We begin our descent somewhere over Normandy when I read in Let’s Go! France that the Eiffel Tower is this beacon for suicide. Host to twelve successful attempts every year. Katja tells me the jumpers tend not to be locals. She says no Parisian would be caught dead anywhere near the Eiffel Tower, and by the end of the first day I know that she’s right.

We begin our descent somewhere over Normandy when I read in Let’s Go! France that the Eiffel Tower is this beacon for suicide. Host to twelve successful attempts every year. Katja tells me the jumpers tend not to be locals. She says no Parisian would be caught dead anywhere near the Eiffel Tower, and by the end of the first day I know that she’s right.

Still, I want to see the tower right away. Just as soon as we get off the plane. I want to confirm its existence and fortify mine. Tourism is the only religion I’ve got. My faith rests comfortably in shiny hotels with walk-in thermostatic showers that fire at the body from six different angles. Katja and I ride the tower elevator a thousand feet into the sky with a group of very elderly Americans. They advise us to be on the alert for nausea and pickpockets, and to drink plenty of fluids.

Parisians. They murmur like little doves. They cluck and they coo. No matter how long we end up living here, I know I’ll never learn to speak that way. And I understand, too, from the moment we arrive, that Parisians are too discrete to hurl themselves from international landmarks.

We walk along Rue de Grenelle, it’s this teeming neighborhood street where shopkeepers shake hands with customers. Everybody knows everybody. Everybody knows French. I can’t imagine learning French by living here any more than by living in the sea I could learn not to drown.

The more we walk, the more difficult it becomes to avoid mention of the city’s high concentration of lingerie boutiques. During one fifteen minute stretch we pass more lingerie shops than pharmacies. For every chicken roasting on a spit, there’s sexy lingerie smoldering in the boutique window next door. I try to be a man about it. Try not to stare. But every time a woman emerges from a lingerie shop, I can’t resist studying her face for signs of lifelong erotic contentment.

Katja approaches the window of a designer lingerie boutique, so high-end there’s hardly any merchandise at all. Every item has the delicate vascularity of a burning leaf. Her eyes settle on a pair of black stockings.

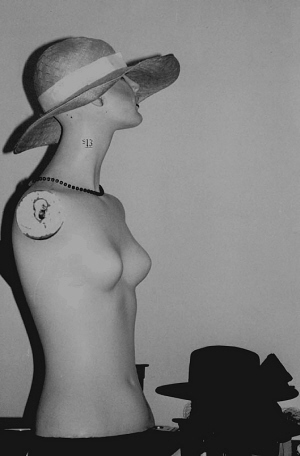

Where I grew up, they sold women’s underwear by the six-pack. They lashed ill-fitting underpants to mannequins with screw-on body parts and staked them over sale-bins like scarecrows. I feel lacking in some essential training that French men are required to undergo before they’re allowed access to public life. Some sort of erotic inurement. When I ask Katja if French men are circumcised, her glance betrays this dwindling reserve of pity.

She says the USA is the only nation in the world that practices genital mutilation on men, and segues into one of her pet theses: that I am, without knowing it, the victim of my own manhood. That somehow, having been circumcised, having been exposed to too much pornography too early in life, having lost teeth in fights, having a tendency to drive cars offensively, that somehow all this makes me a victim. I don’t feel like a victim.

—

John Bresland works in radio, video, and print. His essays have aired on public radio, and his video essays can now be seen at Ninth Letter and Blackbird online. His print essays can be read in North American Review, Hotel Amerika, Minnesota Monthly and elsewhere. He is an artist-in-residence at Northwestern University, where he teaches creative writing and new media.

**[Hear John Bresland’s audio version and

why he wanted this essay to be experienced as audio:

John Bresland on the Brevity Blog ]

photo by Kristin Fouquet