From a very young age, race defined my experience of the world. At the end of my second grade year, my elementary school hosted a party—a catch-all birthday celebration for the summer babies who would otherwise miss that opportunity during the school year. Another student and I were tied in a game, but there was only one prize. To decide the winner, my teacher knelt down and recited, “eeny, meeny, miny mo, catch the n*gger by the toe.” My mom was there and rushed the teacher like a tidal wave, demanding an explanation. The administration offered no apology, and she was left with only one decision—to remove me from the school. This wasn’t the first time I’d been called the n word, and I was only seven. My parents regarded the incident as typical, but continued to send me to predominately-white private institutions for the sake of a top-notch education. From their perspective, I was being afforded an opportunity in spite of race, whereas they were denied those same opportunities because of it. Like most children and adolescents, my need to belong overshadowed everything else. This clashed heavily with my parents’ vision. They weren’t paying thousands of dollars for me to make friends; they wanted me to get good grades.

From a very young age, race defined my experience of the world. At the end of my second grade year, my elementary school hosted a party—a catch-all birthday celebration for the summer babies who would otherwise miss that opportunity during the school year. Another student and I were tied in a game, but there was only one prize. To decide the winner, my teacher knelt down and recited, “eeny, meeny, miny mo, catch the n*gger by the toe.” My mom was there and rushed the teacher like a tidal wave, demanding an explanation. The administration offered no apology, and she was left with only one decision—to remove me from the school. This wasn’t the first time I’d been called the n word, and I was only seven. My parents regarded the incident as typical, but continued to send me to predominately-white private institutions for the sake of a top-notch education. From their perspective, I was being afforded an opportunity in spite of race, whereas they were denied those same opportunities because of it. Like most children and adolescents, my need to belong overshadowed everything else. This clashed heavily with my parents’ vision. They weren’t paying thousands of dollars for me to make friends; they wanted me to get good grades.

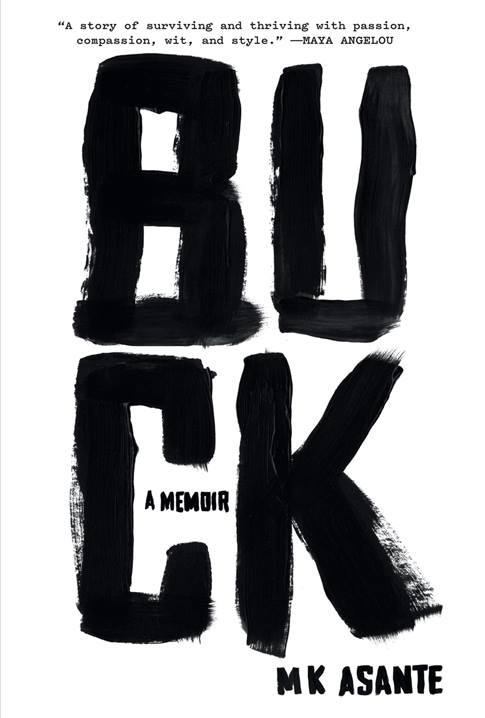

Buck: A Memoir (Spiegel & Grau, 2013)by M.K. Asante reminds me of the choice I had to make between belonging and realizing my parents’ hopes for my future. Early on in the book, Asante and his half-brother are confronted by their parents after their run-in with the law. They are given an all-too-familiar lecture about being black in America and growing up in oppressive poverty. The author includes a refrain to this family meeting, “If we made it from all of that—from projects and plantations—what’s your problem?” The answer is not an easy one. While there is a great deal of expectation, he is burdened by all that is crashing around him—an absent father, a depressed mother, and siblings who are lost in the system. And so he clings to what is familiar and constant: the streets and a band of high school dropouts he idolizes. My constants at that age were quite different from Asante, but I can identify with his discomfort in school settings that didn’t foster diversity and self-expression.

Asante grew up in a well-educated, pro-black household. He was armed with a comprehensive history of the African diaspora as well as the ever-present racism that surrounded him in Philadelphia. He is a guarded young man, but with real cause. His principal hates him, the police are billy club-wielding bullies, and his parents are emotionally unavailable. His narrative exposes the cracks in the veneer of his family life. Even as his revered father preaches a public message of black family unity, he is unable and unwilling to be present.

It’s easy to read this book and forget that you’re reading the memoir of a well-published, tenured professor. The stakes are high in this book, and you find yourself wondering what lasting intervention turns this young man’s life around. Along the way there are many lessons to be learned from Asante’s life, but the one that’s most compelling is perhaps the most universal: overcoming adversity. We like to tell ourselves that overcoming adversity is a straight-line forward motion, but it’s more like an amateur foxtrot. It’s a journey complicated by personal and family histories that requires you to sidestep all the familiar pitfalls and not look back. And like Asante’s life, it sometimes has a dizzying effect.

This book may depict a crude and unfamiliar environment for some of its readers, but it invites us to step inside the mind of a young man who is at an important crossroads. While on the surface it may be obvious which path to take, for many of us who identify with the author it may not always be clear how to approach it. One thing is certain, you cannot do it alone.

—

Sakena Jwan Patterson holds an MFA from Antioch University, Los Angeles. Her reviews have appeared in the San Francisco Review and In the Fray Magazine.