The other day, I came across a stack of letters, written in 1974, by my high school boyfriend. When I left for college, he stayed home. We couldn’t afford to talk by phone, so we wrote.

The other day, I came across a stack of letters, written in 1974, by my high school boyfriend. When I left for college, he stayed home. We couldn’t afford to talk by phone, so we wrote.

Reading the first letter, I hear this sweet boy’s voice, almost as if he were next to me. How can this be? I haven’t spoken to him in nearly forty years. I smile at his unflagging optimism: Can we get engaged? I’ve picked out our rings. We’ll get a place and live happily ever after. In the margins were scrawled love poems and cartoons with shaggy characters holding up signs: I miss you; I’m lonely. He had pressed so much love into these pages, I could feel his arms reaching for me, his kisses so sweet. This magical feeling lingered for days.

From 1914-1946, artist Georgia O’Keeffe and photographer Alfred Stieglitz wrote 1,900 letters. Jennifer Sinor found them in Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library and read them all.

At age twenty-seven, O’Keeffe wrote to Stieglitz wanting to subscribe to his magazine Camera Work. Months later, she sent him a few of her charcoal drawings.

“What am I to say?” he wrote back.

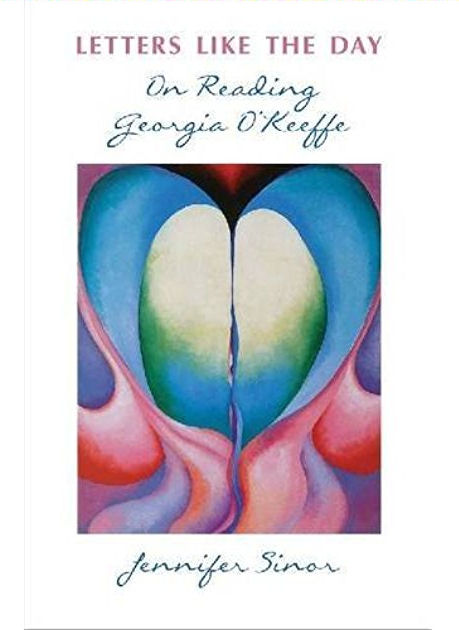

“This is from the man who would hold court for hours at 291, his gallery and what would be the cradle of American modernism,” writes Sinor in her essay collection, Letters Like the Day: On Reading Georgia O’Keeffe. “This is from the man who would roam and rage from one topic to the next—art, politics, religion, the nature of reality—yielding the floor to none.” This is from the man who was twenty years O’Keeffe’s senior and already married.

Stieglitz had never met anyone like O’Keeffe. No one had possessed her passion, independence, and mulish drive to forge past brutal rejection and ridicule. She’d earned his respect, and it melted his curmudgeonly heart. In 1918, O’Keeffe moved to New York City. In 1924, she married Stieglitz. Five years later, she moved to New Mexico’s desert canyons, going east now and then to visit her husband. While distance kills many romances, these dreamy, impassioned letters sustained it.

In her letters, O’Keeffe professes she can’t articulate her ideas. Not true. Sinor uses her letters to offer an intimate, fresh look at this enigmatic artist through nine innovative essays. In “Holes in the Sky,” she imagines the artist physically dropping by for tea. It’s a clever way for her to metaphorically show that voice brings the work alive, so much so the letter writer’s presence is felt.

Her letters also give us insight into the way O’Keeffe thinks, her obsession with the voids. As Sinor describes it, “Not the bone but what can be seen through it. And what she saw was both beautiful and sad, terrifying and sublime, a space so complex, and charged, and personal, that words would never capture it.” Like O’Keeffe, Sinor is drawn to space, the narrative gaps that stimulates reader reflection.

“More Feeling Than Brain” is a richly woven collage made up of evocative events that occur during Sinor’s trip with her family through the desert. Her son yearns to see a coyote: “We have been waiting and waiting and waiting.” Then early one morning, they hit one with their car—hardly the way a child should meet his favorite animal. Death, longing, shock, Christian symbolism, and the vast, striking beauty of the desert make up this complex tapestry over which the writer weaves O’Keeffe’s haunting words: “I work in a queer sort of unconscious way: more feeling than brain.”

While each essay possesses its own intrigue, I’m drawn to the subject matter in the slightly amusing narrative “Perfectly Fantastic.” Dole Pineapple Company invites O’Keeffe to Hawaii to create paintings of its farm, scheduled to appear in a national ad campaign. Do the pineapple kings not realize that O’Keeffe’s eye goes to the desert—stark, angular, and full of voids? In fact, Hawaii’s lush, dense vegetation flummoxes the artist. She can’t find her way into it. Then she stumbles upon a lava-flowing volcano. She paints with fury and can’t stop. This is hardly what Dole had in mind.

“Her Hawaii paintings may not be her best work, and her time in Hawaii may not, ultimately, have been one of her most significant periods in her life,” writes Sinor. “What we have though, in these paintings and in her letters is the story of how we come to know—a place, a flower, a self.” O’Keeffe dared to look where most us don’t. Through her vision, paintings, and letters, we’re able to fully see and appreciate this artist’s own intoxicating vision of truth.

__

Debbie Hagan would write more letters, but there are only a few people around who can still make sense of her cursive. She’s the former editor-in-chief of Art New England, and current book reviews editor for Brevity. Her essays have appeared in Hyperallergic, Pleiades, Superstition Review, Brain, Child, and elsewhere. She’s a visiting lecturer at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.