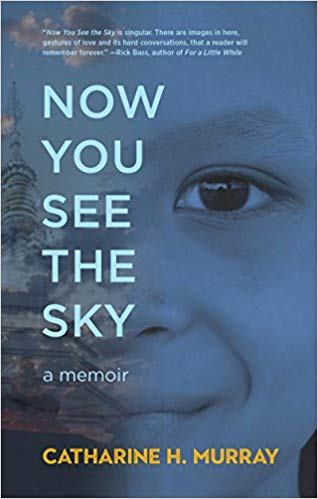

In the summer of 2012, I attended the Tin House Summer Workshop where Ann Hood read from, Comfort: A Journey Through Grief, her memoir about her daughter’s sudden death at age five. It was a hot summer night and people fidgeted endlessly to get comfortable. Hood’s words, so full of sadness but a testimony to love and hope, hushed the crowd. In the opening pages of Comfort, Hood provides rebuttals to all the well-meaning things people say to help someone deal with grief. Her friends give her other stories of loss and Hood says: “But none of them lost Grace. They do not know what it is to lose Grace.” Hood understands the power of telling one’s own story. Her new imprint, Gracie Belle, from Akashic Books focuses on stories of grief, loss, and recovery. The debut book, Catharine H. Murray’s memoir Now You See the Sky, delivers a gorgeously written memoir that burrows deep into the heart.

From the start, the reader knows that this family will suffer the loss of a child. However, the opening part of the book is about how Murray ends up in Thailand, finds love, and builds a life there. The beginning pages are filled with marriage, births, jobs worked, houses built, meals shared, prayers and rituals performed, leaving the reader feeling safe with the idea that we have complete control over our lives. Then there’s the diagnosis that Murray’s son, Chan, has terminal leukemia. It hits harder, just having read about all the life that has been conducted, and it serves as a powerful reminder that everything can change in a moment.

This is not an easy book, and not just because it concerns the death of a child, but entire sections spare no detail on the suffering and mental anguish that comes with cancer. Murray puts everything on the page—the physical suffering, the exhaustion of being a caregiver, the frustration of not knowing what to do, the ways in which siblings sacrifice, the emotional burden. It is one of the most open, honest, and raw accounts I have read, and Murray offers us her thoughts uncensored:

Because I was holding a small, crying skeleton of a boy all day, the healthy, happy boys were a double delight to me, if not to Chan, who cried when he watched little Than run joyfully as fast as his thick legs could carry him. And in some terrible way, they offered me a kind of assurance. Well, if Chan dies, I will be left with these very healthy boys.

The reality is that there is no clear, direct path when making decisions about the fate of another person, especially a child. Murray brings these struggles to light with no sugar coating. She agonizes over whether she should tell Chan that he is dying. She wonders if she should have given in to the treatment plan prescribed by the hospitals, which is to say his goodbyes and go on morphine until he dies. Murray’s courage in taking care of her child away from doctors and hospitals is tremendous. She does this to give him a chance at living with his family, on the land he loves, and to leave open the door that there is a possibility he can also heal:

Fresh, tender fiddleheads gathered from the edge of the stream below her sprawling garden; wild pennywort, glossy green faces like giant shamrocks, the plant we pressed to make the bitter juice that Chan had learned to swallow, believing what we hoped, that it might beat back the cancer; balls of sweetened sticky rice stuffed with black bean paste and coated with flakes of coconut, all raised and harvested by Tong and Cam from the land they worked and loved.

Coming from a western sensibility of how we handle terminal illness and death, there are parts of this book that initially were hard to understand. In the United States, elderly go into nursing homes, the sick go to die in hospitals and doctors oversee their last days, our funerals are structured and packaged affairs that seem to try to distance us from death. Chan dies at home in the arms of both parents. The family gathers and stays with the body for days, moving to the temple for cremation. Then they collect some of Chan’s ashes and pieces of small bones. There is a communion with the body and spirit, and intimacy with death and a recognition of what has passed that forms a natural pathway to acceptance and healing.

Dtaw and I untied the plain cotton cloth that held the ashes, poured the bone shards from the jar onto them, and covered it all with the flower petals. Cody and Tahn and Jew helped Dtaw and Cam and me lift the bundle over the side to tilt the last tangible elements of their brother into the swirling brown water. The gray dust of his ashes floated and shimmered in the sun on the surface before the water swallowed them.

Even readers who have been fortunate enough not to suffer a devastating loss like Murray will still learn much from her story. After reading, I revisited my thoughts on what is a good death, how we treat the dying, and the importance of our memories. I also learned about a sweet, little boy who lived in the mountains of Thailand and loved horses. Chan’s mother still feels his presence and remembers him. This reader now carries Chan’s story too, and it is an honor. I’m thankful that Catharine H. Murray had the courage to tell her powerful and illuminating story and that Ann Hood gave it a way to reach others.

___

Emily Webber was born and raised in South Florida where she currently lives with her husband and son. Her stories and essays have appeared in The Writer, Five Points, Maudlin House, Fourth & Sycamore, and elsewhere. She’s the author of a chapbook of flash fiction, Macerated, from Paper Nautilus Press.