Everything belonged to Russell now. My mother was his wife, I was his son, we lived in his house—an isolated farm we didn’t need and couldn’t afford. Russell had started cutting trees off the property and selling the timber to make the mortgage payments. He was sharpening the teeth of a chainsaw on the front porch when I came outside to ask him to kill my cat.

Everything belonged to Russell now. My mother was his wife, I was his son, we lived in his house—an isolated farm we didn’t need and couldn’t afford. Russell had started cutting trees off the property and selling the timber to make the mortgage payments. He was sharpening the teeth of a chainsaw on the front porch when I came outside to ask him to kill my cat.

I stood watching him run the file between the links while he explained why a dull chain can be dangerous.

“The orange cat is dying,” I said. “It won’t leave the bathroom and it’s starting to stink.”

I put my hands in my pockets. It was overcast and not very warm.

“I’d take that cat in the woods and shoot it if your mother wouldn’t throw a fit,” he said. He made threats before to shoot the pets if they pissed on the rug or were caught on the kitchen table. He made other threats to cut the power to the house or burn all my clothes if I sounded like I wasn’t happy here.

“Mom’s not going to be home for a while,” I said. “I wouldn’t say anything about it.”

He stopped and tapped the filings off the chain. His hands were grease-covered and scarred. He spit on the concrete. I was made to watch many things happen and that cat dying was the most specific.

“I’ll go get the 12 gauge if you get the cat,” he said.

Russell walked ahead of me, holding the gun at his waist with the hinge open and the barrel pointing toward the ground. I petted the cat as we walked past the barn. It was thin with scabs on the back of its neck. It purred some.

He stopped at the top of an embankment near the guardrail. I handed the cat to Russell and turned around to face the road. I listened to his boots crunch on the leaves going down the hill and then the gun’s hinge clicking.

“There’s a time to live and a time to die, cat,” he said.

I jerked when the gun went off.

“His troubles are over,” Russell said, walking past me.

Back in my bedroom, it was dim and quiet lying on my bed until the chainsaw started outside. From the window I saw Russell take the first wedge out of an oak. He circled the trunk, making more cuts, gauging where he wanted it to land. He moved quickly, using his legs to push the blade hard into the wood. I watched how big it was, how he stepped back and stood still, how all of it moved very slowly before it started to fall.

—

Dylan Nice is in his final year at the University of Iowa’s Nonfiction Writing Program. He is working on a memoir-in-stories about his complicated childhood in the Allegheny Mountains. His work has appeared in NOON, Unsaid, Hobart, Quick Fiction, and Gigantic.

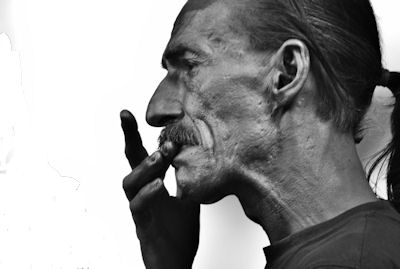

Photo by Dinty W. Moore

1 comment

Edvige Giunta says:

Feb 20, 2023

This is such a fabulous piece. I love the line ” It purred some”–almost an afterthought and yet so essential.