Ronnie Thomley banged on our door early one morning. He runs heavy machinery for Willie Thrift, the pond man.

Ronnie Thomley banged on our door early one morning. He runs heavy machinery for Willie Thrift, the pond man.

He showed up at our place in the pine woods of panhandle Florida driving a compact air-conditioned tractor equipped with a front-loaded rotary cutter. Ronnie’s boss had sent him over to clear out some of the thick yaupon and gall berry bushes around the house to give our longleaf pines a fighting chance.

Ronnie’s longish hair stuck out from beneath the ubiquitous cap of the workingman, his dirty blonde mustache shot through with gray. A potent mix of tobacco, diesel fuel and yesterday’s work clothes entered the house fast as a stray cat when I opened the door. He politely turned down the offer of coffee. Ronnie was here to work.

Ronnie ran that Cat for five hours. He tried his best to lift the blades when he saw a pine seedling, and saved any good hardwoods, too. Around 11:30, he stopped the giant machine for a smoke and was walking and talking with my husband, Buck, when I came around.

Ronnie was telling a story about how he and his family used to live in a small cement block house at the end of the power line. Their home was a perennial target for vicious lightning strikes.

“That lightning would make the whole house buzz and the light bulbs flicker. It would crackle all about. I would grab my two little girls and tell them to go, right now, and get under the bed. We would all just shake.”

The conversation turned to deer. Ronnie lives even further out in the country than we do. About thirteen years ago, he was driving on a back road. Some guys were stopped where one of them had hit a doe with his pick-up truck. He stopped and went over to the scene. The doe was killed in the accident. As the men were standing around talking, Ronnie heard a weak bleating sound.

“I went to look, and there was this tiny, baby deer, with the cord still attached. I felt so sorry for it; I didn’t know what to do.”

He took the baby in his arms and brought it home. There, he raised the doe, feeding her with a bottle. He made a bed for her in a box on the floor beside his own bed.

The doe still stays in a fenced area by Ronnie’s house. Each year in late January, he opens the gate. The doe goes out for a week or so, and then comes back in to his shelter. Each year, she gives birth to twins. She wears a bell so that other humans who might see her will realize she is not wild.

“Most wild deer,” he explained, “they don’t live to be no older than twelve. I’m hoping she’ll make it to sixteen.”

Ronnie feeds the old doe slices of sweet potato by hand every day.

—

Elizabeth Westmark‘s essays have appeared in The Emerald Coast Review XIV, Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, Muscadine Lines: A Southern Journal, and the anthology Digital Dish: Five Seasons of the Freshest Recipes and Writing from Food Blogs Around the World. The former businesswoman blogs regularly on her website. She lives at her home, the Sanctuary at Longleaf Preserve, with her husband and chocolate lab.

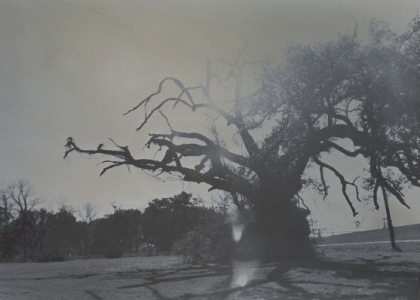

photo by Kristin Fouquet