achieves a subtle, grounded panoramic, I waited for a more visceral reckoning with his family’s past. Instead, he is a cool authorial presence, questioning and considering rather than staking his own convictions.

For this reason, episodes from Dittrich’s own life, such as a stint in Egypt as a young reporter, can read like distraction. They are a kind of reportage, an additional tessera in an already complex mosaic, rather than the gut-wrenching reflection I sought and believed this writer could give. Still, it is Dittrich’s personal connection that gives the story its true gravity.

It’s why I picked up the book— and why many friends have sent me articles about Patient H.M. I too have a personal stake in the story of psychosurgery. In 1967, my own grandfather was treated with an experimental surgery in his medial temporal lobes because he had experienced violent blackouts. After nearly ten months of treatment, this distinguished engineer and father of seven was divorced and living on the opposite coast. He had become permanently unemployable and in constant confusion and pain. He frequently had delusions that his doctors were still doing tests on him, still stimulating sections of his temporal lobes by a remote control to see how he reacted. An unsuccessful $2 million lawsuit was filed against his doctors. My grandfather spent the majority of his remaining life in a psychiatric ward of the VA Hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts.

Dittrich is wary of judging this troubling history with a contemporary lens—a concern I share. He calls the temptation of anachronistic outrage “presentism”—a temptation I grapple with. This journalistic posture prevents his outright condemnation. Instead he offers sharp questions to the medical establishment that allowed patients who needed treatment for their illnesses to become unwitting subjects of career-building experiments. His mostly evenhanded tact has still elicited vigorous response from the scientific community. Dittrich has come under fire from M.I.T. for claims he made about Suzanne Corkin, Molaison’s longtime researcher at M.I.T. Shortly after his book’s publication, Dittrich became the subject of a letter printed in New York Times which was signed by over 200 scientists and disputed his characterization of Corkin.

If there are shortcomings or missed opportunities in Patient H.M., its ambition and scope make it an impressive page-turner. A harrowing and controversial finale recasts this well researched narrative into a drama with Shakespearean hues. It left me reeling.

The history of psychosurgery and the life of Henry Molaison are vital because they reveal a callous disregard that can exist among even the most revered doctors in our society. We must be reminded of their fallibility. The consequences are too grave.

__

Mike D’Angelo is a teacher and writer who lives in Massachusetts. He holds a BA in classics from the University of New Hampshire and has studied at Union Theological Seminary and the University of New Hampshire’s MFA program. Mike is at work on a book about the life of his grandfather Leonard Kille.