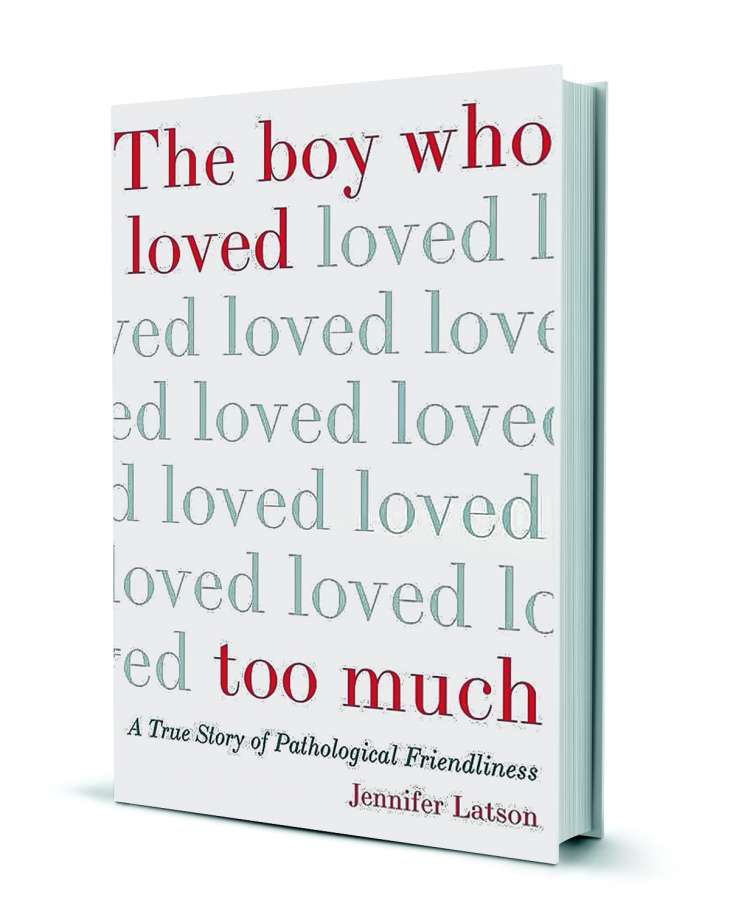

Gayle D’Angelo was worried about her son. While his classmates in daycare were learning to walk and talk, Eli would simply coo and smile, then hold out his arms for a hug. “He catapulted himself into the arms of a schoolmate’s mother one day and climbed into the lap of a burly man at a shoe store the next,” writes Jennifer Latson in The Boy Who Loved Too Much: A True Story of Pathological Friendliness.

Gayle D’Angelo was worried about her son. While his classmates in daycare were learning to walk and talk, Eli would simply coo and smile, then hold out his arms for a hug. “He catapulted himself into the arms of a schoolmate’s mother one day and climbed into the lap of a burly man at a shoe store the next,” writes Jennifer Latson in The Boy Who Loved Too Much: A True Story of Pathological Friendliness.

At the suggestion of another parent, Gayle decided to look up a disorder called Williams syndrome. She began to read, then leaned over a trashcan and threw up.

In this debut title, Latson introduces us to Eli, Gayle, and a genetic disability whose most distinctive symptom is a complete absence of social reserve. “[W]hat would it be like to go through life this irremediably vulnerable, biologically unable to peel your heart from your sleeve and lock it safely inside?” she writes.

Latson spent three years shadowing Eli and Gayle (their names have been changed), starting when Eli is eleven. Her portrayals––subtle, complex, and unexpectedly funny––reflect this. “It was easy to fall in love with Eli,” she writes. I fell in love with him too: he’s a joyful, open-hearted boy who remains blissfully unaware of his shortcomings. Latson’s depiction of Gayle––a single mother of surprising, almost unimaginable strength––is rich and nuanced. Before she ever hears about Williams syndrome, Gayle is known to friends and family as an outspoken rebel, a fan of hard-rock concerts and horror-movie conventions. After Eli is diagnosed, Gayle trades in her heavy eyeliner and purple lipstick for sweater sets. She decorates the apartment with pictures of Cookie Monster, and delights Eli by dangling twirly, paper decorations from the doorframes.

Gayle’s ability to subvert the trappings of her old life was particularly striking to me. Before I had my first child, I feared, secretly, that the simple act of having a baby would somehow cause me to morph into an unrecognizable version of myself: would I spend my free time placidly pushing a stroller through the mall? Banish the family pets to the basement? Stop shaving my legs? In Gayle, Latson shows us someone who’s realized she has to change. To advocate for her disabled son, she must present a calm, composed version of herself to the world. The rebel and the fighter––needed more than ever––must stay below the surface, hidden along with her tattoos and ear discs.

Latson delves into the genetics of Williams syndrome, examines the prospects for gene therapy, and places the disorder in its historical context. It’s a relatively rare condition, she explains, accompanied by bewildering symptoms. People with Williams––often recognizable by their elfin-shaped faces––tend to be verbally proficient and deeply affected by music. They have difficulty with spatial concepts (making it hard, for example, to draw a simple figure) and are often plagued by anxiety, phobias, and fixations. (Eli, not atypically, is obsessed with industrial floor scrubbers.) But most notable is their highly social, effusive personality. Historians surmise they may have served as jesters and fools in the courts of medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Latson shows Gayle and Eli facing all kinds of new situations: some of the book’s funniest and most touching scenes take place at a Williams syndrome camp, where Eli finds himself surrounded by uninhibited, exuberant kids just like himself. But it’s the onset of adolescence that poses the greatest peril. The stakes here are high: Eli must learn certain social skills so that he can navigate the complexities of adulthood, and “whether or not he could do so would mean the difference between being an active member of the human tribe, or living life on the margins, facing an especially acute loneliness.” By age thirteen, Eli still sings the Cookie Monster song, but his hormones are surging out of control. Once-innocent hugs are now directed toward large-breasted women: “Eli was a stage,” writes Latson, “on which puberty played out for all to see.” Gayle enacts a strict no-hugging policy: it’s handshakes and high-fives from now on. But Eli will not––cannot––comply.

Latson does a delicate dance here, illustrating everyday moments that are often mortifying for Gayle, hilarious to the reader, and which would be embarrassing for most people––but not Eli. She depicts him in all his earnest awkwardness, with great affection and not a hint of condescension. The book closes as Eli begins high school. I, for one, wish I could have stayed with Eli and Gayle just a little longer.

__

Tucker Coombe writes about nature and education from her home in Cincinnati. Her work has appeared most recently in The Rumpus and Los Angeles Review of Books.