At three years old, Sandra Gail Lambert lay in a windowless room, in a plaster cast that covered her from chest to knees, healing from polio surgeries. Her mother would see her only one hour a day. The rest of the time, Lambert did nothing but listen to ambient noises and try to identify their varying sources. This left Lambert claustrophobic and determined never to be trapped again and to make the most of her abilities.

At three years old, Sandra Gail Lambert lay in a windowless room, in a plaster cast that covered her from chest to knees, healing from polio surgeries. Her mother would see her only one hour a day. The rest of the time, Lambert did nothing but listen to ambient noises and try to identify their varying sources. This left Lambert claustrophobic and determined never to be trapped again and to make the most of her abilities.

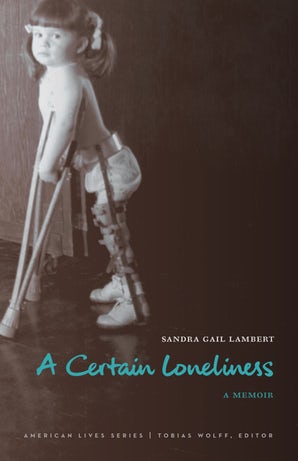

From cast to braces to crutches to manual wheelchair to power wheelchair, Lambert moves on becoming a nature lover, kayaker, photographer, and adventurer plunging headlong into rapids. In these beautiful, linked essays titled A Certain Loneliness (part of the University of Nebraska Press’s American Lives Series, edited by Tobias Wolff), Lambert portrays her life as one that rails against limitations and pushes steadily toward confidence and freedom.

She finds joy in a tight group of women friends, so enmeshed, “We can open the door to each other’s houses and yell a hello,” she writes. “Or we rush over in the middle of the night to be there, make coffee, or cry after bad news…. Sometimes we sneak in a dozen cupcakes, chocolate filled with cream cheese frosting, and leave them on the counter just because.” These are pure friendships without “qualifiers.”

The challenge comes when a new friend enters their circle. Sometimes the friend builds a ramp to her house; sometimes, she doesn’t. If the latter happens, Lambert knows “it’s going to go bad.” Without a bridge, she will never be able to leave surprise cupcakes and ultimately, “I will have to break up with her in my heart.”

The power wheelchair offers Lambert mobility, and yet it creates its own barriers. For instance, she’s about a head lower than everyone else. So, friends must remember to look down; otherwise, she will be left out of the conversations, handshakes, and the hugs she craves. Lambert creates some math to calculate potential opportunities for physical touch. For instance, if she’s going to a friend’s house, she can count on a hello hug. That’s worth about five seconds of contact. Three more hugs, pushes it up to twenty seconds. However, if she swings her body out of her wheelchair and onto the couch, she’ll rub shoulders and thighs on both sides with friends for two hours. That’s 7,200 seconds of touching.

It’s in the streams and woods Lambert finds real freedom. Getting in and out of the wheelchair and into her kayak, launching it, and then reversing the process requires complex maneuvers and calculated risks.

Alone in the Okefenokee Swamp, she sees snakes hanging from the low-hanging branches and the nose, eyes, and rugged back of an alligator. None of this scares her. Fear only comes when she can’t remember if she brought the hook she needs to get to the platform to get to her wheelchair that will take her back to her van. If she doesn’t have that, she’ll be stuck and doesn’t know what she will do. Fortunately, she brought the hook, and as the moon rises, she watches as “the sunlight sheens across the grasses and turns each patch of water into a pink pool.” The songbirds stop, and she hears the hoots of the first night owl. This fills her soul with hope, magic, and self-accomplishment.

As I read this, I reflect upon my eighty-eight-year-old father, who I’d recently took to a nature museum. Since he couldn’t stand for long, I placed him in a wheelchair. As I pushed it around, I saw the world quite differently. I noticed the museum’s railings were mounted at Dad’s eye level, the exhibits placed higher, which caused him to throw his head back and stretch to see them. Visitors darted in front of him, some standing in his line of sight as if he didn’t exist or was too old to matter. We skipped exhibits that were either impenetrable or where visitors were unwilling to let a wheelchair pass.

While Lambert’s memoir shows us one woman’s strength and courage in her battle to defeat fear, loneliness, and physical challenge, I’d like think this book offers more. It should make each of us question: do we build ramps for those differently able or do we simply ignore the problem and look away?

___

Debbie Hagan is book reviews editor for Brevity and author of Against the Tide (Hamilton Books, 2004). Her writing has appeared in Harvard Review, Hyperallergic, Pleiades, Superstition Review, Brain, Child, and elsewhere. She’s a visiting lecturer at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.