One evening in the swamp-city where I used to live, at the mouth of a river opening into a salt ocean tide, in an apartment building known for jumpers, the woman upstairs tells me about her pain.

One evening in the swamp-city where I used to live, at the mouth of a river opening into a salt ocean tide, in an apartment building known for jumpers, the woman upstairs tells me about her pain.

We ride the elevator, laundry in our arms. The lift jutters as it passes each floor.

Her back is crumbling, my neighbor says. Guts in a mess of knots. The doctor won’t up her dose. Her little dog has run away. Everything hurts.

She twists at her hair. She is in pain, she says. Pain.

I say nothing to this. I believe her, but not really. This building is full of addicts. This town has a heroin problem. She is not the only one in the apartment with phantom itches under her skin.

I exit the elevator on my floor. I tell her I hope she gets well.

All night I can hear her moving furniture in circles round the rooms, the clockwise rasping noise like low-bottomed boats arriving on stony shores. When she hits a bump the floor shakes and sends little showers of dust and plaster onto my bed. She shuffles, dragging her feet.

Pain, she said. Everything hurts.

I fall asleep to that hushing sound, eventually not knowing if it is the river, five blocks away, or my neighbor’s endless tread.

*

Many years ago, the horror movie Blue Velvet was filmed in this building. With a cult following and indie accolades, it is an often-brutal and sexually violent film, with scenes of sadomasochism and domination against a backdrop of psychological disturbance. I avoided watching it so that I could live in my apartment without more than the normal amount of worries that accompany living, as a woman, alone. Still, I was always aware I slept in a room where a woman had been filmed pretending to be tortured.

*

All winter I listen to my neighbor carve tracks in her floors. While she paces I sit in my window and look across the street where an antebellum mansion’s white columns glow in the lamplight. The stone back buildings, where—the tour guide is reluctant to confirm—people were kept in chains, are not visible from the street. If there has been rain, dark shapes rustle across the sidewalks—not leaves but Palmetto bugs, fast and slick. The ground is always moving here: the river: the ocean: the swamp flats. Nothing remains in place for long.

Every night I watch and wait for the man I am seeing to arrive, slouching through my door, bringing that river-scent, bracken and mold and shark bait, into the room. I am in the depth of love for him. I am terrified he is going to leave me.

I keep the door unlocked so he can enter unannounced—I like imagining he lives here too. And also to pretend—to force myself to believe—that I am not nervous living alone. That I do not know what happens to women who leave the door open.

We eat, and talk. I tell him about my upstairs neighbor’s progress. And when we are ready, we will enter the bedroom together, in which he will loop a length of rope around my wrists and ankles and tie me to the bed. And once we’ve lit a candle and locked the door, he will use a belt on me until I have decided I hurt enough.

Most often he asks to stop before I do. Though what we do excites him, he is very afraid of damaging me. I know this is not the way that will happen.

*

In the spring, I pass my neighbor in the foyer. Her little dog has not returned, she reports. Her teeth are loose. There is mold in her baseboards—from the river damp. Everything rotting from the inside out.

I tell her I’m sorry. I don’t think she believes me, really.

I sometimes wonder if she can hear the sounds from my apartment below, if I keep her up at night. It makes me nervous to think how much she may understand me.

Pain, she says. Everything hurts. I believe her. I always have.

I wonder what would happen if you peeled the building walls away and saw us, carving tracks in wood and flesh, the thinnest floor between us. All those things real and created, right there under our skin. Now bared, opened, the salt river bearing it away.

__

Bridget Apfeld is a writer and editor living in Austin, Texas. Her work can be found in a variety of journals, most recently including Midwestern Gothic, Dappled Things, The Fem, Able Muse, So to Speak, and more. She is currently revising her latest novel.

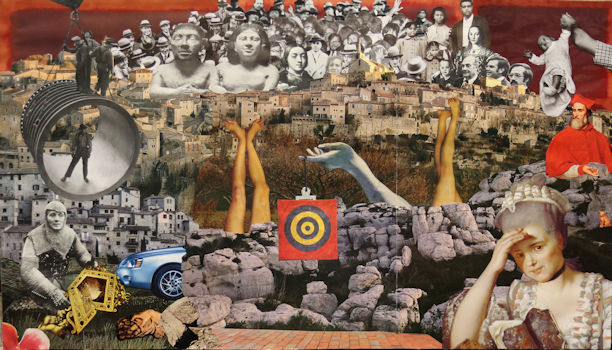

Artwork by John Gallaher

2 comments

Nina Gaby says:

May 18, 2018

I just wanted to acknowledge that I read this. So beautiful. With something for everybody, but they would likely not want to admit it.

Aurora Shimshak says:

Jul 19, 2018

Stunningly beautiful. I was thinking about it yesterday as I drove to get groceries and didn’t even notice that it had started to pour. Today I had to read it again. The line that gets me: “It makes me nervous to think how much she may understand me.” And that closing image, thank you for that.