Who

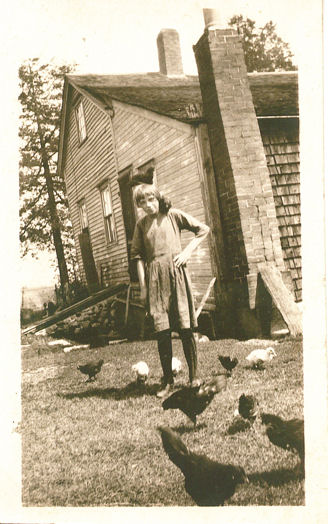

Oh my god, who is she? I want her for my own. I want her affinity with all those chickens, her lopsided leaning, her house all atilt. I want that tipping chimney and the angle of her neck as she lets one hen push its way into her heart, another pose as a hat. I want that practical dress and the long black stockings, even the sensible shoes. The light that fattens itself on late-afternoon windows, and the shadows that lengthen the yard. The chickens that peck at their shadows, whittling away at their lives. Look at the way light catches each shingle, each brick, each clapboard lining the side of the house. Look at it fasten itself to the folds of her skirt.

This was a moment—the day of the chickens. But all days were chickens, scattering feed, and gathering eggs. Off lens: the henhouse with its strange, musty odors. Off lens: the rustle of worry at the doorway, the nattering fuss as her fingers sift through straw. Chore after chore. The lifetime that added more, and then more.

I want this moment, but not what it stands for. Want one minute of overlapping shadow, one slapdash second of light. Quick, while she has a perch on pleasure. Quick, before her tiny breasts grow bigger, before she lifts up her hand to lift down that feathery weight.

Where

Head-high in corn. Surely that girl is me, so familiar the scene. I can hear it grow. Husks brush against the leaves, a bit like the sound of women’s silk stockings, saved up for fancy occasions; the leaves click and mutter in the breeze and tassels wave their fingers. It could be me under that canopy, losing myself in those endless rows, scaring myself with the thought that I’ll never find my way out. That I’ll turn and turn under all that whispering, get lost in the shadows that snap at my feet.

The back of the photo says “Grandpa Lammert and Linda in Charles Cornfield on Aug 20—1946” and the writing looks suspiciously like my own grandmother’s, but it could belong to someone else. There are no Lammerts in our family, and whoever Linda is, I’ve never heard of her. Still, there’s an intimacy, even in such a short summation, because someone somewhere thinks that someone else knows Charles. Might even imagine the contours of this cornfield, or place it with pinpoint precision on a map.

It’s 1946, the year after the war, and everyone is filled with a feeling that corn will grow taller and taller, now that the boys have come home. Surely Linda is five, like me, about to go off to kindergarten, like me. She even has my overalls. But she has a grandfather to stand there behind her, his straw hat measuring the harvest, while mine are not even a part of my memory—more legacy, or lore. I love the way he hitches his britches high on his waist and the way his shirt becomes part of the blazing sky. She’ll never get lost.

Though I’ve lost her. That is, time has erased the moment she shared with a man who shared in her future. Expunged anyone who could help me find this unlikely twin, wherever life has taken her. Linda, I’m here, I call through the cornfields. Here, she echoes. Over here, I call. But the leaves lift emptily in air, and the sun keeps on humming over our far-flung heads. Somewhere my mother pulls my hair back tightly into my braids and sends me out the door. I could get lost, but I won’t.

Judith Kitchen is the author of two collections of essays, a novel, and a book of criticism. In addition, she has edited three collections of short nonfiction pieces (In Short, In Brief, and Short Takes) for W. W. Norton. She lives in Port Townsend, WA, where she serves on the faculty of the Rainier Writing Workshop Low-Residency MFA at Pacific Lutheran University.

photos provided by the author