For years, I wanted to be a foreign correspondent. I watched Jennifer Connelly’s sultry, savvy character on Blood Diamond getting tips from dangerous insiders in exotic places, and longed to be her. It seemed so thrilling. Glamorous, even. I procured a job covering commodities in Mexico at the height of the country’s drug war violence. But after several encounters with death, I developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Still in my twenties, I wondered how so many sustain this lifestyle. I wasn’t even covering the drug war.

For years, I wanted to be a foreign correspondent. I watched Jennifer Connelly’s sultry, savvy character on Blood Diamond getting tips from dangerous insiders in exotic places, and longed to be her. It seemed so thrilling. Glamorous, even. I procured a job covering commodities in Mexico at the height of the country’s drug war violence. But after several encounters with death, I developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Still in my twenties, I wondered how so many sustain this lifestyle. I wasn’t even covering the drug war.

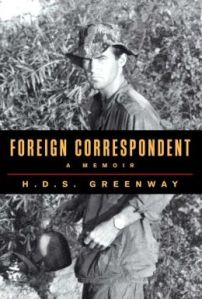

Veteran war journalist H.D.S. Greenway’s vivid memoir Foreign Correspondent explores a lifetime of experience reporting on bloodshed in Vietnam, Cambodia, Israel, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and elsewhere. With occasional quirky humor to offset the gravity of the horrors, Greenway skillfully sketches his coverage of some of the 20th century’s most important moments, using his collection of tattered, dirt- and blood-stained notebooks. He suspects he has “a touch” of PTSD, but unlike his father, who became distant and depressed after fighting in the Pacific War, and committed suicide in old age, Greenway managed to preserve his quirky lightheartedness.

At the beginning of his career, Greenway was fueled by a romantic illusion that he attributes to Hollywood and Ernest Hemingway novels. He notes that the suicide of his literary idol mirrored his father’s—a shotgun, a narrow space. He doesn’t address the irony of his choice of hero, but he recognizes his initial naïveté. Greenway recalls feeling invincible in Vietnam.

“My first reaction to getting shot was one of indignation,” he writes. “This wasn’t supposed to happen to me!”

I sympathized. The invulnerability illusion, the shock of its shattering—rites of passage, I suppose. Greenway focused on learning survival tricks. In Vietnam, he left his boots on while sleeping in case he had to run for his life. In Cambodia, if his presence in a town didn’t attract swarms of curious children, he knew it was time to turn around.

But he could not avoid witnessing the carnage. He was there to chronicle it. To this day, Greenway has nightmares about the children he saw torn to shreds.

“No movie has ever really shown what high explosives can do to human beings,” he writes.

For a while, he awoke in the middle of the night to the smell of dead bodies. Six of his friends died in the Indochina wars alone. More than seventy journalists were killed.

Surely, Greenway’s sense of humor was a source of his capacity for endurance. As other correspondents agonize about how to get out of Baghdad amid Gulf War chaos, Greenway buys a silver Aladdin’s lamp and tells his friends, “I have found my way out.”

It wasn’t just missiles and bullets Greenway had to worry about. Before the Internet came along, he recalls getting the story into an editor’s hands “could be more daunting and sometimes more time-consuming than either the reporting or the writing.”

Why did he—and countless other foreign correspondents—tough it out? Greenway captures the essence of his career’s enduring appeal when writing of Vietnam: “The war was all we reporters thought about in those days, and there was a certain comfort in that. None of the petty stuff of ordinary life concerned us.”

He’s referring to the satisfaction that comes from knowing one’s work is important—that life isn’t being wasted, even if it’s being risked. A crucial feeling indeed.

Ultimately, Foreign Correspondent is a meditation on the United States’ tendency to meddle in foreign conflicts. Greenway is critical, but doesn’t think isolationism is the answer.

That tendency was responsible for both Greenway’s illustrious career and the trauma borne of witnessing humanity’s most nightmarish acts. Although I wished he had delved more deeply into how he coped with the latter, perhaps the insight is implicit in the silence. It represents a capacity for distance I do not share and cannot yet emulate.

Also noteworthy is the intensity of Greenway’s love for his wife, evident throughout Foreign Correspondent. More than fifty years after stuffing a competitor in a car trunk to get to her, Greenway gives her the last word in his memoir. “You need to end this now,” she tells him. He dedicates the book to her.

Perhaps the key to the sustainability of the foreign correspondent’s tumultuous lifestyle is as simple as that: true love’s anchoring power. It is not for nothing that Hemingway wrote of his first wife in A Moveable Feast: “I wish I had died before I loved anyone but her.”

____

Jean Guerrero is an award-winning freelance multimedia journalist pursuing an MFA in creative nonfiction from Goucher College. Her work has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Seattle Times, Las Vegas Sun and other publications. She was one of the first reporters chosen to participate in Beacon, the innovative, subscription-driven journalism platform, at beaconreader.com/jean-guerrero.