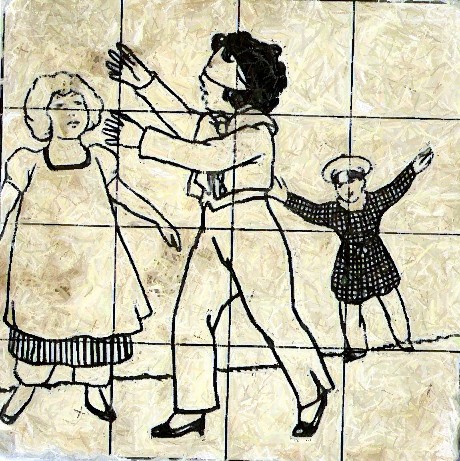

When Sherri Luna rammed Jerry Kruger’s crew cut head into the handball court wall at Kester Avenue Elementary School on February 15, 1964, I knew she loved him, a swirling, butch, embarrassed sort of love that denied itself even as it was expressed. She loved him the way a 9-year-old, beefy-ankled, white-socked, scuffed-up saddle-shoed, Valley girl chicana loves a drawly, red-necked, red-haired, red-freckled, cracker son of a Pentecostal preacher from Oklahoma who wouldn’t let his kid slow dance in Miss Arlington’s A4 class, not because Miss Arlington was a wafer-thin woman with a 2-foot-high beehive hairdo that made her look like an alien from some planet of white-porcelain doll people with blood-red lips and fingernails long and sharp as steak knives, but because Jerry’s preacher pa didn’t believe 9-year-olds, much less anybody, should be cradling one another’s bodies in their arms and breathing softly on their necks as they swayed to music. Nosiree, Sherri Luna didn’t love Jerry that way, the slow dance, fandango way, where holding someone close is as sweet and natural as lying on your back in the back yard watching the clouds and letting the sunlight kiss your cheek, but she loved him just the same. I knew it when I first saw her rub her body up against Jerry’s blue jeans as she slugged him in the arm by the water fountain the first day he came to class that winter. Plus, she didn’t want to slow dance, not because she didn’t believe in it, but because she was constitutionally against any request that curled out of Miss Arlington’s pouty lips.

“Just do it, honey.”

“No.”

“Please?”

“No, I said!”

So, “Ka-Chunk,” went Jerry’s head, cradled in Sherri’s gentle headlock when Miss Arlington was putting a scratchy waltz on the mono record player that Ricky LaConte had lugged out onto the playground after lunch. Ricky, a fat kid who liked to have us punch his stomach in the boys’ room until his bubbly flesh was filled with blotches like lesions, liked to do such favors, his arm shooting up like a rocket ship out of its socket every time Miss Arlington asked with those pouty lips just who would like to do this or that for her. And that’s a sort of love, too, don’t get me wrong, only it wasn’t Sherri Luna’s sort of love. She needed to touch the someone she loved, even if she didn’t understand what the yearning in her heart was asking her 9-year-old body to do.

So, “Ka-Chunk.”

I was breathing my face into Melinda Coates’ blond ringlets, getting hairs twisted in my glasses’ hinges and imagining myself in heaven and then feeling embarrassed for even thinking such a slack-brained thing as that when I heard it.

“Ka-Chunk,” echoing into the mauve plastic handball court wall that rose out of the blacktop playground surrounded by bungalows, chain-link fence, and honeysuckle rustling in the winter breeze like our breaths on one another’s necks as we danced.

“Ka-Chunk.”

“That was fun,” Jerry laughed. “Do it again,” with again drawled out so long, so slow, that it slobbered and dribbled out of his mouth into a dopey-grinned, three-syllabled, shrieky a-gaaa-in.

“Do it a-gaaa-in.”

Poor Ricky. He was right next to me, swaying sort of sad-like, out of time and out of step with Louise Dolan. He wanted to be in that headlock, too, I guess. Maybe he thought that the bumps on his forehead would go with the blotches on his stomach. I don’t know, but I know this. Sheri would have none of him. Ricky wasn’t Jerry in any way, shape, or form, and Sherri Luna loved Jerry. That was that, end of the story. We were dancing that Strauss waltz you hear in 2001 when the ship docks with the space station, and I swear I saw her gently bend over as pretty as you please and nibble out a tongue-licked hickey on that sun-burnt, freckly red neck of his when she thought no one was looking. We stared and stared. Not even the creamy touch of Melinda Coates could keep me from it. No one in Miss Arlington’s A4 class in 1964 had ever seen such a thing.

And then she counted to three. And then she did it again.

And then she did it again. And I swear she didn’t miss a beat, not a one, not a single one.

Stuart Lishan’s work has appeared in Kenyon Review, Arts & Letters, Bellingham Review, Antioch Review, New England Review, In Posse Review, Chicago Review, The Journal and other literary magazines. Body Tapestries, a chapbook of poetry, appeared in the electronic journal Mudlark in 2001. He is currently finishing up a novel, Lightseed, and working on a work of creative nonfiction entitled Winter Counts. He is an associate professor of English at The Ohio State University.