In 1992, my husband and I, grabbed the opportunity to live in southern Germany for two years. To prepare, we hired a Berlitz instructor, who laughed at our feeble attempts to make the German “r” sound—a scratchy, back-of-the-throat growl. She shook her head and said, “It doesn’t matter. All Germans speak English.”

In 1992, my husband and I, grabbed the opportunity to live in southern Germany for two years. To prepare, we hired a Berlitz instructor, who laughed at our feeble attempts to make the German “r” sound—a scratchy, back-of-the-throat growl. She shook her head and said, “It doesn’t matter. All Germans speak English.”

Unfortunately, we discovered upon our arrival, this was not true. In our cute Bavarian town of Ingolstadt, we could not understand a word the locals said. They spoke bayerisch, a medieval dialect spoken with dark guttural vowels, a loopy drawl, and words that one needed a bayerisch dictionary to understand. A few shopkeepers acted as if they understood our butchered-up hochdeutsch. They spoke back, but between the accent and the local dialect, we were lost.

We had so much to do: find an apartment and buy a kitchen (cabinets, sink, stove, refrigerator, faucet) and lights. In Bavaria, the kitchen and lights are part of one’s own personal furniture. The lights ran on 220 volts, so we also had to be careful not to electrocute ourselves when wiring them up. We were strangers in a strange land—and not always welcomed. It’s a feeling that has stuck with me, especially when I meet foreign visitors or immigrants struggles with language. I worry if they feel lost too?

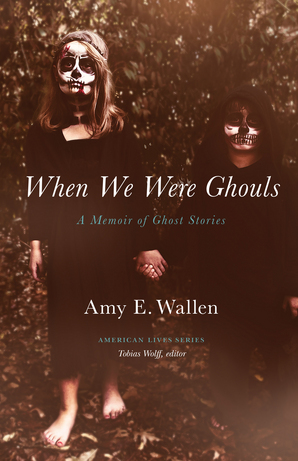

I thought of this while reading When We Were Ghouls, by Amy E. Wallen. She’s a lot like I was—an outsider, facing strange customs with a bit of fright and awe. Though she’s just a child, she moves from one chaotic, unstable country to another.

It begins with one of the compelling openings I’ve read in a long time. Wallen, just eight years old, is perched atop a pre-Inca graveyard in Peru, digging with her parents for pots, fabrics, and wrapped corpses. She unearths a skull that’s not only intact but has a silver band wrapped around it. Her father tells her, he was a prince, and the silver band is what’s left of his crown. He tells her, they’ll keep it. Maybe they’ll turn it into a lamp.

“We were ghouls. We had no respect,” admits Wallen’s mother when the author, while writing this book, asks, were they really grave robbers?

They did remove ancient objects from a burial mound, the mother admits. However, she didn’t think the objects had any real value. Bones and pottery were everywhere.

“Her denial is vexing,” Wallen writes. “Denial, the finest form of forgetfulness.”

Yet, this book isn’t so much about her crazy family’s mistakes. It’s more about being a child survivor, adapting to situations uncomfortable and bizarre. “Something about me likes having a family made up of looters, grave robbers, and ghouls. The Munsters incarnate,” she writes.

Her parents are mercurial, Bohemian-types, reminiscent of Jeanette Walls’ in The Glass Castle (albeit, Wallen’s seem a bit more enterprising and mentally stable).

The family ends up in far-flung, semi-dangerous places, such as Nigeria, Peru, and Bolivia.

Wallen’s father, employed by Phillips Petroleum, explores oil drilling sites. Their first move sends them to Nigeria, where seven-year-old Wallen suddenly realizes, “We had a new way of life, and it didn’t include the Piggly Wiggly anymore.”

The father is gone most of the time. The sister and brother attend school in Switzerland. Even Wallen’s mother leaves, returns to the United States to attend her mother’s funeral. So Wallen is home alone, under the supervision of the housekeeper and driver.

An active, inquisitive child, Wallen dodges her caretakers and wanders out of the family’s compound, On the streets of Lagos, curious Nigerian children flock around her. “They took turns touching my arms, rubbing their hands down my forearm, back and forth, then giggling and trading places with another kid in the back of the crowd,” she writes.

The driver panics when he realizes the girl is missing and runs to the street calling, “Little Sister.” Eventually he finds her, coaxes her home. There, Wallen asks, What were the children doing?

He replies, “They just want see if it rubs off.” It was the white of her skin.

At Christmas, the family reunites, but no one is able to find a real Christmas tree. Pine trees don’t grow in Nigeria. Thus, they borrow a silvery tinsel tree from a Norwegian family. It comes with a rotating disk that throws colored disco lights.

On Christmas day, Lagos has scheduled an execution. It seems like a fun thing to do, Wallen and her brother think. So they sneak out of the house, but there’s such a mob scene in the streets, they can’t get close enough to see anything. The next morning, Wallen opens up the newspaper to find a photo of the execution: a man hanging from a rope, his eyes wide open.

“What did the horrific violence signify?” wonders the writer looking back at her young self. “How did it relate to me?” What she remembers is a sense of dread: “anything could happen at any moment, and I had no way of knowing when or who or how.”

In When We Were Ghouls, the reader lives with Wallen through her precarious childhood as she faces odd customs, random violence, death, and a somewhat uncertain future. It’s a view that’s unsettling, but a reminder of how vulnerable it is to be an outsider.

___

Debbie Hagan is book reviews editor for Brevity and author of Against the Tide (Hamilton Books, 2004). Her writing has appeared in Harvard Review, Hyperallergic, Pleiades, Superstition Review, Brain, Child, Boston Globe Magazine, and elsewhere. She’s a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.