“Nothing behind me, everything in front of me, as is ever so on the road,” wrote Jack Kerouac in his 1957 novel On the Road giving us a metaphor of postwar America that we would live and die with for decades. I felt it myself some years ago. Having just moved to Chicago’s South Side, I stood at the window of a fifteenth floor apartment, looking westward towards the unforgiving horizontals of the landscape. This flatness was strange for someone from the Northeast used to hills and shorelines. The evening light dimmed and the streetlights came on, and I followed their sparkle toward their vanishing points in the dark horizon of the unknown, which was how I was feeling on my arrival to the city. Of course, after On the Road, it’s hard to see a road as just asphalt and concrete.

“Nothing behind me, everything in front of me, as is ever so on the road,” wrote Jack Kerouac in his 1957 novel On the Road giving us a metaphor of postwar America that we would live and die with for decades. I felt it myself some years ago. Having just moved to Chicago’s South Side, I stood at the window of a fifteenth floor apartment, looking westward towards the unforgiving horizontals of the landscape. This flatness was strange for someone from the Northeast used to hills and shorelines. The evening light dimmed and the streetlights came on, and I followed their sparkle toward their vanishing points in the dark horizon of the unknown, which was how I was feeling on my arrival to the city. Of course, after On the Road, it’s hard to see a road as just asphalt and concrete.

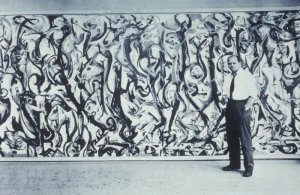

Riley Hanick’s Three Kinds of Motion: Kerouac, Pollock, and the Making of the American Highways navigates the concrete and the metaphorical in a mesmerizing way. “The highway replaces space for motion,” he writes. This claim gives shape to his meditations on the ways motion (and emotion) transforms space, be it the landscape, a canvas, or the scroll of Kerouac’s manuscript. It is Hanick’s native Iowa with its flat fields and sloping hills that gives the book its physical and mental geography. While living in Boston after college, his relationship ends and his office job dims; he moves back to Iowa, into his parent’s basement, and starts painting houses. At the University of Iowa Museum of Art, he encounters Jack Kerouac’s original manuscript for On the Road, a 120-foot long continuous scroll. In that same museum, he also finds Jackson Pollock’s 1943 painting Mural, a wall-sized rectangular work that, in Hanick’s wonderful words, holds a “frenetic bluster” of composition. Peggy Guggenheim had commissioned it for her New York townhouse on East 61st Street. He imagined it as a “stampede of every animal in the American west.” A few years later, Guggenheim would give the painting to the University of Iowa—a throwaway gesture. Why she did this is not clear. Hanick speculates, but the reason seems unimportant.

The third subject has little to do with art, or rather less so: Eisenhower’s creation of the Interstate Highway System, a feat of governmental vision that eventually created a network of roads connecting the rural with the urban, the north to the south, and the flatness with the mountains. This network of highways is Hanick’s more compelling subject, offering a historical reality that guides his reflections on postwar American aesthetics with their fecundity and tragedy. Consider this: Pollock crashes his car into a tree on a road in Long Island in 1956, killing himself and one of his passengers just months after Congress passes the Federal Highway Trust Fund. A year later, Viking Press published Kerouac’s On the Road. These faint lines between events make Hanick’s book so strange and engrossing.

Hanick’s meditative approach swirls you into a lingering conversation of facts and reflections, between personal, historical, and biographical. We learn the process of concrete making, gossip about Peggy Guggenheim’s affairs, the Chelsea Hotel rendezvous between Kerouac and Gore Vidal where “Jack blew him, was on bottom, and maybe slept on the bathroom floor.” We learn of Eisenhower’s painting habits, Pollock’s early career in the WPA, the Iowan floods that threatened to destroy Mural, the debates and plans that shaped the Eisenhower memorial in Washington D.C., and that Pollock’s mother dressed him in handmade clothes, “in gingham and chambray and fine silk pongee.”

It’s easy to get lost in the reading experience. Holding on to the intersections of highway history and Pollock’s canvases and Kerouac’s scroll, and the many lives and events that he crosses through is not always easy. The book flirts with you not by promising an end, some destination or arrival, but rather with the pleasure of Hanick’s fragments of reflections, crisscrossing place and time with ease, rendered with lyrical play and precision, never situating you anywhere solid for very long.

Hanick writes near the end of the book, our highways “remain a fixture in our cinematic dreams” as we hold on to the persistence of concrete. But then he reminds us how easily we ignore the fact that “it is only water that will be required to quickly rip” our roads apart. Set within history and experience, Hanick gives us a meditation on longing, even for those things that seem so certain.

__

James Polchin teaches in the Liberal Studies program at New York University