Sarabande Books 2011

My tolerance for excitement is low. So it was with trepidation that I agreed to chaperone my son’s sixth-grade class to an environmental learning center where the capstone of the week was the zip line. Students and chaperones alike braved the ropes course, high in the crisp autumn sky among birch and maple trees. The course ended in a triumphant zing across a high wire—to terra firma, to the waiting arms of chaperones, to the applause of supportive classmates. Coward that I am, I abstained. When you are a tentative soul, I explained to the less meek, life is a zip line. I happened to be reading Christian McEwen’s World Enough & Time and was struck by a quote: “Fall if you must fall; the one you will become will catch you.” Did I take that as encouragement to climb? I did not. I grew further convinced that just becoming is a highwire act. (Take that, adrenal gland.) That conviction, plus watching sixty eleven-year-olds interact, confirmed for me that our greatest challenges are more subtle and enduring than a manufactured obstacle course.

My tolerance for excitement is low. So it was with trepidation that I agreed to chaperone my son’s sixth-grade class to an environmental learning center where the capstone of the week was the zip line. Students and chaperones alike braved the ropes course, high in the crisp autumn sky among birch and maple trees. The course ended in a triumphant zing across a high wire—to terra firma, to the waiting arms of chaperones, to the applause of supportive classmates. Coward that I am, I abstained. When you are a tentative soul, I explained to the less meek, life is a zip line. I happened to be reading Christian McEwen’s World Enough & Time and was struck by a quote: “Fall if you must fall; the one you will become will catch you.” Did I take that as encouragement to climb? I did not. I grew further convinced that just becoming is a highwire act. (Take that, adrenal gland.) That conviction, plus watching sixty eleven-year-olds interact, confirmed for me that our greatest challenges are more subtle and enduring than a manufactured obstacle course.

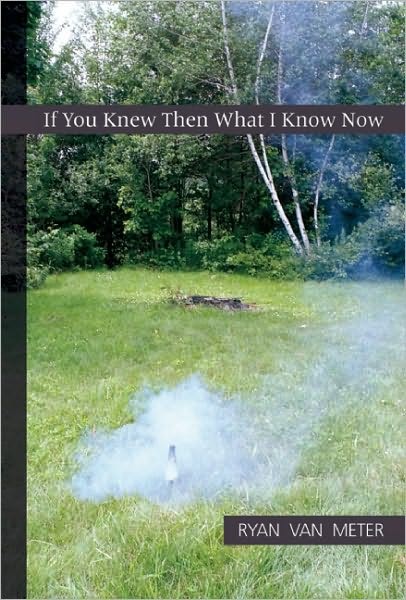

No book illustrates this more adeptly than Ryan Van Meter’s collection, If You Knew Then What I Know Now. Van Meter affirms what I saw in pre-pubescent faces all around me: it’s scary stuff discovering who you are and where you fit in the vast world. In fourteen linked essays, Van Meter does just that, walking back in time and toward self-discovery from his earliest memories to the present. There’s a distance between the world’s perception of “normal” and Van Meter’s; this collection is his intimate search to understand that gap. What he’s learning, with some trepidation, is how he came to discover he’s gay.

That he loves and wants to marry a boy at the age of five, for instance, feels intensely true: “What I know for certain right now is that I love him, and I need to tell him this fact before we return to our separate houses.” Van Meter’s mother overhears him proposing marriage, and his inner-reality clashes with the exterior world. Mother and son look at each other “for one last second without anything wrong between [them]” and she says: “You shouldn’t have said that. Boys don’t marry other boys.”

The essays progress (mostly) chronologically. Van Meter recounts setting the table for his grandmother while he’s wearing a dress, successfully avoiding kissing his girlfriend of more than a year—unsure, himself, why he’s content donning the former and dodging the latter. Van Meter’s observations are razor-sharp, sweet, and conveyed in selfless prose. His honest bewilderment wounds the reader while his graciousness rewards.

By the book’s end, that five-year-old boy has become a man aware enough to know what he’d like to say on a first date but won’t: “That we should split the bill. That you will have to lean in first to kiss me. That if you lean in first to kiss me, I will kiss you back.”

Van Meter navigated his own ropes course en route to adulthood and the person he’s become, it seems, has caught him. From the safety of my reading chair, I celebrate his landing.

—

Jennifer Bowen Hicks is the assistant nonfiction editor for Hunger Mountain. Her work appears or is forthcoming in The Iowa Review, The Rumpus, Brevity, Defunct Magazine and Connotation Press.