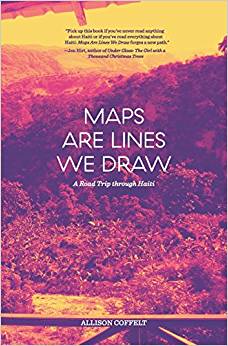

It’s a rare person who doesn’t like to travel. I know, because I am one, and when new acquaintances discover this about me, they often look as if I’ve pushed aside my bangs to reveal a third ear. But even though I don’t enjoy travel, I have immense curiosity about the world outside my living room. It’s a blessing when a book about a place I am never likely to go crosses my path, and a great joy when that book is also well-written and thoughtful. Such is the case with Maps Are Lines We Draw, a slim and piquant little volume about Haiti laid out along a road trip the author, Allison Coffelt, takes through the country with a doctor who is delivering her to OSAPO, the medical clinic he founded. There, she will provide assistance; not, I gather, because she has any special medical training, but because she is simply another pair of hands. Maps is an immediate book, told with great craft and without pretense. The author’s voice is so strong, full of such intellect and sensitivity, that it’s difficult not to like and respect Coffelt right away.

It’s a rare person who doesn’t like to travel. I know, because I am one, and when new acquaintances discover this about me, they often look as if I’ve pushed aside my bangs to reveal a third ear. But even though I don’t enjoy travel, I have immense curiosity about the world outside my living room. It’s a blessing when a book about a place I am never likely to go crosses my path, and a great joy when that book is also well-written and thoughtful. Such is the case with Maps Are Lines We Draw, a slim and piquant little volume about Haiti laid out along a road trip the author, Allison Coffelt, takes through the country with a doctor who is delivering her to OSAPO, the medical clinic he founded. There, she will provide assistance; not, I gather, because she has any special medical training, but because she is simply another pair of hands. Maps is an immediate book, told with great craft and without pretense. The author’s voice is so strong, full of such intellect and sensitivity, that it’s difficult not to like and respect Coffelt right away.

Let me dispense with the elephant in the manuscript: yes, this is a white American’s book about a visit to Haiti. Yes, there are elements of this premise that feel off, as if an anthropologist is observing a struggle of which she is not really a part. Obviously, she can leave that struggle at any time to return to her comfortable Midwestern life. But Coffelt underlines her awareness of her privilege, and the validity of her project, repeatedly and effectively. On page fifteen, barely having begun her story, she warns the reader:

Maybe a guide keeps you physically safe—but what of other wickedness?

The danger of the mission-trip story. The college-admittance or finding-God experience. You know the one: a student goes somewhere “down there,” and as soon as she gets off the plane (“it was really hot”) they take a bus to the village, and they meet locals and maybe teach some children English, and at the end of the week, that glorious week, when all this time she thought she would be teaching them, she really finds they taught her. A tale so common I once heard a radio interview about just how common it is.

I’m not sure knowing this trap gets me out of it.

I’m not sure I’m so different.

The book is not just the story of Coffelt in Haiti. She also spends many pages on aspects of the relationship between Haiti and richer countries that are not commonly known. For example, clothing recycling, which bundles up clothing donations from North America and ships them to countries like Haiti more or less for disposal, is quite harmful to these countries, and Coffelt outlines the reasons why. “Haiti is a graveyard for clothes,” she notes. Methods of long-distance aid that wealthy countries like the U.S. presume to be helpful often are not, for reasons it’s impossible to tease out without a perspective like Coffelt’s: ground-level interaction with citizens of a nation coupled with a high-altitude capacity to understand the entrenched systems at work. She methodically explains how, in the early nineteenth century, France manipulated Haiti into promising an astronomical sum to its enslavers to compensate for the end of free labor on the island. The unfairness of this situation gathered in my mind so gradually that I was furious and disgusted at the end of the chapter without consciously realizing I’d passed beyond curiosity.

Coffelt’s ability as a writer is not restricted to reportage. Some chapters are structured almost as braided or lyric narratives. She mixes a mouthwatering description of eating douce macoss, a unique dessert, with paragraphs describing the medical education of the doctor who is driving her across the island. There’s collage here, as well; for instance, impressions of Haiti sourced from a 2011 Lonely Planet guide, a 1956 Pan Am brochure, and the people Coffelt meets at the clinic, are mixed together and presented simply:

The adage, “there’s room for interpretation.”

–You wash your hands, your dishes, with Clorox.

The adage, “a good translator disappears.”

–I buy the rice from the farm. We boil it. After that, we dry it in the sun and go to a grinder to grind and clean it. Then we sell it in a public market.

–Why are you a nurse?

–I love the community, and I want to help people and also help my family.

Further, Coffelt returns repeatedly to an exploration of “t/here”: there and here, the American Midwest and Haiti, swapping places. Since there and here are relative to a person’s present location, socioeconomic situation, race, education, health, and other factors, “t/here” does not form a simple binary but a shifting, unreliable set of landscapes. She even writes about Hegel. It’s cool and sad and wonderful and dismaying all at once.

Since I’m not a traveler, I’m not qualified to say whether Coffelt has accurately captured Haiti. What she’s certainly done is produced a profoundly thoughtful volume about place, medicine, light, opportunity, water, and storytelling, among other ideas. Were I her editor, I might have wanted her to write more, to open up her bleak, tightly controlled sentences and build something that feels more comfortably complete—stories with resolutions instead of shrugs and sorrow. But perhaps that is Coffelt’s point: from here to there, and from there to here, prejudice, purpose, and even lives are all going to be lost. The spaces between certainties are where a book like this lives, and Coffelt has manipulated those liminal spaces with great skill.

___

Katharine Coldiron‘s work has appeared in Ms., the Rumpus, the Offing, and elsewhere. She lives in California and blogs at the Fictator.