For most of my adult life, I’ve struggled with identity issues, not knowing where or with whom I truly belong. To explain, I spent much of my childhood overseas, as the daughter of a diplomat, moving every few years and not establishing strong roots in one community. I felt as if I could fit in anywhere—or nowhere—a citizen of the world, not necessarily America. I lacked a place where I could call home, and this unsettled me, particularly after my divorce when I questioned when—or if—a new romance would make me feel at peace with myself. Then, a career change made me again question my identity: a journalist, teacher or writer? Where would I find meaning in my life, a place where I was perfectly content?

For most of my adult life, I’ve struggled with identity issues, not knowing where or with whom I truly belong. To explain, I spent much of my childhood overseas, as the daughter of a diplomat, moving every few years and not establishing strong roots in one community. I felt as if I could fit in anywhere—or nowhere—a citizen of the world, not necessarily America. I lacked a place where I could call home, and this unsettled me, particularly after my divorce when I questioned when—or if—a new romance would make me feel at peace with myself. Then, a career change made me again question my identity: a journalist, teacher or writer? Where would I find meaning in my life, a place where I was perfectly content?

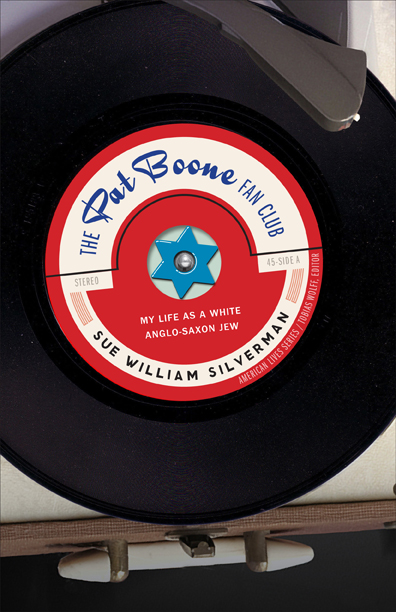

In her latest memoir, The Pat Boone Fan Club: My Life as a White Anglo-Saxon Jew (University of Nebraska Press, 2014,) Sue Silverman also explores where she fits in as she wades through the experiences of being a reporter, wife, and victim of sexual abuse. She longs for the love of a caring, decent father, not the one who had sexually abused her as a child. She searches for a person to protect her, as a father would, and finds the pop singer Pat Boone to be someone who might replace the affection she lacked. In Pat Boone, she finds hope, a way to stay alive despite the horrendous acts she endured as a child. “I conjured him into the man I needed him to be: a safe father,” Silverman writes. “By my believing in that constant image, he did save me, without my being adopted, without my even asking.”

Pat Boone comforts her with the hope of a safe world where no one can harm her. But she still struggles with the fact she is Jewish in places populated by gentiles. In middle school, Silverman wants to shed her identity as a Jew to fit in with the predominately Christian community of Glen Rock, New Jersey, and win the love of Christopher, a Christian. But, at home, so much prevents her from connecting with someone outside her faith: the mezuzah on the doorpost, a gold-plated sphere intended to protect Jews from future pogroms; her grandmother, who lives with Silverman’s family, invading the house with her black babushkas, Yiddish tongue, and scent of boiled cabbage; and the Star of David gold chain around her neck, which she takes off at school and hides it in her saddle shoes. She questions if Christopher would love her if she looked Christian. “Christopher, would you be bad with me, kiss me—do more with me—if I didn’t look Jewish, if I resembled Lynn or Sandra Dee?” she asks.

Silverman marries, but the relationship falters as her scholarly husband is more occupied with his research on a book than her. She writes, “Why do I even remain married? Buried in his philosophical books, deconstructing words and sentences for a living, my husband never notices the absence of a real me.” She thinks of herself as a hollow woman, who regularly changes roles like fads. Yet, finally, in the end, her idol Pat Boone comforts her. He’ll be there to smooth over all the wrinkles and creases in her life. In an imagined conversation with him, Silverman asks him what he would do to keep her alive. In her imagination, she hears, “For you, he says, I would iron the night.”

—

Jennifer Nelson recently graduated with an MFA in creative nonfiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She now teaches high school French after spending years writing for newspapers and magazines. Her work has appeared in Connotation Press, Writing Through Your Divorce, and Brevity.