In my high school, where God was king and country and girls were not, everything teetered on the tightrope of treason. We knelt like mendicants while nuns used their wooden rules to measure the distance between the immaculate floor and the hems of our box-pleated mini-skirts. Because length and sexual proclivity were intertwined in the nuns’ imagination, everything was on the line. A half-inch could determine whether we were sent home in disgrace or permitted to remain in school. We sluts would mumble a quick prayer to the Virgin, who befriended everyone, including sluts like us and Mary Magdalene.

In my high school, where God was king and country and girls were not, everything teetered on the tightrope of treason. We knelt like mendicants while nuns used their wooden rules to measure the distance between the immaculate floor and the hems of our box-pleated mini-skirts. Because length and sexual proclivity were intertwined in the nuns’ imagination, everything was on the line. A half-inch could determine whether we were sent home in disgrace or permitted to remain in school. We sluts would mumble a quick prayer to the Virgin, who befriended everyone, including sluts like us and Mary Magdalene.

But when a slut called Lillian shocked us all one lunch time by lobbing a defiant “No!” at Sister Mary Jude, hegemony collapsed in on itself like a dentureless mouth. I don’t remember what exactly Lillian was refusing to do; I don’t remember if the heretic was expelled or suspended. But I do know whatever they did to that brazen hussy wasn’t punishment enough.

Later, when the Jesuit-priest-turned-New-Age-therapist descended on London’s Clapham Park to hear our convent-girl confessions, he was armed with the belief that the devil was in the details. The inquisitive cleric demanded to know everything we knew about heavy petting. “Do you let your boyfriend touch your breasts?” he’d whistle through his dentures. “Describe precisely how he does it. Does he pull on your nipples? Tell me, child, do you let him run his fingers up between your legs?” His gynecological inquisition forced us to ponder our positions in the world of men.

Still later, co-educated and cocky at King’s College, and wearing skirts up to my armpits, I read and re-read Paradise Lost, reciting the fallen angel’s blasphemous, Marlowe-indebted blank verse. And now, when I think of libertine Lillian defiant by the fold-out tables (where “lunch ladies” like my mother served us slabs of papillaed ox tongue, sweaty liver and onions, flaccid rashers of bacon, storm-grey mashed potatoes, and spotted dick—yes, spotted dick), I remember a girl who never looked down. Her black Irish hair formed a scruffy halo around her face, her don’t-give-a-crap Mad-Men glasses winked at the damned.

Like the Bible, this moment was all about begetting. The Lillian-Said-No Incident—a Satanic ritual that lasted less than a minute—begat an inaudible, estrogenic, unstoppable ascension. Orifices opened; boulders were pushed to one side as the lissome female body was resurrected. It belly danced while gazing upon its own navel. It rose like the Holy Ghost’s deviant sister, tonguing the air.

In that moment—a moment as wing-beaten as orgasm—I found myself inside the holy corporeal cave of the soul repeating one simple word: “Alleluia…Alleluia…Alleluia…”

__

Lucinda Roy is an Alumni Distinguished Professor in Creative Writing at Virginia Tech where she teaches poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction in the MFA program. Her novel Lady Moses (HarperCollins) was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection, and her poetry collection The Humming Birds won the Eighth Mountain Poetry Prize. Her memoir-critique No Right to Remain Silent: What We’ve Learned from the Tragedy at Virginia Tech was published by Random House. Her poetry, fiction, and commentaries have appeared in numerous publications, including North American Review, American Poetry Review, Callaloo, Prairie Schooner, River Styx, Poet Lore, Crab Orchard Review, USA Today, The Guardian, The New York Times, The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Hill. Her new collection of poems, Fabric, is forthcoming in February 2017 from Aquarius Press.

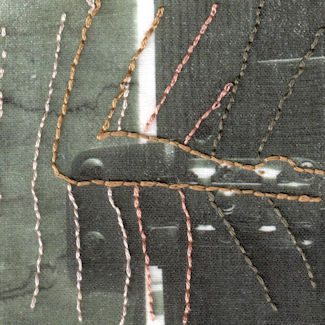

Artwork by Allison Dalton

3 comments

DHnLA says:

Jan 22, 2017

I enjoyed the rebellious, this-is-who-I-am, deal-with-it tone and message in this piece.

Marie says:

Jan 31, 2017

Thank you, from a life-long recovering Catholic, for expressing your epiphany of the power of the sacred Feminine–sexuality intact!

Susan/s says:

Apr 21, 2017

This is an epiphany that takes far too long for many women, even in the 21st century. Thanks for expressing it with such candid and humorous style.