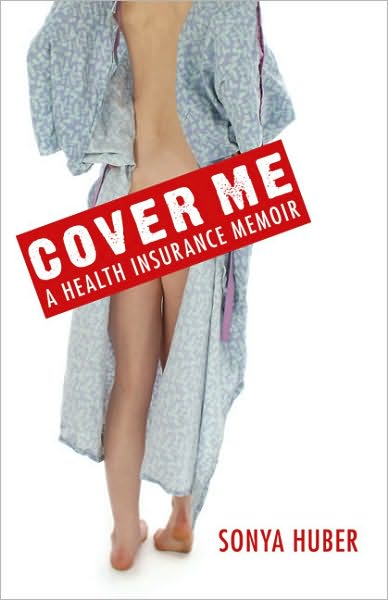

University of Nebraska Press, 2010

Just about as soon as I began Sonya Huber’s compelling book Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir I felt a friendly kinship. I’ve been the frazzled mama hoping a mega-shot of vitamin C will stave off impending illness, and I’ve also worked as a political organizer with noble intentions—a pile of picket signs in the backseat and sheaths of flyers jammed in my bag. Had timing or geography been different, I’m pretty certain Huber and I would have run into each other at conferences or playgrounds. I’m also certain we’d have plenty to say to each other about social change, writing, parenting, and life.

Just about as soon as I began Sonya Huber’s compelling book Cover Me: A Health Insurance Memoir I felt a friendly kinship. I’ve been the frazzled mama hoping a mega-shot of vitamin C will stave off impending illness, and I’ve also worked as a political organizer with noble intentions—a pile of picket signs in the backseat and sheaths of flyers jammed in my bag. Had timing or geography been different, I’m pretty certain Huber and I would have run into each other at conferences or playgrounds. I’m also certain we’d have plenty to say to each other about social change, writing, parenting, and life.

Though, here’s where we’d differ: I’d be her friend with the big house.

Unlike Huber, who writes, “By age thirty-three I had lived through eleven gaps in healthcare coverage,” I never worried about being without health insurance. I was a child of privilege turned adult of privilege. Money was largely taken for granted.

However, this changed when the market crashed. Money no longer provided the comfy cushion. Although health insurance remained an expensive given, the sense that a catastrophic illness could financially devastate us seemed much more real. Our insurance didn’t cover prescriptions or dental care. All costs beyond regular health insurance—be it additional childcare, ramps instead of stairs, or even long-term nursing—would significantly change our lifestyle.

In contrast, Sonya Huber had to fight for health care. Her tenacity, ingenuity, and steady wits awed me. Few people could finesse the system to extract the type of affordable care she obtained. The way she writes about her fighting-for-access drama causes readers to hang on every word.

For instance, after visiting a subpar dental clinic (because of lack of insurance), she tries to dismiss and even work around the mouth pain that lingers: “It was only sore because of the drilling. It was my sinuses. It was the cold. I had a caffeine headache… Over the next year, I resigned myself to chewing on the right side of my mouth. The upside was that the pain had morphed from savage and sharp to dull and predictable. At least I had teeth. All I had to do was ask for drinks without ice.”

Lack of insurance not only affects Huber’s health but her judgment. When she put off seeking medical help for a urinary tract infection, she ended up in the hospital with a 105-degree temperature. Her doctors lectured her: “This infection is in your kidneys. If it goes into your blood, there is nothing we can do.” Yet, she survived, but is left with a three-day out-of-network hospital bill.

Such are the consequences of being under insured, not to mention long-term health damage. Because Huber used Sudafed to treat a ten-year sinus problem, an allergist, years later, told her the drug may have damaged her heart.

Huber serves as a ready example that without health insurance, no amount of fighting assures decent health care. When financial worries are placed ahead of our health, we are all rendered insecure.

What I found so compelling about Huber’s story is her ability to make the personal resonate so much more loudly than the political ideas or theories, while capably insuring that her own story underscores her political stance on health care. I found myself wanting to send copies to every member of the House and Senate.

—

Sarah Werthan Buttenwieser is a freelance writer whose work appears in The Maternal is Political (Seal Press), Fourth Genre, Literary Mama, and the Southwest Review. She has a MFA from Warren Wilson College’s Program for Writers. Buttenwieser has her own blog, Standing in the Shadows.