“That’s the sound,” Lucie says. “Like this.” She makes her hand thin and rigid in the white-blue computer glow. She stares at the hand, vibrates it in a stiff palsy before her face.

“That’s the sound,” Lucie says. “Like this.” She makes her hand thin and rigid in the white-blue computer glow. She stares at the hand, vibrates it in a stiff palsy before her face.

Lucie’s on the far side of the couch, half-reclined on the oversized throw pillow an ex-girlfriend made for me long ago. The cat, curled dormant between us, perks up her ears at the tone in her voice, one that seems surprised, charged, almost relieved.

A stunned man stumbles through the concrete rubble of a terrorist strike. The computer screen swells with gray plumes of billowing dust. The audio has dropped out. There is nowhere to orient, the landmarks gone or obscured. Shadows of color wash across the room, Lucie’s hand, the waves of light, now proxies for the almost-absent sound of the movie, the almost silence.

“Really?” I say. “Like that?”

Since the bombing, watching them explode on TV has never been a problem for us. Blown by the blast wind, the hero invariably stands up to face another day, to save it, with perfect hearing. The absurdity of it always makes us laugh. But neither of us are laughing now.

Normally I’d lean toward the coffee table, hit the space bar on the laptop, pause the movie so we aren’t talking over it, but I need it to keep going, to hear the sound, her sound, a little longer. It’s terrible—thin and rigid and unrelenting, an interior metallic intrusion that colors the scene unfolding before us.

“Really really,” she says casually. But then she looks at me down the length of the couch with curiosity, perhaps surprised at my surprise. Maybe I’ve been the one surprised all along.

“That’s what it sounds like for you every day?” I ask. I know the answer by now, but I’m stumbling for purchase on this new reality, this divergence of our shared one.

I touch the scar behind my right ear. I can’t see the one behind Lucie’s from here, not even as I lean forward to pause the movie now. The cat, disturbed, leaps from the couch, becomes a dark shadow in the background, darker than the room. Blood drips from the man’s ears, dark red rivers down his neck. That didn’t happen, not that way, not to us, not to anyone else harmed in the attack. But the movie is reaching, if a bit too far, for a reality. And it isn’t a funny one.

The symmetry of it all—the same ear lobe cut away by the same surgeon, cut to build a new ear drum the very same way—had cast a spell of shared experience across me. I thought it was the soft rumble, the whoosh that she heard, like we both did during that eardrumless month pre-surgery so many years ago. Not this terrible sound that hurts to hear, that I’ve heard for the first time so many years later.

I touch the lumpy scar behind my ear lobe where it meets my skull and wonder now if Lucie’s is lumpy too. I’m unsure. I stare down the couch at my wife and try to see her anew. What else don’t I know because I think I do, I wonder.

“So?” she says. “Are you going to restart it or what?”

I lean toward the bloody-eared man, tap the space bar, resume the movie and its sound, which soon becomes the sound of the world once again.

__

David Naimon is a writer and host of the literary radio broadcast and podcast, Between the Covers, in Portland, Oregon. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in AGNI, Tin House, Fourth Genre, Boulevard, and Zyzzyva, among others, and has been cited as a 2016 Pushcart Prize Special Mention, and a 2015 notable in The Best American Essays and The Best American Travel Writing.

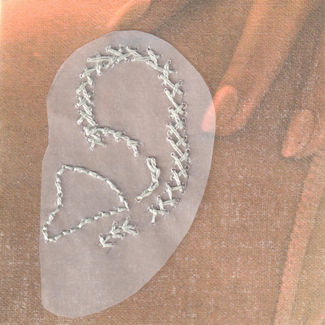

Artwork by Allison Dalton