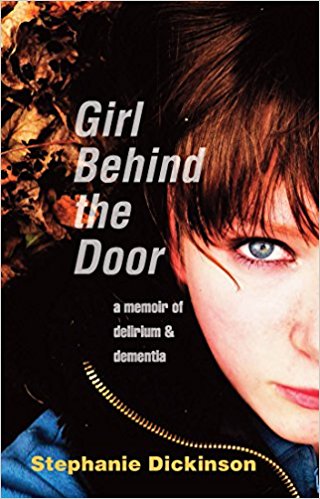

Ideally, a memoir’s title suggests the author’s tone as well as his or her overall vision for the work. Stephanie Dickinson’s Girl Behind the Door: A Memoir of Delirium and Dementia brings to mind Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. As with Stein, who isn’t Toklas, Dickinson isn’t Girl. But whereas Stein actively “pretends” to be Toklas, Dickinson’s mother Florence (Girl) serves as a prism through which Dickinson both overtly and covertly reveals her own life in addition to Florence’s.

Ideally, a memoir’s title suggests the author’s tone as well as his or her overall vision for the work. Stephanie Dickinson’s Girl Behind the Door: A Memoir of Delirium and Dementia brings to mind Gertrude Stein’s The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. As with Stein, who isn’t Toklas, Dickinson isn’t Girl. But whereas Stein actively “pretends” to be Toklas, Dickinson’s mother Florence (Girl) serves as a prism through which Dickinson both overtly and covertly reveals her own life in addition to Florence’s.

We meet Florence in her ninety-ninth year gripped by sudden mental illness, mushrooming beyond any non-medical person’s comprehension, and in hospice care. With Dickinson at her side, we learn that to Florence, Dickinson is a “failed daughter” for never marrying or producing children and for partnering with someone who eats more than he earns. Florence considers Dickinson a “financial disaster” who can’t provide a home for her in her old age. So, when Dickinson refers to herself as a “typist” rather than a writer and criticizes her dead-end job, one she’s held for years, we begin to intuit that Florence has so overwhelmed Dickinson’s sense of self that Dickinson, despite decades of adulthood, continues to absorb Florence’s disparaging pronouncements.

From Dickinson’s earliest memories, she felt dismissed, writing, “Growing up it felt as if my brothers were given more weight, and I was invisible.” Florence, too, felt dispensable. As a child, she was sent away from her family’s Iowa farm to help with an only slightly younger, pampered cousin. It’s then she became “the girl behind the door,” unseen and irrelevant.

Dickinson’s efforts to achieve an identity separate from Florence is fueled by coming of age in the 1970s. At this same time, I was a teenager with a single mother who was active in her church, economically strapped, older than her husband, raising three children alone, beholden to family, and wielding high expectations. Embarrassingly, Dickinson’s cocksure invincibility, drug use, solo hitchhiking, and straining to break free ring true to me. But my recklessness pales beside the author’s. Her personal accounts of rape, stealing from Florence, vehicular recklessness, and getting shot point blank (knocking out her teeth and causing injuries that inflict lifelong pain) are not only frightening, but make my misadventures appear safe. Dickinson’s rebellion knows no bounds. She refuses to adhere to behaviors and values cherished by Florence. Not one suggestion offered by Florence warrants following. “Not one.”

Dickinson renders the violence of dying a “natural death” in hospice care with the same poet’s eye she portrays her miscreant early years. Each word lights up the page as if it were a much-observed, beloved Iowa firefly: “stars shivering,” “an opera of breeze.” With a talent for language, Dickinson creates an unflinching portrait of Florence, granddaughter of Bohemian Czechs who immigrated to Iowa during the American Civil War. In Dickinson’s hands, generations come to life on their prominent Iowa farms. As the inheritor of their sultry auburn hair, blue eyes, and lean voluptuousness, Florence receives eight marriage proposals before marrying Chicagoan Phil Dickinson in 1946. They’d met in Nevada after Florence’s WWII Red Cross service in Arizona and California. Phil’s love of poetry and Bible quotes “elevated” him in Florence’s eyes. Newly married, they returned out West on Phil’s Harley-Davidson.

When Phil dies young from a heart condition, Florence’s stoicism shifts from dutiful wife to sole provider. She learns Braille for a teaching job and tends to her children’s souls with nightly family Bible readings. The pressure she applies to high schooler Dickinson to play the organ for church services typifies what eventually sets Dickinson off for New York City in her mid-thirties.

Despite the masterful prose, at times I found Dickinson’s narration unreliable. She and brother Brett played dolls together as children and wrestled as adolescents in their off-limits living room, but Dickinson claims to have grown up “lonely as a weed.” Reconciling such contradictions would have intensified the interiority and unified the work on a deeper level. Confessed personal failings embellish the action, but also supplant greater reflection.

The most significant shift belongs to Florence. After decades of belittling, she, “dementia mom,” uncharacteristically forgets her daughter’s renegade past long enough to offer the empathy Dickinson craves. Amidst this forgetting, Dickinson assumes her position in the dwindling rank of family members uniquely qualified to remember.

___

Rita Juster earned an MFA in fiction from Queens University of Charlotte and serves as senior fiction editor for Carve Magazine, an online and print literary journal that publishes fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. After meeting her husband and raising three children in Dallas, Texas, the empty nesters currently live in midtown Manhattan where Rita is completing a memoir.