When my brother and I acted out as children, my mother threatened us with exile. If we fought, she said she’d drop us on our father’s doorstep. And if we were really bad, say, if we refused to eat our cheeseburger-flavored Hamburger Helper, she’d leave us with our maternal grandmother, Barb. She said she loved us, but if we couldn’t shape up she’d be left with no alternative. If we refused to be civil with each other or woke her up before noon on a Saturday morning or were disgusted by congealed fake cheese and greasy meat, clearly we didn’t love her or want to live with her. At least this is how I, as a seven-year-old, translated her adult-speak.

In my mind, being left with my father was equivalent to being left with someone who clearly didn’t want us since, my mother said, he refused to pay child support. I didn’t think I was assuming too much. After all, we never saw him. Who knows where we’d end up if left in his care? On the other hand, being left with Barb was far worse. She’d knock our heads together. We didn’t know how good we had it, my mother warned. Barb had beaten her so badly she couldn’t lie down on her back for a week. Rather than beat us herself, she’d leave it to her mother.

It turned out I had good reason to believe my mother would leave us. Once, when I was eight, she left us for six months with my best friend’s family. From there, we lived with my father for four months. I thought my brother and I had finally gone too far; we’d finally chased our mother away for good. I didn’t find out until later that we were suddenly homeless, and my mother couldn’t bear the thought of my brother and I sleeping in a freezing car with her that night. She’d had no other choice.

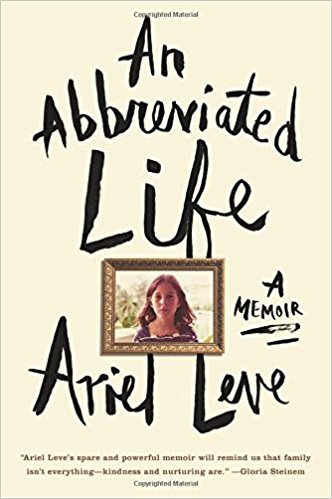

What becomes of children with unstable parents? This might be the central question of Ariel Leve’s 2016 memoir, An Abbreviated Life: A Memoir. In a conversation between forty-five-year-old Leve and her father, Leve’s father asks, “‘Why can’t you just beat those demons and destroy them?’” Leve responds, “‘You mean why can’t I just get over it.’”

Leve writes, “It’s illogical to him that I would be a thinking person who can’t control my thoughts.”

Her father goes on to say, “‘Or if you can’t get over it, then deal with it in a rational, sensible mature way. Which you’re capable of doing with other kinds of decisions.’”

The “why-can’t-you-get-over-it” question dogs some people. For others, like a novelist that Leve interviews, the experience of childhood abuse and instability is an exercise in pulling yourself up by your bootstraps, which Leve suggests, is “intolerant of any alternative.” Leve takes the opposite view with the novelist: “‘There are certain people who have been front-loaded with trauma that shapes who they are. They are disabled. Psychologically. And this does not make them victims. It makes them soldiers.’”

Leve seems to become a kind of soldier in her memoir. She recounts brief snapshots, memories with her mother. These memories are like individual bullets that whiz over her head: the time when her mother told her that when she was dead, Leve would be all alone because her father wouldn’t want her; playing a game called “Being Born,” in which Leve’s mother literally re-enacts young Ariel’s birth; the times when her mother told her that if Leve didn’t behave she’d have a nervous breakdown and end up in Bellevue or that she’d commit suicide. Leve ducks to avoid getting her head blown off, but she lives with invisible post-traumatic stress.

One therapist reveals that Leve likely has brain damage. “‘There are parts of your brain that did not develop the way they should have. And the way you function is a consequence,’” the therapist tells her. Leve writes that she’s incredulous, but she wonders, “how does a child build a foundation on quicksand?”

Ultimately, Leve discovers, in part, that children learn adaptive coping mechanisms that don’t often translate well into adulthood. For example, Leve discovers that because she’s protected herself “from feeling the horrible things,” she’s often numb to the good.

She has to learn to live differently with her damaged brain. Leve watches and learns from the young daughters of the man with whom she is in a relationship. In order to help them grow emotionally mature, she is careful when she speaks to them, allowing them to feel and express their full range of emotions so that they can learn how to control those emotions in productive ways. In juxtaposing her experience with those little girls, Leve’s memoir itself becomes a redemptive act of emotional freedom that allows her to remember the instability and trauma of her childhood as she gives herself the permission to simply feel. She writes, “We tell our stories to be heard. Sometimes those stories free us. Sometimes they free others. When they are not told, they free no one.”

__

Jennifer Ochstein is a Midwestern writer and professor who has published essays with Hippocampus Magazine, The Lindenwood Review, The Cresset, Connotation Press, and Evening Street Review. Like many other creative nonfiction writers, she’s working on a memoir about her mother, and she’s discovered it takes just as long to process that relationship as it has to live with it.