Bear with me. Grief is difficult to explain, difficult to experience.

Bear with me. Grief is difficult to explain, difficult to experience.

The first time I saw death was in the porcelain face of a 3-year-old boy, on the day I turned twelve. He lay in his small casket at the head of a stuffy room filled with moanings and whisperings—his own high-pitched laughter so clearly absent. My body couldn’t experience this new sensation all at once; it came in jolts.

His face was less round, his lips unnaturally red, the tender skin of his eyelids a dangerous blue. Who is that boy? my mind asked. He was unrecognizable as my friend, the little boy I loved.

~

With grief comes unspoken rules, we alter the way we communicate. Often, memories are shared in an offbeat staccato. The grieved look off, unfocused on the present with its unprocessable pain, attempting to make sense of these dangling bits of past life. There is difficulty in maintaining posture, upright attitude. Breakdown is complicated.

How much more difficult is it if the deceased was your mother?

How much more complicated is the grief, the explanation, the piecing together, if that mother was a stranger before she chose to mother you?

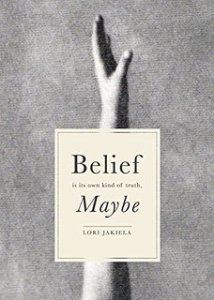

Lori Jakiela explores this in her memoir Belief Is Its Own Kind of Truth, Maybe. This is a story about grieving the deaths of her adoptive parents, grieving the twice-rejection from her birth mother, and embracing her own motherhood while still working to define it. To say she’s sharing something private and vulnerable is not saying enough of this complexly-arranged and deeply-probing memoir. Yet, these highly personal details of Jakiela’s life aren’t confessionals; rather they are examinations of what it means to accept your own story.

When she writes about her birth mother, Jakiela uses informed fictions to recreate what might have—what must have—happened leading up to her adoption. She imagines the story of a young 1960s Irish-American woman, pregnant out of wedlock, raised by an often abusive father, hiding in a sister’s closet, giving up a child to avoid giving up a secret.

When she describes her relationship with the parents who adopted her, she describes a complicated raising not so dissimilar to those of us who were not adopted. There is the moodiness, a discontent, filled with snappy remarks and misbehaviors. In the extended family, she was one of two adopted children often seen as outsiders, bookends in the family photos.

Jakiela never fully admits it, but the choice of love is always present in her story. Her parents chose to love her, while her birth mother chose not to. Yet, this conflicts with how she describes her own mothering: an intense, worry-driven, awe over her two young children—where tone of voice, quality of interaction, and time spent are all choices, but where mother-love exists without permission and is heavy with danger.

“Family,” she writes. “The word is a mantra, a totem, a skyline that goes on forever until it drops off at the end of the world.”

~

At 12-years-old, through grieving my little friend, I faced the confusing act of naming my attachment. An emotion I’d never felt before pushed out against my ribs, up through my throat. At his coffin, all I could feel was the uncontrollable and solid loss. I choked on it, while my mother led my suddenly-loud body away from the other mourners.

Hours later, at the wake, I sat in a dark corner out of embarrassment, trying to keep myself unnoticed as strangers shifted around a buffet table. Who was I to grieve this child? I tried to understand.

The little boy’s mother found me and took my hands. She knelt down and looked into my eyes. She thanked me for loving him. She said I was his little second mother. She let me share in her mother-grief, and, because of this, I found a grief of my own.

~

Grief is a search. For stability, for acceptance. Jakiela’s structure reflects the scatterings and incoherence of grief. She uses fragments. She weaves.

“Splice:” she explains, “to bring together strands, to interweave, to join segments of DNA.” She doesn’t simply tell us the story of her adopted life or her parents’ deaths or her search for her birth family. Instead, she lets it grow, with a root system connecting us to the scattered narrative.

She uses single words, images, ideas—a knife blade, a color, a need—overlapping and echoing throughout the memories often written in the present tense.

“I’m holding a knife.” Jakiela writes of a moment when her grief emerges in the mundane. “I’m trying to slice a bagel in two. I’m not thinking about the knife. I hold the bagel in my palm and saw the blade down into my skin.” Only then does she remember her mother’s consistent instruction to cut away from herself. “I pull my palm back and inspect the ragged cut right between the heart and life lines.” The implications are not lost in the words here. “It’s not deep,” she writes, “but still.”

When Jakiela talks of grief, I feel in my own body the memory of my own losses. “I’m a mime in a box. I’m an expired coupon, an empty slot machine with its bells smashed out,” she writes. “I do not call this what it is: grieving.”

Yet, this story is more than an adoption story, an abandonment story, a grief story. It’s a story of moving on. In quiet, rhythmic lines arranged on the page like landscapes riddled with cliff edges, Jakiela shows us how to believe we are worth the jump, the leap we need to move forward. That is the ultimate truth in this book: to believe we are worth it. And accepting that is its own kind of truth, too.

Maybe.

__

Ellee Prince is the assistant editor of New Ohio Review. With a background in magazine journalism, an obsession with witty fiction, and a closet collection of poetry since age seven, she is now writing (and a master’s student in) creative nonfiction at Ohio University. Exploring issues of home, health, and connection, her work has appeared in Proximity, Alimentum, Southeast Ohio, Ohio Today, Outdoors Northwest, and elsewhere. She is currently working on a memoir, chronicling her 24+ childhood homes across the country.