Choosing a booth, I usher my two boys into their seats. They bounce and squawk like tiny grackles, unable to settle. Happy Meals in Utah no longer come in the brightly colored cardboard boxes of my childhood with golden-arched handles and smiling Grimaces. I pull their meatless cheeseburgers from a non-descript sack, split the dry apple slices and fries, uncap their milk.

Choosing a booth, I usher my two boys into their seats. They bounce and squawk like tiny grackles, unable to settle. Happy Meals in Utah no longer come in the brightly colored cardboard boxes of my childhood with golden-arched handles and smiling Grimaces. I pull their meatless cheeseburgers from a non-descript sack, split the dry apple slices and fries, uncap their milk.

“Simmer down,” I say. “Eat your food.”

Kellen, who sits beside me, his legs barely reaching the end of the bench seat, searches for his pickle, while Aidan sits across. In the temporary hush, I poke at my refrigerated salad.

*

“You look good.”

“I’ve been working out six hours a day, man, until this week when I got kicked out. Down in Vegas, there’s gonna be a cage fight. I’m gonna be on Pay Per View. Pay. Per. View.”

I imagine the speaker, who stands at the booth behind me, stabbing the air for emphasis.

“It’s some serious shit. I’m 155, but I got to get to 160 by next week.”

*

Outside, people line the street waiting for the Fourth of July Parade to begin. Camp chairs and blankets litter the park strip. Whole families perch on tail gates of F-150s.

“We need to hurry up,” I say, dribbling fat-free balsamic on colorless greens.

*

“So is this the newest?”

“Yeah. Four now but Jerry wants more.”

“No way.” Laughter.

“What’s his name?”

“Angel.”

“Does he have a middle name?”

“No,” she sighs; regret rides air-conditioned currents and settles on my shoulders.

*

”She’s looking at me,” says Kellen. “I don’t want her looking at me.”

When I turn in my seat to see who has caught my son’s attention, I see the Latino family, a mother and her four kids, the cage fighter standing, his thin white tank stretched tight across his chest.

“She can look. She’s not hurting you.”

The little girl with hair falling in her face slides back down the booth. Her hands grip the top, ten brown fingers clamped on the ledge.

*

“You working?”

“No.”

“What about the nurse thing?”

“They found out about my felony. Even to be a CNA you can’t have one.”

“No shit. When did you get your felony?”

“2006.”

“What for?”

“Stealing.”

“Man, that’s it, man. Drug dealing and battery are only misdemeanors, but stealing is a felony. Can you get it expunged?”

“I tried.”

*

Aidan has grown quiet. When I follow his gaze behind me, I see the mounted television.

“Stop watching, Aidan.”

“It’s football.”

I turn again. “It’s baseball and stop watching. I want your eyes looking in another direction.”

It occurs to me that my son should know the difference between baseball and football, but he’s never seen either on television, never been to a game.

*

“How’s your dad?”

“Oh man, he got stabbed down in Mexico. He was at some bar and talked to this woman. He didn’t know she had a man. He’s OK now, but he can’t get a job.”

Angel’s mother murmurs understanding before the cage fighter continues. “So where’s Jerry, down state?”

“Nah, the jail here.”

The cage fighter continues. “You should go to Texas, man, it is recession-proof. They got so many jobs in Texas.”

“Really.”

“Yeah, so many jobs, except, you know, it’s a three strike state.”

The table falls quiet, the four kids not making a sound. Then Angel toddles toward a display of model cars.

*

“I like the convertible,” Kellen says, looking at the same display.

“Me too,” says Aidan.

“Come back and eat your dinner. We need to get home. Drink your milk. It’s your protein.”

Kellen refuses the apple slice.

“It’s a green apple. You like the green ones.”

I pile trash on a brown plastic tray and, to get my sons moving, bribe them with their Happy Meal toys, a dinosaur from a movie I will never let them watch.

When I stand, I glance at the booth behind me. The woman, younger than I by a decade, wears a short skirt and brown cami. Her older son plays video games, while Angel bangs on the display case. I nod at the woman as I pass, slow as if to say something, then turn and locate the trash.

*

Outside, summer beats down. The bystanders along Main Street wave flags on cheap sticks, sunlight bleaching the thin fabric. I can hear the approach of the marching band; the bass drum discharges in my chest.

Jennifer Sinor is the author of The Extraordinary Work of Ordinary Writing. Her essays have appeared in the American Scholar, Fourth Genre, Ecotone, Utne, and elsewhere. An associate professor of English, she teaches creative writing at Utah State University.

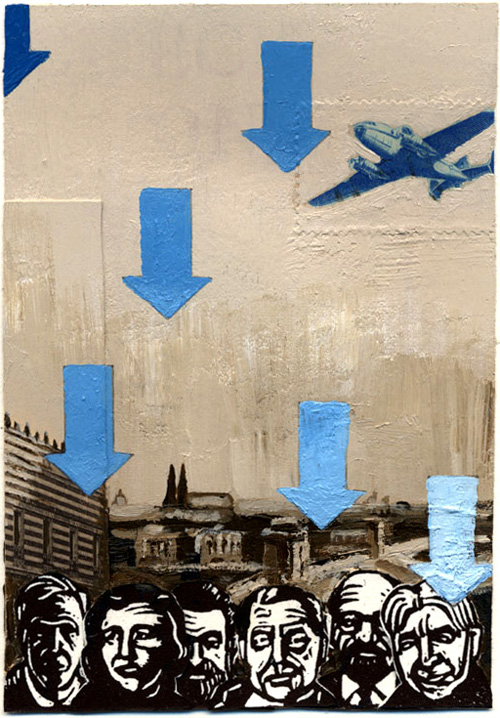

Illustration by Marc Snyder

1 comment

Fiasco says:

Aug 22, 2012

Bravo!