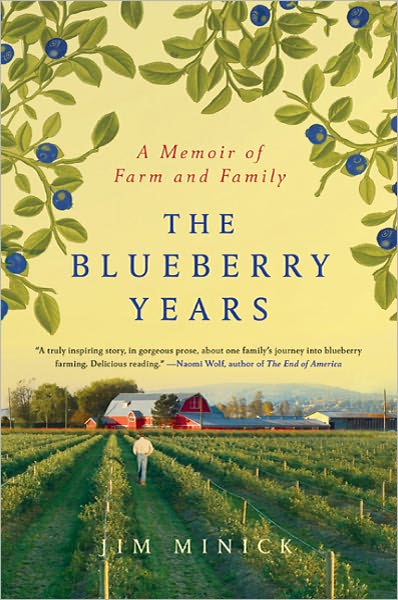

St. Martins Press 2010

To earn cash, Thoreau famously hoed a two-and-a-half-acre field one summer—seven hours a day “making the earth say beans instead of grass”—but thereafter planted only a garden. As he tartly observed in Walden, “The farmer is endeavouring to solve the problem of a livelihood by a formula more complicated than the problem itself.”

To earn cash, Thoreau famously hoed a two-and-a-half-acre field one summer—seven hours a day “making the earth say beans instead of grass”—but thereafter planted only a garden. As he tartly observed in Walden, “The farmer is endeavouring to solve the problem of a livelihood by a formula more complicated than the problem itself.”

Jim Minick and his wife, Sarah, learned this lesson during twelve years spent growing blueberries on their Appalachian Virginia farm. They hoped to supplement Minick’s university teaching and to allow Sarah, a schoolteacher, to stay home. In The Blueberry Years: A Memoir of Farm and Family, Minick tells how they cleared two-and-a-half acres and made them say blueberries. Grubbing out tree roots and planting 1,000 bushes staggered the couple, then in their late twenties. After developing a thriving, certified organic, pick-your-own business—any one of those elements a triumph—they saw that they needed at least four times as many plants to make money. But propelled by an evergreen American dream, they couldn’t have foreseen how much raising their crop would cost. Or how long and hard they’d work.

A neighbor, contemptuous of their organic efforts, lets fly with tobacco juice and jibes. Farmer Joe has actually made his living for forty years by conventional methods, lately with a you-pick strawberry patch. He’s a fun character, and Minick cherishes him in the book as in life. The couple’s struggles to find a larger community—in rural churches and a hippie compound—are poignant. They do better among their own customers; Minick’s picker portraits are among his book’s most appealing threads.

Thoreau, not content with being farming’s severest critic, was tough on writers, demanding “a simple and sincere account,” always harder than it looks. In this, Minick, a poet and essayist, excels. His memoir tells it like it was: root, branch, fruit, sweat, disastrous freeze, errant joys. He made a good life, if not a good living, at small-scale farming. When the Minicks surprise everyone, even themselves, by buying a bigger place, they plant only a garden. And blueberry bushes. It’s a lifestyle farm, but it yields what they crave, birdwatching and hiking along with food to eat and share.

Revisiting his first dream, Minick finds his lovingly tended acreage in ruins under its new owner, Xander, a sandal-shod soul who has eschewed weeding, mulching, fertilizing, pruning. Minick ruefully picks some small berries. After his own struggles, he cannot condemn the man—but I’ll wager he never returns. Another calloused agricultural truth: it’s always a mistake to witness what’s become of your once-beloved fields.

—

Richard Gilbert is writing a memoir about his experiences operating a sheep farm in Appalachian Ohio for a decade. An excerpt, Kathy, appeared in Brevity 30, and another, which appeared in Chautauqua, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. His blog, Narrative, examines storytelling in creative nonfiction.