“We was out shootin’ rabbits and Raymond was there just a bitty ahead of me. We both saw that dang bunny at the same time. Onlys when he pulled his trigger he stood up. And when I pulls my trigger, there’s Ray’s head, affront of me.”

His brothers carried him to the closest neighbors. Twenty-one-years-old and looking like dying was the next thing on what was left of his mind. Grandma turned fifty that year. She had a farm crew to feed and a five year old boy—my daddy—underfoot.

Raymond laid there on that couch and lived even after the doctor came and told them to prepare for the worst. And he kept on living. His brothers came and carried him back to home.

There’s things you don’t know, like how Grandma potty trained him, spoon fed him, crawled him, and walked him back to life. My daddy was just starting to read the year after Raymond’s accident. Raymond, learning his reading the second time around, hid a first grade reader under his mattress. A twenty-two-year-old man he was. My daddy saw him hiding it and went to tattle. “Ray’s got suspicious materials under his mattress, Ma.”

As a grown man, Uncle Raymond said his head hurt when it got down chilly—twenty below and the splinters of that bullet twinged in his scalp. Maybe they was good for him, livin’ to be ninety-three-years-old like he did.

There’s things you only know pieces and part of. My uncle’s whole life is just a few snippets of information to me, like that hat he always wore in winter. But those snatches daydreamed inside of me till I could see that lanky boy-man bleeding onto the Stanley’s couch, and later him a crawlin’ over to the dinner table with the boys just in from the field and Grandma having to help him hold his spoon. It’s the kind of story you just have to think about when it’s eleven o’clock at night and the owl’s hooting outside your window and you fall asleep staring at the stars your chin cold on the window sill.

There’s things that are a mystery. Uncle John’s the one I know least.

“John was a marine on Wake Island,” my daddy told me. “That’s where he picked up meningitis. Had a 104 degree fever so they put him in isolation, in a cave with some bottled water and some sliced up bread. Then he was forgot. He got long hair, filthy dirty, and bone skinny by the time he was discovered. He was such a mess they didn’t know what to do with him. Sent him off to a hospital in Honolulu. The nurse there gave him three baths just to see what was underneath. Can you imagine how dirty that tub must have been?”

John went back to Wake—like an apparition—and stayed the war out. Daddy tells me that story each time John doesn’t come home to a family reunion. My daddy’s stories lived in me back then till even the ring around the bathtub was grimy with possibilities.

There’s things I will never know. The last time I saw my daddy—with his only surviving brother—they were standing side by side at Forrest’s grave, taps floating across the prairie and my daddy throwing a handful of black soil into that dirt dug pit, covering up stories that was already hid.

Forrest, a supply sergeant pushing from France into Germany, drove deliveries out to units on the front, in the pitch-dark of night, blackouts being a way of life and you weren’t always so sure which side of the line you were on. He never talked about the war. He came home and raised wheat. And he raised a parcel of sons and kittens, with a few heifers thrown in for luck. A war memory buried deep and sharp surfaced once that I heard tell of: when his only grandson was accidentally killed—at the age of seven—Forrest stood beside that small white coffin and whispered, “At least this one won’t have to go to war.”

There’s only so much the human brain can hold onto: the memory shards, the unsolved mysteries, the patter that hints at more than it can tell. There’s things strange, unbelievable, and hidden. They are in themselves nothing. But I still sit, chin on window, looking up at those self-same stars wondering about those lives, gone before, gone buried.

Jill Noel Kandel grew up in North Dakota listening to prairie stories. She has lived in Zambia, Indonesia, England, and in her husband’s native Netherlands. After working abroad for ten years she returned to the U.S. and currently lives with her husband and children in Minnesota. She has essays forthcoming in Apalachee Review and in Image: A Journal of Arts and Religion. Jill won the Carol Bly Creative Nonfiction Award from Bemidji State University and has been published in Minnesota Literature, Relief: A Quarterly Christian Expression, and in Dust & Fire. She has a BS, RN degree which she seldom uses since creative nonfiction has devoured her life.

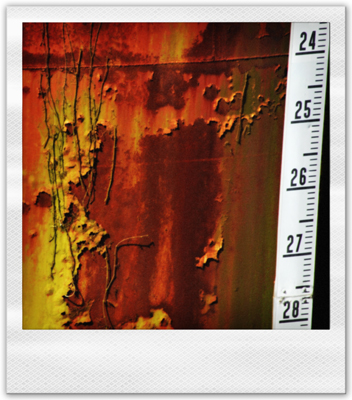

photo by Leslie Miller