“All grants of land made by the Mexican government…shall be respected as valid…” —ARTICLE X, Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed by representatives of Mexican and U.S. governments in February 1848; stricken from treaty ratified by US Congress in May 1848

“Our people were kings,” your father would whisper after handing over the day’s corn and chile verde to El Lagartijo, a man with one polished star to hold up his pants and another to cover his heart. A man whose boots were never dusty, even when he sat at a table in the fields, a scale beside him, the harvest stacked in burlap behind him, a ledger opened before him, the curandera holding an umbrella over him. A man with thick hands and skin so clear you could almost see his blood run. It made him seem more real, more alive somehow, than you, your father or any of the Mexicans on the new border.

Now you must ask permission to pull chile verde or tomatoes from the vines. So many for them. Sometimes there is enough for you.

El Lagartijo’s doctor opens your father’s mouth, tapping his teeth with a silver spike, the way your father once inspected horses. “This one can work,” he says.

One day the curandera is gone. Before Lagartijo and his doctor, the people paid her to heal. She was the first to hold you as the afterbirth and too much blood gushed from between your mother’s legs. Your father gave her the calf he’d smoked in a desert pit, eggs to cleanse your blood and spirit, rosemary to sweep away el susto. Susto. A fright so great it sends the soul into hiding. Now the calves belong to the company—a mine, a railroad, a ranch. The eggs and even the herbs belong to the town, which is just another name for mine or railroad or ranch.

You imagine the curandera becomes wind.

El Lagartijo will take you one night. His boys will take your daughters. You are property here. This one can work.

They make your father sign a parchment littered with a language he can’t read, and the next day they come to collect. You learn a new phrase that day. Water rights. You never knew a man could own what so clearly belongs to the earth.

You will sign with an X, the only letter you write, the same in either language, on either side.

Now there are sides. Us. Them. (And you don’t know which you are.) Up. Down. Here. There. They will come up here from down there. They won’t stop. No matter how many fences, how many Rangers tracking them through crosshairs, how hot the sun that spirits of dead mothers blow across the sky. No matter how strong la migra, how many signs on this side reading “No dogs or Mexicans allowed.”

They will come.

You bury your father on the plot set aside for “you people,” mark his grave with an agate you place face-down and lift only in those silent moments when you whisper to him, squatting on what must be his feet. Tracing your dark finger along concentric bands of color, you imagine a heart cracked open must look the same way.

Our people were kings.

You will forget that your people built Paquimé and Tenochtitlán. You will never climb the steps leading to the moon at Teotihuacán. Your children will learn half of two languages and that will never equal one. This new country will hand them uniforms—soldier, miner, waitress, mechanic. Their names stitched in red over their hearts, your children will wander across these lands, thirsting beneath the Fifth Sun.

Michelle Otero is the author of Malinche’s Daughter (Momotombo Press, 2006), an essay collection based on her work with women survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault in Oaxaca, Mexico. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Puerto del Sol, Artful Dodge, Border Senses, and other journals in the U.S. and Mexico. A graduate of Harvard University and Vermont College, she currently resides in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

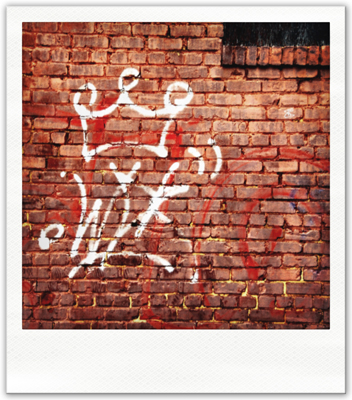

photo by Leslie Miller