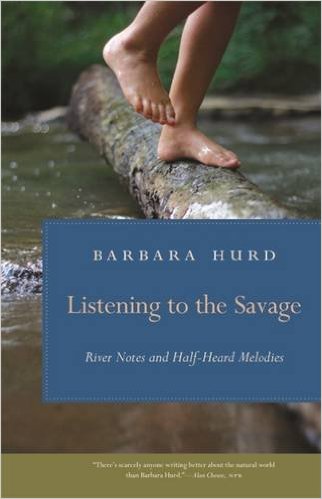

About half-way through Barbara Hurd’s latest essay collection, Listening to the Savage: River Notes and Half-Heard Melodies, I find myself splayed across a granite boulder in the middle of the small river that runs through my backyard in rural Vermont. Obviously, I am listening for crayfish. An avid river watcher, I confess that until reading this beautiful, brilliant book, I had not considered the role of river listener, or river monitor as Hurd calls herself, pointing out that monitor derives from the Latin monere, which means to warn or advise—even to remind or teach, according to my old Latin dictionary. From my back porch, I often eye the river’s movements, its patterns, its shimmer and light; I watch for deer, wild turkeys, ospreys, foxes, bald eagles, and the occasional Great Blue Heron. Recently, in the shallows near the yard, a few kids appeared, pants hiked up over their knees and buckets swinging from their elbows. “What are you guys looking for?” I hollered from the porch. “Mudbugs,” one called back; “ten so far.” At fourteen, I was a budding scientist who won a National Science Foundation scholarship to the University of New Hampshire’s month-long Mathematics and Marine Science Program, but I’m a long way from fourteen, and content now to marvel at nature through my camera lens or binoculars. And yet, with stirring pathos, Listening to the Savage, has called me back to the river; more urgently, the book has summoned me to listen, “to turn my ear, that lonely hunter, and put it closer to the ground.”

About half-way through Barbara Hurd’s latest essay collection, Listening to the Savage: River Notes and Half-Heard Melodies, I find myself splayed across a granite boulder in the middle of the small river that runs through my backyard in rural Vermont. Obviously, I am listening for crayfish. An avid river watcher, I confess that until reading this beautiful, brilliant book, I had not considered the role of river listener, or river monitor as Hurd calls herself, pointing out that monitor derives from the Latin monere, which means to warn or advise—even to remind or teach, according to my old Latin dictionary. From my back porch, I often eye the river’s movements, its patterns, its shimmer and light; I watch for deer, wild turkeys, ospreys, foxes, bald eagles, and the occasional Great Blue Heron. Recently, in the shallows near the yard, a few kids appeared, pants hiked up over their knees and buckets swinging from their elbows. “What are you guys looking for?” I hollered from the porch. “Mudbugs,” one called back; “ten so far.” At fourteen, I was a budding scientist who won a National Science Foundation scholarship to the University of New Hampshire’s month-long Mathematics and Marine Science Program, but I’m a long way from fourteen, and content now to marvel at nature through my camera lens or binoculars. And yet, with stirring pathos, Listening to the Savage, has called me back to the river; more urgently, the book has summoned me to listen, “to turn my ear, that lonely hunter, and put it closer to the ground.”

Listening, Hurd suggests, goes beyond observation and places the listener within the world: “If, as the ancients say, careful seeing can deepen the world, then careful listening might draw it more nigh. The eyes, after all, can close at will; we can avert a glance, lower the gaze, look elsewhere. But the ears, those entrances high on our bodies, doubled, corniced, aimed in opposite directions, can do nothing but remain helplessly open” (2). If Listening to the Savage is a call to listen—to reclaim a sense perhaps atrophied by a culture of distraction and ubiquity—it is more siren call than polemic, for the author implores herself, as much as the reader, to do the difficult work of fully inhabiting the world, the mind, and the body. In the essay, “Practicing,” Hurd describes her efforts at such presence—whether monitoring the river or practicing the piano:

I’m trying to see what it’s like, in other words, not just to practice, but to have a practice. I’d like to reach a point where the choice to sit at the piano or go for a walk is less and less a choice and more and more simply what I do. Progress is gratifying, of course: a permanent ban on drilling matters, and a decent piano performance might be fun. But until then spending a little time every day with music and wandering the watershed with an ear to the river might eventually become a habit, like something one wears, not so much a garment, but skin, part of the body. Habit then might deepen to inhabit, to dwell in a place, maybe even a life. I’d like that.

Hurd’s seeking is a kind of devotion to listen to the world as it is, not for harmony or for discord—but for both. “Here’s my prayer,” she writes in “The Ear Is a Lonely Hunter,” the book’s rousing opening essay:

Help us to listen to the sounds—fragmented, atonal, melodic, diminished, augmented—of our own lives and of the myriad lives among us: cricket trill, beaver whack, birdsong, snake hiss, donkey bray. Give me the voiced morsels of this child [her granddaughter, Samantha] (‘Meemi, sometimes I get dark messages from my eyes’), unconducted love songs begun in the cattailly edges of a pond and the bellowy burp of bullfrogs. For this is the grounding, the sounding, things as they are, for now and for now. Amen.

At the end of the essay, Hurd explains how vision “is deepened by listening, especially if the ear has turned from any wishful music of the spheres and heard, as if for the first time, the whoosh of wind in the trees or the cry of a red-tailed hawk.” It calls to mind Susan Sontag’s entreaty in her essay, “Against Interpretation,” in which she argues that the overproduction of art has blunted a kind of collective, cultural sensory awareness. Sontag writes, “What is important now is to recover our senses. We must learn to see more, to hear more, to feel more.”

Barbara Hurd has been awarded three Pushcart Prizes, the Sierra Club’s National Nature Writing Award, an NEA Fellowship in Creative Nonfiction, and a 2015 Guggenheim Fellowship; this new book marks a stunning achievement in an already remarkable oeuvre. The essays in Listening to the Savage offer up rich explorations of literature, epistemology, love and family, science and place, and even of attentiveness itself. The meanderings of the author’s mind—whether quibbling with Thoreau or poring over her father’s letters from his 17-month internment in a German POW camp—often wend along those of the book’s titular river, the Savage in Western Maryland. In prose that is stunning, searching, precise, querulous, and revelatory, Hurd demonstrates how attentiveness can be the writer’s best instrument. Such is perhaps the larger hypothesis of the book, which calls upon the reader to listen deeply, whether for its own sake or that of art or the planet.

This was how I came to commune with the crayfish who seemed to be sunbathing on the rocks exposed by an unusually-parched riverbed this summer, as New England experienced one of the worst droughts in its history. Listening to the Savage prompted me to attune my hearing in much the same way that Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek made me see the act of seeing itself. You know that old saw that goes something like fish can’t see the water they swim in? I had no awareness of my own hearing, no clarity of sense I realized, as I sat on the rock waiting for the crayfish to speak. I didn’t know how to listen to crayfish, of course, so I listened intensely for many minutes, pleading with my ears to work, and for my auditory senses to tune into some deeper source. I could hear the river, the cows across the way, cars buzzing by, but no crayfish. Perhaps they were soundless creatures, like arthropodal mimes, I thought, climbing up the riverbank and back toward the house, but no, I had read about the clicking sound—had listened to a recording online of a stridulating crayfish clicking furiously around an underwater rock cave that made me imagine crustacean pinball. I had been bitten by a kind of mudbug fever, but more than that, I was mimicking the exquisite listening that Hurd performs in the book; I was seeking connection. I began to comb maps of the White River Watershed, looking for mile markers, like those that mark certain chapters in the book. If I found mile 11, for example, of my own river, perhaps I might locate the heady vibrations of Hurd’s prose: “Want to deepen your nostalgia? Imagine you’re a river that believes in once upon a place.” Possessed with an idea that the waters of my river might somehow mingle with Hurd’s Savage, in some forgeable intersection, I began to trace the two rivers on separate maps. Alas, our rivers don’t meet, at least not on the watershed maps. The Savage runs into the North Branch of the Potomac, then into the Potomac, then into Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, while the White River runs into the Connecticut, then into Long Island Sound and the Atlantic some three-hundred miles northeast. When I began looking at maps of ocean currents and the path of the Gulf Stream, I realized I had gone too far; I didn’t need a map to tell me that I was connected to this book.

In essays that weave modes of lyricism, narrative, research, and social commentary, Hurd takes the reader on a sublime listening journey. Whether recording her granddaughter’s quirky wisdom (“Some dreams you tell and some you don’t”), or raindrops while channeling a spadefoot toad, or the dehiscence of fern annulses when they “all start snapping like a legion of catapults,” or the interior alert that called the author out of an early marriage, Barbara Hurd’s voice sings. “I don’t know why certain sounds—wind chimes on the back porch, loon calls, that big owl’s silence—can open an ache in me,” she writes. “I only know—at least for the moment—that today’s steady hiss of snow on snow works like a psst in my ear, making the mundane both more mundane and less: mundus, after all, means the world.” In the essay, “To Keep an Ear to the Ground,” Hurd writes, “Sometimes when I put my ear to the ground, I make my own arbitrary rules: No listening for anything I might expect. No listening for anything that has a plan for me. No listening to anything that knows I’m listening. No pretending to listen to what bores me utterly.” I realize that my efforts to listen to the basking crayfish were hampered by two things. First, I was pretending. Second, I should have been listening and watching, for if I had taken a closer look, I would have seen that the brittle, desiccated creatures were not sunbathing at all, but dead. Next time, I’ll turn away from wishful music, put my ear to the ground, and listen for whatever the world brings. To hear things as they are, I’d like that.

___

Alexis Paige‘s work appears in multiple journals and anthologies, including Fourth Genre, The Pinch, The Rumpus, Pithead Chapel, and Brevity, where she is an Assistant Editor. Her essay,”The Right to Remain,” was named a notable in the 2016 Best American Essays anthology, was featured on Longform, and nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her first book, Not A Place on Any Map, a collection of lyric essays about the emotional terrain of trauma, won the 2016 Vine Leaves Press Vignette Collection Award and will be published in early December. She writes from a converted farmhouse pantry in rural Vermont, where she lives with her husband, and their two dogs, Jazz and George. Visit Alexis online at alexispaigewrites.com.