In his maximum-security prison, where I visit him for the first time, Kevin suggests that with our eight remaining quarters, perhaps we should try the photo booth. This is something he wrote about in his letter: how a photo would mean so much.

In his maximum-security prison, where I visit him for the first time, Kevin suggests that with our eight remaining quarters, perhaps we should try the photo booth. This is something he wrote about in his letter: how a photo would mean so much.

I can’t keep the film copy, he wrote, but you could scan it and mail it to me and I’ll tape it to my wall.

The idea of the photo booth was, of course, alarming: the idea of sitting on his lap. The idea of that tiny, curtained space. As a child, I’d sat often in photo booths—inside movie theatres and skating rinks, my friends and I widening our eyes, pulling apart our cheeks to show tongues blue or green from Pixie Sticks. It was, in short, a thing of pleasure.

But to squeeze now inside one with Kevin, I was afraid, would force that uneasy reminder: that while he is my friend, he is also a murderer. That he stabbed a nineteen-year-old girl to death. And it doesn’t matter that he then phoned the police; it doesn’t matter what three separate psychiatrists deemed it. It cannot matter the guilt he feels, the ownership he took, the sentence he’s now serving.

The apologetic speech he gave at his hearing.

The apologetic letter he wrote to her family.

I wish I could take it back, he wrote. I lost control somehow, but I wish to God it was my life I took.

Three years and a thousand miles away, I can sit on my couch and forget what first happened. I can trust the authorities—that something did, in fact, happen. I can imagine my friend’s brain a wire: a red and sparking ember fissuring through the drywall of his mind.

I can get over the strangeness of what it is to be Visitor #3 on his prison visitation list, just after his mother and father, and because he’s allowed ten, there are seven more behind us—Tiffany and Eric and Sam, Andrew, Keith, Allison, and Brandon—names Kevin put down “just in case,” because gaining clearance to be on his visitors list can take months, so I should do it now, he wrote, just in case they ever come. And what I know that Kevin doesn’t is that they won’t ever visit—“It’s a shame he didn’t get the chair,” one said, “for the things he did to that young woman,”—but for four years, Kevin was our friend, and what does friendship mean if, when he needs us most, we’re gone?

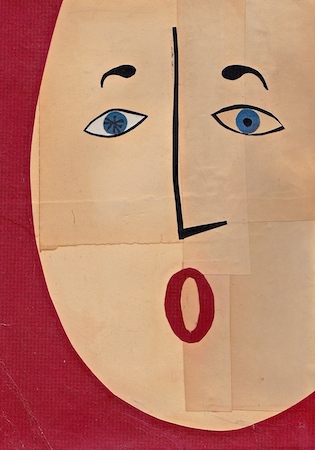

So I can be here, in this prison. But in this photo booth, there’s no pretending. I am sitting on the lap of a murderer; it would be obvious even to me. Never mind his face, his skin, so young and white it might as well be paper. Never mind his smooth, brown hair, cut to frame his skull like a mushroom cap—the same cut my brothers got, my father asking them to please sit still atop the backyard picnic table. Never mind that Kevin, like me, is twenty-five, just three months my junior, or that the towns where we were raised were just seventeen miles from one another. Never mind his hands, which move the way an animatronic moves—controlled, abrupt motions, because it is very clear he is nervous.

In the photo booth, in this prison, we would be so close that he could hurt me. And I want to think that it would never happen, but it happened once, so who can say?

“We only get one photo,” Kevin says, and when I finally bring myself to look at the machine, my mind turning over the words I’ll use to carefully turn down his offer, I realize there is no booth or curtain; there is no small, no intimate space. That it is just a boxy piece of equipment. The background, even, is empty: a sterile, white cinderblock wall.

“Oh,” I say, “sure,” and I stand beside him as he scrolls through photos that can serve as our digital backdrop. There’s the Eiffel Tower, or underwater. We can be on a roller coaster or in a rain forest or deep in space.

We can be on Everest.

Finally, Kevin selects No background, and we see our image on the small glass screen.

“You’re going to have to make me laugh,” he says. He says it quietly, self-consciously, and I try to think of a joke quick but can’t. The screen counts down until the flash—3, 2, 1—and I think of a joke a boy told me once as we were driving home from a bowling alley.

“What kind of dog has no ears?” I begin to say to Kevin, ready for the emphasized, “Corn dog!” but I only get to “has” before the flash lights up and breaks.

In the photo that prints at the front desk, my mouth will be open, and my eyes shut.

__

Amy Butcher is a writer and author of the recently released Visiting Hours, of which this essay is an excerpt. Her recent essays have appeared in The New York Times, Guernica, Gulf Coast, The Indiana Review, The Iowa Review, and Fourth Genre, among others, and she was recently awarded the 2014 Iowa Review Award by guest judge David Shields. She earned her MFA from the University of Iowa and serves as an Assistant Professor of English at Ohio Wesleyan University.

3 comments

Lauren Marie says:

Dec 27, 2015

This is so hauntingly beautiful. I really enjoyed reading.

ian says:

Jan 14, 2016

great stuff. I wonder how long this took you to write.

AC says:

Feb 24, 2016

This is so well-written. It captures so much – Kevin’s backstory, the fear of taking a picture with him…I’m in awe.