We buy the sheep on impulse, a pair of them, at auction. They are tufted round with autumn fluff, white-grey fleece with pink skin by their ears and nostrils, wafting the oily tang of lanolin. After two seasons of raising skinny, worm-ridden goats, shelling out for the overpriced sheep feels indulgent, like driving a new truck right off the lot.

The light is already going dim when we careen into the driveway with the plywood box full of sheep strapped to the truck bed, and they need stalls built. Just until tomorrow, we say, as Tim backs the tailgate up to the front paddock. I pull apart the box with a pry bar and push the mewling sheep down into the slippery grass as the sun falls behind the mountain. The paddock is ungrazed, dotted with dandelions and dog shit—plenty big enough for one night.

*

In the upstate nights I like to read magazines in bed while eating bowls of hot baked squash with cold salted butter, to fall asleep with glossy pages tipping down to my chin, my mouth gummy with salt and fat, the flaky brass lamp’s bulb glaring at me, my shoulders so spent from mucking stalls that stretching an arm up to spin the knob is a bodily extravagance I can’t easily afford. I like this exhaustion, this ground-down-ness.

Tim is different. Restless. Discontent. He wakes me roughly with a strong hand on my ribcage, rattling me, same as he does to the animals.

Get up. This is not a question, not a request. Get up.

I don’t have to ask why. It’s always the same trip, sixty miles north-northwest, out of New York State, onto Oneida Nation land. His already-bad eyes are burnt from twenty years of welding, he gets sleepy when he drives at night. He needs me.

We shouldn’t leave the sheep untended right now. They don’t know where home is. We both know this. But Tim can’t say no to the call of Texas Hold ‘Em, and I can’t say no to Tim, not tonight anyway, so we pile back into the truck, me bleary, him tense, and I drive, the hungry growl of the diesel engine just loud enough to keep us from talking.

When we arrive, he speed walks away from me, into the poker room. I buy myself a pack of untaxed Marlboros and order a free Diet Coke. It’s difficult to know how long we’ll be.

I sit in a deep pocketed windowsill, the baseboard heaters burning my calves and the glass chilling my back, relishing the balance of these discomforts.

*

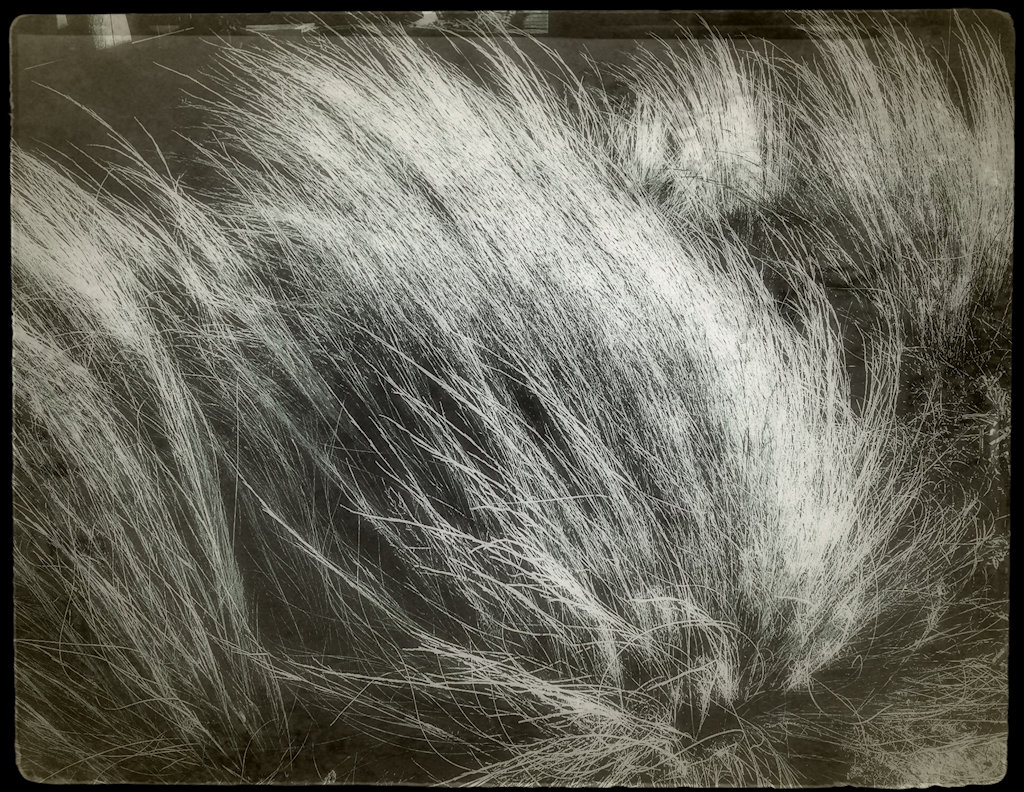

Perhaps the sheep are now fumbling in the shiny blackness of upstate midnight, bumping into the unfamiliar fence beneath the swollen moon, becoming nervous as the smell of coyotes grows thicker.

In the overlit casino bathroom I try to scrub the cigarette stink from my fingers, but when I raise them to my nose, the echo of the smell remains under the fake-fresh of antibacterial soap.

Perhaps the coyotes are now yipping, like they do under every full moon. Perhaps they are circling, hocks and knees crouched, gathering spring, circling, circling. Perhaps the sheep are crying the same plaintive bleats they cried when we crammed them in the box and strapped it to the truck and turned the engine over, the Cummins rumble loud as an approaching train.

When we make it home in the morning, well past ten, the sheep are gone. The fence: unbroken.

We are haphazard farmers, and our animals are used to curling around their bellies till we make it to the barn, but now there is a new stillness. We walk the property, searching, hoping, for most of the day, even after the farmer up the hill—a real farmer, him, with a hundred head of dairy cattle, a thresher, and a missing tooth—tells us he heard coyotes real loud last night, like they’d kilt somethin’ or somethin’. Even then, I hope our sheep will come trotting down County Highway 19 like teenagers sneaking home past dawn.

In

springtime, we find their skeletons on the far side of Curley Road, past our

property line. The meat is stripped and the bones weathered, but scraps of

fleece remain, making us certain that we failed exceptionally at shepherding

these poor sheep, certain that this pile of bones is what our care has made.

__

Margo Steines is a native New Yorker and journeyman ironworker. She lives and writes in Tucson, Arizona, where she is an MFA candidate in nonfiction at the University of Arizona. Her work has been published in Essay Daily, december, Tits and Sass, and The New York Times (Modern Love), and is forthcoming in Off Assignment. Find her here on Instagram.

5 comments

Michael McKniff says:

Jan 28, 2020

Haunting

Nels Highberg says:

Feb 1, 2020

Absolutely blew me away, and that we before that last paragraph because I never thought you would actually “find” the sheep. And the use of “we” and “our” even at the end is so telling about how you two are still tied together at the end. Fantastic.

VICKI WHICKER says:

Mar 22, 2020

Fantastic writing. More of this please.

Linda Stone says:

Aug 9, 2020

so honest and beautifully written

kia says:

Feb 8, 2023

as an upstate new yorker i know the cry of those coyotes well. they’re haunting.