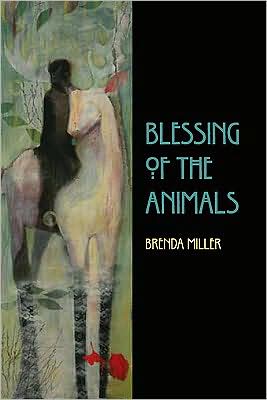

Eastern Washington University Press, 2009

Eastern Washington University Press, 2009

“The dogs are barking. All over Mexico, it seems, dogs are barking, and its 3 a.m. and a crescent moon hangs low in the sky.”

With this simplest of details, the opening to one of Brenda Miller’s marvelous essays, I’m transported back to San Miguel de Allende, a cobblestone and cathedral town filled with donkeys, street vendors, and American ex-pats in Mexico’s mountainous bajío region, where I had the good fortune to spend four weeks last summer. I remember those dogs, and I remember roosters crowing all through the night, too impatient for dawn.

For me, nothing beats lying awake in bed, with the window open, in a foreign land, breezes rustling the curtains, distant shouts carrying on the wind. Nothing serves better to make me feel that I’ve been to a place. The same with walking past an open window in some new neighborhood — a tucked-away corner where people raise their children, tie their dogs to tree stumps, hang their laundry on a line —and smelling someone’s dinner on a stove. If I get a glimpse of a woman in her apron standing in the kitchen, a large wooden spoon stirring the pot, all the better.

Which is why I’ve never understood people who spend five days locked behind the walls of an “all-inclusive” resort or who limit themselves to familiar restaurants and the tourist-approved, artificial streets of Cancun. I don’t want a hermetically sealed high-rise Hilton when I’m trying to experience an unfamiliar culture. I want street tacos, people’s gardens, and dogs. Barking dogs.

Blessing of the Animals, Miller’s second essay collection, is not about tourism. Or about dogs (though they show up again and again, always in welcome ways). Instead, this book is about a life lived with eyes and ears wide open, a thoughtful woman’s mindful path. Miller is a tourist in search of authenticity, but she is traveling her everyday life, examining the smaller moments, fully understanding that there is usually more truth to be found in the routine than in the extraordinary.

In Miller’s hands, of course, the commonplace often becomes somehow extraordinary, through the elixir of her lyricism, her exquisite sentences, and her unflinching honesty. This is what I truly love about Miller’s writing, whenever and wherever it appears. (Occasionally, here and here in Brevity.)

Stanley Kunitz has said that the writing of poetry would be easy “if our heads weren’t so full of the day’s clatter. The task is to get through to the other side, where we can hear deep rhythms that connect with the stars and the tides.”

Miller patiently waits out the daily clatter until she hears those deep rhythms, and then she shares the tidal murmurings in these fine, finely-tuned essays.

That’s probably what the barking dogs were trying to tell us.

—

Dinty W. Moore is the editor of Brevity.